Recreating a Lost Yiddish Database

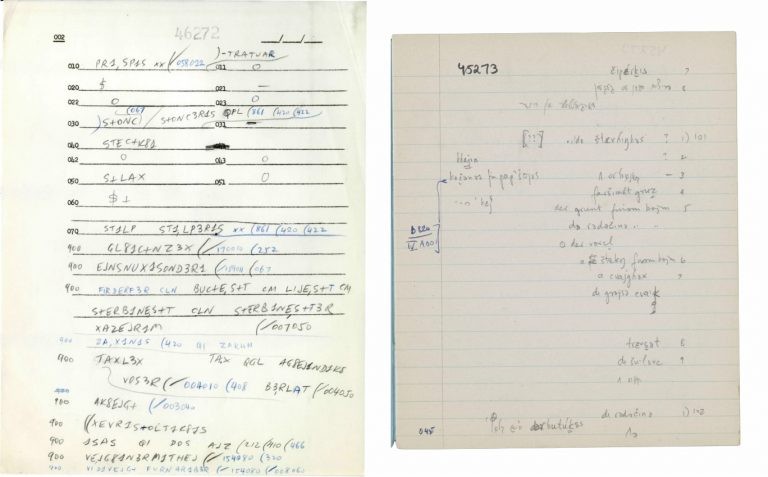

Examples of original, handwritten questionnaires from field interviews with Yiddish-speaking informants, with linguistic field notes in English, Yiddish, and a special linguistic notation system developed for the project by the Columbia Department of Linguistics.

Examples of original, handwritten questionnaires from field interviews with Yiddish-speaking informants, with linguistic field notes in English, Yiddish, and a special linguistic notation system developed for the project by the Columbia Department of Linguistics.

By Michelle Chesner and Janet Gertz

Last year, a Yiddish dialectology scholar contacted Michelle Chesner, Columbia’s Norman E. Alexander Librarian for Jewish Studies, about access to an archive in Columbia’s collection called the Language and Culture Archive of Ashkenazic Jewry. Lea Schaefer, then a Ph.D. candidate in Jewish Studies at the University of Düsseldorf, was beginning work on her Syntax of Eastern Yiddish Dialects (SEYD), a project to digitally map the dialectic variation that can be found in Western and older - largely lost - stages of Yiddish.

An extraordinary resource for research in Yiddish studies, the archive Schaefer sought to map consists of over 600 field interviews recorded between 1959 and 1972 with Yiddish-speaking informants conducted by Columbia University’s Department of Linguistics, who donated the archive to Columbia Libraries in 1995. It was a comparative study of the linguistic diversity of pre-World War II Yiddish in Central and Eastern Europe. Because of the destruction of older Yiddish dialect areas following the Holocaust, the interview project was an imperative effort to collect data from survivors in the United States, Israel, Canada, Mexico, and the Alsace.

“The goal was to trace dialectical differences in Yiddish, based on geographical location,” said Chesner. “They asked subjects questions around basic topics, but they were really listening for glottal stops, or answers to very technical linguistic questions. They also explored different terms that were being used, so it was almost a parallel to the Yiddish dictionary, in a way, of all the varieties of spoken Yiddish.”

Chesner noted that more than 100 authored works, including books and articles, have utilized the archive for research, but the physical collection is enormous and unwieldy for general scholarly use. The 600 interviews are between two-and-a-half and 16 hours each, which makes finding specific types of content extremely labor-intensive, especially since the original database of computer-read punch card data was not preserved. Prompted by requests like Schaefer’s to use the archive in new ways, and the importance of preserving an endangered linguistic and cultural legacy, the Libraries embarked on a process to preserve, digitize, and make more easily accessible the interviews and accompanying documents.

“The Language and Culture Archive of Ashkenazic Jewry is the voice of a vanished Eastern European Jewish past, the tale of a vibrant culture made available in recordings and maps,” said Jeremy Dauber, Atran Professor of Yiddish Language, Literature, and Culture. “It’s irreplaceable."

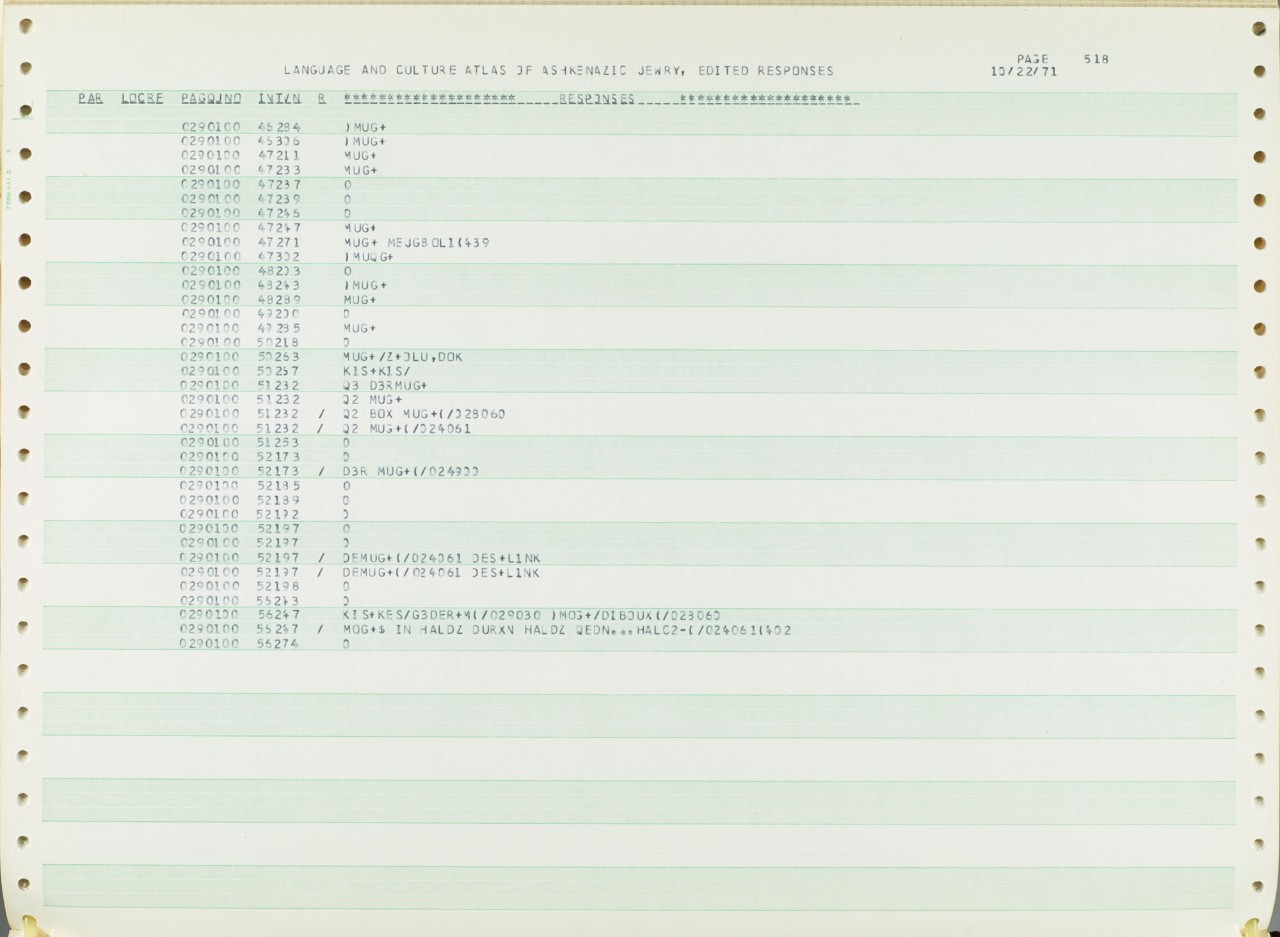

The interviews were collected from people who originally lived in 603 different locations in Central and Eastern Europe to create a sample that reflected the distribution of the Yiddish-speaking population on the eve of World War II. In all, the project produced 5,755 hours of audiotaped sessions with the native speakers and more than 100,000 pages of questionnaires. The documents are covered with hand-written linguistic field notes that were taken during the interviews in a mix of English, Yiddish, and a linguistic notation system developed for the project which uses only characters that computers of the day could handle. No verbatim transcriptions of the interviews were ever made.

In the 1990s, the Libraries digitized the audio from the project, in conjunction with Evidence of Yiddish Documented in European Societies (EYDES), a project of the German Förderverein für Jiddische Sprache und Kultur. The EYDES site provides access to the audio in various ways (including a downloadable repository), and the members of EYDES have transcribed a number of the interviews for scholarly use. But the paper transcriptions of the original data had remained in their numerous boxes for decades.

“The archive presented an interesting preservation challenge, since the original researchers created not only the audiotapes and large quantities of paper documents, but also computer data that were not preserved,” said Janet Gertz, Director for Preservation and Digital Conversion at the Libraries. “Instead, we have printouts of that data on green-and-white striped pin-fed paper, which is what we used to recreate the original database.”

The two-year preservation and digitization project, funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, digitized approximately 140,000 pages of interview documents, carried out optical character recognition and mark-up of the printed responses to enable their content to be searched and manipulated, and made all of the digitized content freely available to scholars through the Digital Library Collections at the Libraries. Additional work allowed for complete reprocessing of the full archive for scholarly use. This source for historical, literary, and anthropological research, for the study of languages in contact, and for the evolution and differentiation of language communities, is now available to a worldwide community of scholars.

“Bringing the archive into the digital environment exponentially increases its value to historians of Jewish studies and European history, linguists, anthropologists, and students and teachers of Yiddish,” said Chesner. “The availability of this data will greatly facilitate the online work of scholars to continue and enhance the important mapping work begun in the first three volumes of the printed Language and Culture Atlas of Ashkenazic Jewry, which were published by Niemeyer in 1992-2000.”

Following preservation and digitization, the Libraries launched a dedicated website for the digitized data of the Language and Culture Archive of Ashkenazic Jewry, which more publicly sheds light on language, ethnography, literature, folklore and music, anthropology, linguistics, Germanic and Slavic studies, and aspects of Central and East European history. Eventually, the Libraries will link the written content to the audio recordings of the interviews (digitized in an earlier series of projects) and make the entire audio and written corpus available to students and scholars in an integrated form.

As part of the launch of the project, an exhibition called “Yiddish at Columbia,” which focused on the long and famed history of the Yiddish department at Columbia, as well as the deep Yiddish collections in the collection of the Rare Book & Manuscript Library, was held in the Chang Gallery at Butler Library from April to June of 2018. A digital version of the exhibition is currently underway and is expected to be live by the summer of 2019.