Emilie Grace Briggs

There are no surviving photos that positively identify Emilie Grace Briggs (1867-1944), daughter of Charles Augustus Briggs and Julia Valentine Briggs. (She is thought to be furthest or 2nd to the right in the newspaper drawing shown at left.) The first woman to graduate from Union Theological Seminary (1897) just one year after women were allowed to 'visit' classes, she devoted her life to biblical exegesis and teaching, care for her father's estate (including his unpublished works), and her ongoing study of 'women as deacons.'

Although she was a Ph.D. student at Union and finished her requirements, she never received her doctoral degree due to her inability to get her dissertation published, a special proviso made for her by the graduate faculty in 1913, two months following her father's death. Briggs was additionally the second woman elected to the Society for Biblical Literature and Exegesis, in the same year as her graduation from Union. She never married, and died in June, 1944.

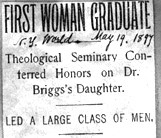

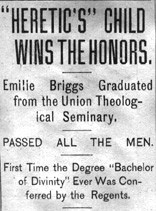

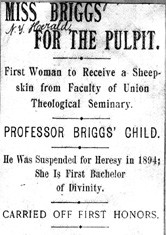

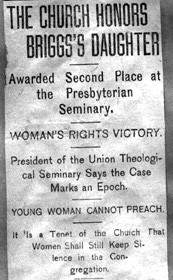

"Heretic's Child"

Shown here are several headlines from articles detailing Emilie Grace Briggs's graduation from Union Seminary in 1897, copied from leaflets in her mother's scrapbooks (one was kept for each child). Briggs was not only the first woman to earn a degree from Union—she was the first person to earn a B.D. degree the first year it was awarded, and due to her high academic standing she was the first person to walk across the stage in the procession and conferral of degrees at that commencement. These articles were kept in a scrapbook by her mother, Julia Valentine Briggs. There exists, though, no record of her having received a diploma. Her alumna file, additionally, is scant. Six other women attended classes with Emilie Grace Briggs, but no record exists of their having finished their requirements or graduated. Their names are also unknown.

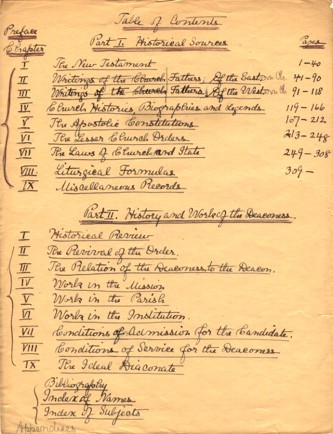

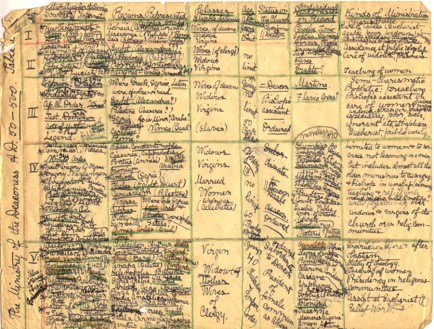

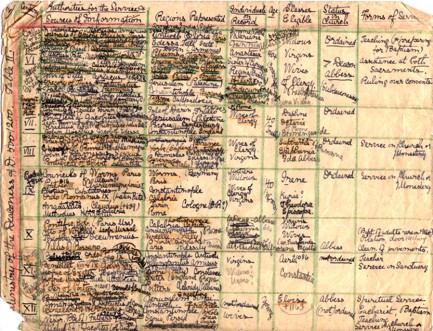

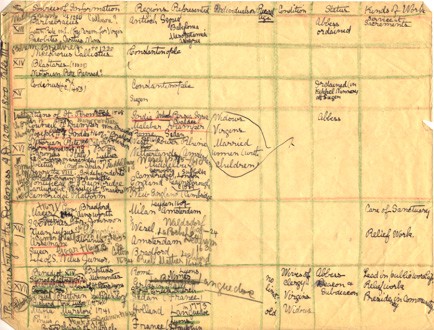

Table of Contents, "The Deaconess"

Table of Contents, "The Deaconess"

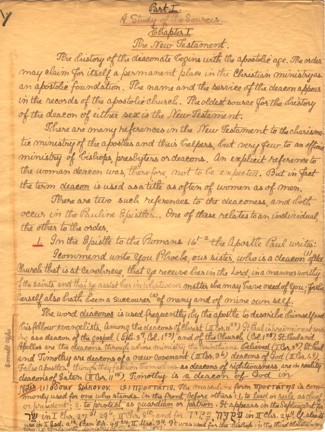

First Page, "The Deaconess"

First Page, "The Deaconess"

Skilled, colorful exegesis

Following her graduation, Briggs continued to take courses at Union with her father, Charles A. Briggs. She also took a job teaching New Testament, Greek, and Hebrew at the New York School for Deaconesses. Her real passion, though, was for textual exegesis. She filled numerous notebooks of textual study, filled with word studies and alternate spellings/sayings, as well as historical interpretations. She additionally kept clippings with biblical references or poetry in separate books with daily prayers and family birthdays; she exegeted her clippings as well. Briggs knew at least six languages—English, German, French, Greek, Hebrew, and Latin—and could move between them with relative ease. Much of her work also is an attempt to continue her father's exegesis and commentary on Lamentations and her brother Alanson's work in Song of Songs.

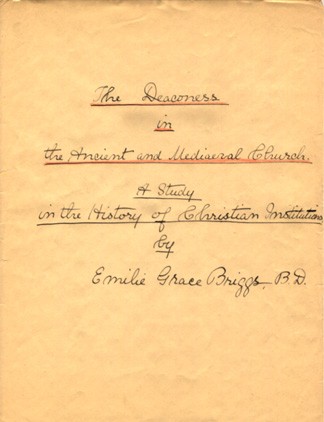

An unpublished masterpiece

At right is shown the cover of Briggs's unpublished doctoral dissertation, "The Deaconess in the Ancient and Mediaeval Church: A Study in the History of Christian Institutions." This work, which is handwritten and spans over 700 pages, was under constant revision and preparation for publication from 1912 through at least 1925. Briggs made several title pages for it, giving the book such alternate names as "The Woman Deacon in History" and "A History of Deaconesses in the Christian Tradition." She also included several dedication pages—two to her sister Agnes, "the ideal deaconess," and one to her father. The structure of the book was a matter of question as well; she had made several drafts of table of contents pages, changed her chapter headings significantly, and pasted in clippings with different headings, more footnotes, or language/character corrections.

"The Deaconess..." is a thorough examination of women's roles in ministry and church leadership from the time of the Jesus movement to the medieval period. It is part word study, part exegesis, part commentary, and ends with a prophetic call to the contemporary church to live up to its promise of women's full participation—using the 'deaconess' as example. Briggs is careful to note that even the word 'deaconess' is misunderstood and has been assigned to women, as the earliest women deacons were called just that—'deacons,' same as men.

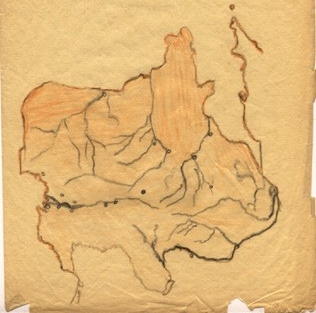

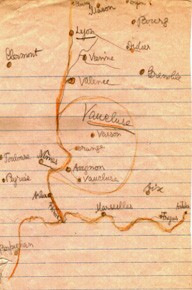

Below are three tables and hand-drawn maps of deaconess locations, which are inserts in Briggs's dissertation. The tables serve as a database or chart of sorts, detailing when, where, how, in what context, and what the status of woman deacons was when they were mentioned in texts ranging in time period from the New Testament to medieval writings. The maps are charts of the geography of deaconesses during an unspecified time period.

Hand-Drawn Tables of Deaconesses

Hand-Drawn Maps

Publish or Perish?

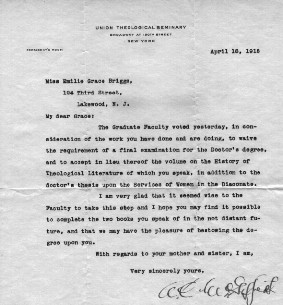

Professor Briggs's death in 1913 from a long illness left the close-knit family devastated. Emilie, the most academically competent, closest in training, and interested in continuing her father's work, was charged with the prospect of finishing his undone research and seeing his unfinished projects to publication. At the same time, she was working toward her own Ph.D. degree at Union and was completing the requirements toward that goal. The task, priority, and expectation of publishing her late father's work caused her to postpone her own research. Emilie, while working for several years on her father's books, had all but ceased her doctoral research and apparently had assumed that she was no longer a degree candidate. Correspondence between she and the graduate faculty during 1917-18 reveals that they had voted that they would award her a Ph.D. degree and would even waive the remaining requirements—the only stipulation being that she publish her dissertation as a book.

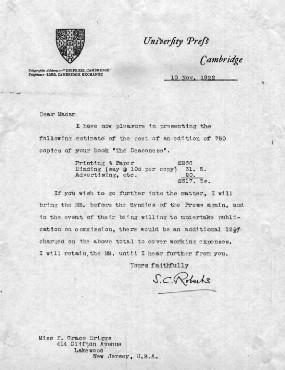

Briggs began corresponding with the same major publishing houses that published her father's works. She expressed caution and a desire to both finish her own degree and the work of her father, but she wanted to know if it would be worthwhile to attempt to publish her own dissertation. After being assured that her work would be a most welcome addition by most publishing houses, she set out to make her revisions and sent her manuscript to publisher after publisher, only to be met with unnecessary obstacles—such as the recommendation that she pay for the publishing herself, that she take out some of the foreign language references as they would be expensive to print, and that she reconsider her subject matter. Publishers also wrote to her and notified her that although 'experts' had scrutinized her manuscript, they could confirm a high level of scholarship but could not guarantee that her book would sell, because 'no one is interested in deaconesses.' Harvard University Press called her manuscript "interesting and imaginative, but unsellable." Cambridge University Press, which told her that publishing religious books was becoming unfashionable and quite expensive when she sent her manuscript to them, immediately made an offer when she sent her father's material later. Briggs withdrew her manuscript from every publisher. It remains unpublished—and she never received her doctorate.