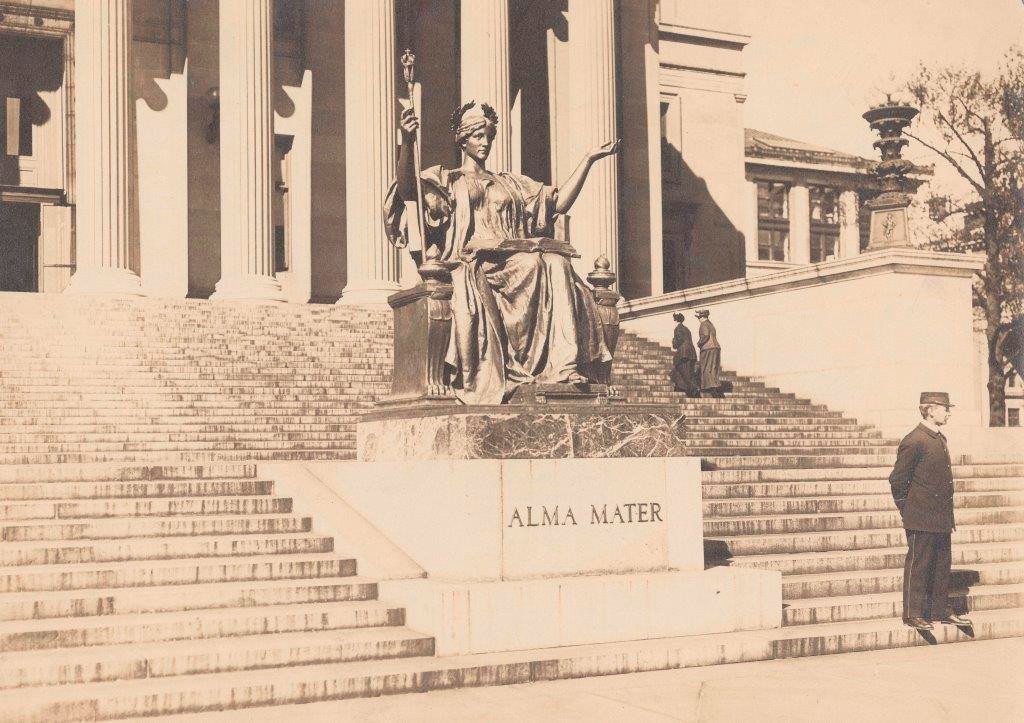

Alma Mater: Lore and Pranks

Throughout the century, the Alma Mater statue witnessed change and conflict on Columbia’s campus; but she also helped create new traditions that fostered a sense of community among Columbians.

Almost immediately, Alma Mater became known for the tiny, hidden owl buried in the folds of her skirts, and throughout the next several decades, Columbia students and faculty debated its significance. What did the owl signify? And why did French include it in his design? Many College men (until 1983, the College admitted only men) joked that any student who found French’s owl would marry a Barnard girl. Still others claimed that the first member of the College’s freshman class to find the owl would be valedictorian four years later.

Others offered more historical explanations. Dwight C. Miner, professor of History at Columbia during the 1950s, maintained that French was a member of the Psi Upsilon fraternity. The professor argued that the owl, the fraternity’s symbol, was a nod of loyalty to the sculptor’s own Alma Mater and to his fraternity. [1]

[1]

In October 1953, French’s daughter Margaret French Cresson, herself a sculptor, addressed the speculation about the owl’s meaning in a letter to The New York Times in order to clear up “a few little misconceptions” about her father’s intent. “As for the little owl only partially visible in the folds of her college gown, this ‘item of mystery’ represents no fraternity and poses no labyrinthine riddle,” Cresson wrote. “The owl is the age-old symbol of wisdom and was used by the sculptor to convey that interpretation. Possibly [French] was hoping that in pursuit of knowledge youth might indeed find wisdom.” By this time, though, the various theories about Alma Mater’s owl had already become an integral part of Columbia’s lore and traditions. [2]

As the most visible symbol of the school, Alma Mater also found herself the victim of many college pranks. In 1928, the Buildings and Grounds crew discovered that the crown that sat atop the statue’s scepter had disappeared. After the University offered a reward for the crown’s safe return, a young man delivered it to the school, claiming he had found the crown in a restroom and, not recognizing it, kept it until he learned of the reward. A few years later, undergraduates gave the grand dame of Columbia a bright red manicure and pedicure.

Perhaps most daringly, in October 1984, some visiting Cornell students removed Alma Mater’s entire scepter. Missing for almost two months, the scepter showed up on the doorstep of Cornell’s Dean of Students in mid-December, covered in Cornell pennants. The scepter was hand-delivered by a Cornell professor to the Columbia Buildings and Grounds Department the next day. [3]

[1] "Columbia University’s ‘grand old lady’ is 50 years old today," University Symbols: Alma Mater, Historical Subject Files, University Archives, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

[1] "Columbia University’s ‘grand old lady’ is 50 years old today," University Symbols: Alma Mater, Historical Subject Files, University Archives, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

[2] Letter to the editor, New York Times, October 27, 1953, University Symbols: Alma Mater, Historical Subject Files.

[2] Letter to the editor, New York Times, October 27, 1953, University Symbols: Alma Mater, Historical Subject Files.

[3] "Columbia’s Alma Mater Robbed of Crown; Under Canvas Cover She Awaits Its Return," New York Times, August 8, 1928; clipping, “Stolen Crown Restored, Columbia Unveils Her Alma Mater Statue,” New York World, August 24, 1928; "Vicissitudes of City Statues: Jokers and Vandals Find targets Ready to Hand," New York Times Magazine, May 10, 1936; Columbia University press release, "Alma Mater's Scepter is back at Columbia, unharmed" December 19, 1984, University Symbols: Alma Mater, Historical Subject Files.

[3] "Columbia’s Alma Mater Robbed of Crown; Under Canvas Cover She Awaits Its Return," New York Times, August 8, 1928; clipping, “Stolen Crown Restored, Columbia Unveils Her Alma Mater Statue,” New York World, August 24, 1928; "Vicissitudes of City Statues: Jokers and Vandals Find targets Ready to Hand," New York Times Magazine, May 10, 1936; Columbia University press release, "Alma Mater's Scepter is back at Columbia, unharmed" December 19, 1984, University Symbols: Alma Mater, Historical Subject Files.