Alma Mater: In the 20th Century

Over the course of the twentieth century, Columbia’s stately Alma Mater statue became the visual symbol of Columbia University around the world. From her perch on the steps of Low Library, she presided over the tumultuous events occurring on campus throughout the century. Alma Mater was erected less than ten years after Columbia moved up to is Morningside Heights location, and she served as an eyewitness to the campus’s expansion and transformation. Modern buildings rose on either side of her southward-facing throne. In the 1920s, one of Columbia’s most celebrated students, Henry Louis Gehrig, hit home runs far enough to hit Alma Mater, a feat that few other Columbia athletes would match; several decades later, she would see Gehrig’s South Field torn down and replaced by more bucolic lawns and walkways. And she sat sedately as Low Library ceased to be a working library when Butler Library was built in 1934. [1]

- Early History

- Erecting the Statue

- In the 20th Century

- Lore and Pranks

- In the 21st Century

- Bibliography

As Columbia’s campus continued to undergo change, Columbians debated Alma Mater’s appearance as well. Alma Mater’s look was altered a number of times over the twentieth century due to the natural weathering of the elements and to various artificial treatments administered by Columbia’s Buildings and Grounds department. The gold leaf applied to Alma Mater’s bronze finish in 1903 prevented the statue from forming the green patina brought on by extensive exposure to the elements. In June 1950, the campus grounds people removed the last of the flaking gold leaf in order to catalyze Alma Mater’s patina. Their goal was to give the grand figure an older, more weathered appearance.

By 1962, this “look” no longer satisfied the Department of Buildings and Grounds. That summer, an administrator approved a plan to gild the statue with a more modern bronze veneer (Later, no one would take credit for the decision, though Director of Buildings and Grounds William J. Whiteside took much of the heat for the decision.) When the refurbished Alma Mater was unveiled, students, professors, and even University President Grayson Kirk expressed their disapproval, and the Columbia Spectator ran almost daily stories critical of the university bureaucracy’s unwillingness to take responsibility for the gaffe. Soon after the school year began, the bronze paint was removed and Alma Mater’s earlier patina was restored.

For many Columbians, there was more at stake than the bronze finish of the statue. Alma Mater’s appearance represented the chronic identity crisis with which the university grappled throughout the century. Should Columbia emphasize its role as a modern, forward-looking institution that paved the way for other school? Or should she remain true to her history and traditions?

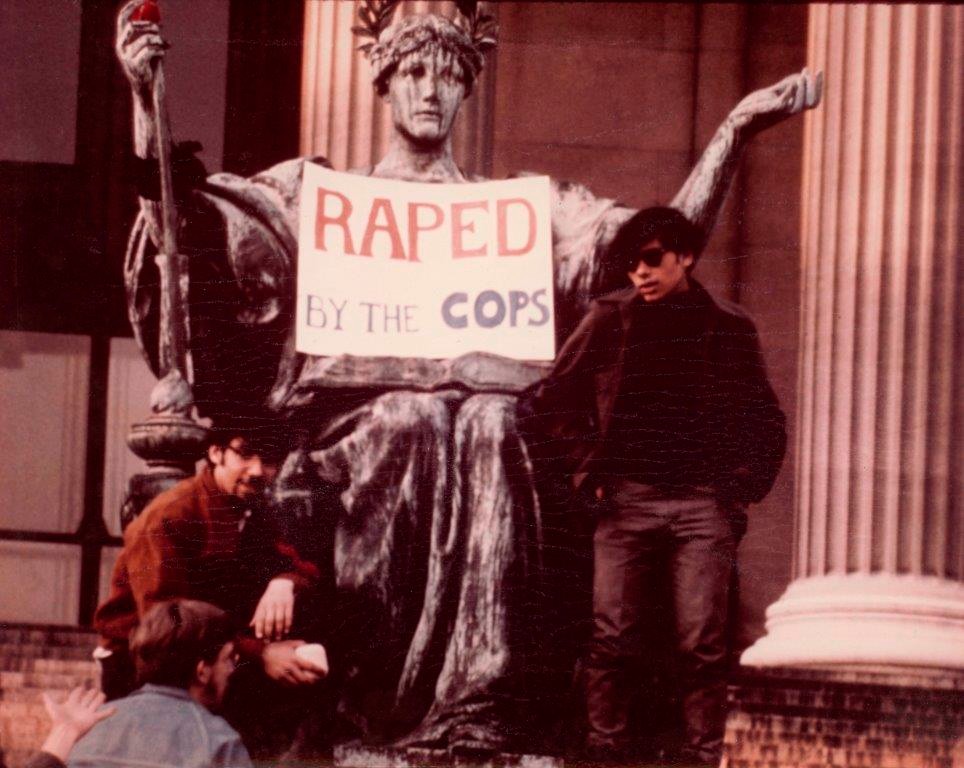

The student body’s protests over Alma Mater’s alterations also reflected a growing activism and anger among Columbia’s undergraduates toward the university bureaucracy. In the late 1960s, Columbia became a center of student political activity and of the antiwar movement. In the spring of 1968, Alma Mater witnessed the student takeover of the Morningside Campus and the subsequent violence that erupted between undergraduates and New York City policemen.

For many of Columbia’s radical students, Alma Mater served as a symbol of the manifold failures of the University’s administration. During the tumultuous spring of 1970, when radical demonstrations broke out on campuses across the country, Alma Mater became a target. Before dawn the morning of May 15, 1970, a bomb planted on Alma Mater exploded and destroyed a portion of her throne. The damage remained for eight years, a visually stunning reminder of the upheaval that took place on the University’s campus in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

In 1978, Columbia announced that Alma Mater would leave the campus for the summer for repair. Her departure marked the first time that Alma Mater left her perch on the Low Library steps since her 1903 unveiling. Instead of quietly placing the university’s grand dame back in her place that fall, the University hosted a solemn public ceremony to welcome the statue back. On September 19, 1978, Alma Mater was brought from a Peekskill, New York foundry to Amsterdam at 119th Street. After she was delivered to campus via Schermerhorn Hall’s freight elevator, where a small flatbed and truck waited to drag her to her to the front of Low Library. A number of students and members of the press watched as university grounds people placed her ceremoniously on her granite pedestal.

“French’s Alma Mater,” The New York Times observed, “has been restored in the spirit of the 1970s.” The quiet return of Columbia’s most visible symbol served as a marked contrast to the passionate and sometimes violent demonstrations seen on campus in the 1960s and early 1970s. The University, moreover, came to a consensus on Alma Mater’s appearance: “The bomb-damaged chair segment has been recast, the cracks of time have been repaired and a ‘new’ patina applied,” the Times reported. “This new-old finish guarantees a blend of maturity and innocence that eluded the 1960s.” [2] Perhaps Alma Mater’s uneventful refurbishment reflected a return to normalcy, perhaps a return to apathy. Regardless, it was clear to all that the tone of the campus had changed significantly since the late 1960s.

[1] Columbia University press release, "Columbia University's 'grand old lady' is 50 years old today," September 23, 1953, University Symbols: Alma Mater, Historical Subject Files, University Archives, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

[1] Columbia University press release, "Columbia University's 'grand old lady' is 50 years old today," September 23, 1953, University Symbols: Alma Mater, Historical Subject Files, University Archives, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

[2] "The Lady on the Pedestal" New York Times, November 14, 1978, University Symbols: Alma Mater, Historical Subject Files.

[2] "The Lady on the Pedestal" New York Times, November 14, 1978, University Symbols: Alma Mater, Historical Subject Files.