Alma Mater: Erecting the Statue

Columbia’s Alma Mater became a much more prominent visual symbol in the early twentieth century, when famed sculptor Daniel Chester French began work on a large bronze statue of the university’s beloved symbol. At the time that French was contracted to build the statue, Columbia was entering into a period of significant growth. In the 1890s, under the leadership of President Seth Low, the university moved from its cramped quarters in midtown Manhattan to the more spacious Morningside Heights location, where the school remains today. Built in 1895, Low Library, with its stunning rotunda, served as the centerpiece of the new, modern campus.

Until recently, most have assumed that Columbia erected the central buildings of the Morningside Campus before any plans for outdoor sculpture had been made. Recently, though, art historian Michael Richman has revised this timeline. Though the Alma Mater statue would not be commissioned until 1900, the chief architect of the Morningside Heights campus, Charles McKim, included a large slab of granite in his 1897 plans for the grand staircase up to Low Library. The granite, Richman tells us, was a placeholder; in McKim’s vision, the Low Library stairs would not be complete without a particularly impressive statue to welcome visitors to the university. [1]

[1]

- Early History

- Erecting the Statue

- In the 20th Century

- Lore and Pranks

- In the 21st Century

- Bibliography

The opportunity to erect such a statue came a few short years after. In late February of 1900, the Trustees of the University received a letter from Harriette Goelet, the widow of a prominent New York lawyer and real estate mogul, offering to present to the University a statue in honor of her late husband. According to her proposal, she envisioned “a bronze statue representing ‘Alma Mater’ to be placed upon the pedestal in front of [Low] Library, bearing the inscription: ‘In Memory of Robert Goelet, Class of 1860.’” The Goelet family offered to bear the cost of the statue up to $25,000. It appears that the Trustees were quite pleased with the Goelets’ offer. At their March 5th meeting, they voted unanimously to accept the Goelets’ gift “with grateful thanks.” [2]

[2]

McKim, like the Trustees, was pleased about the plan for the statue. He would play an important role in the creation of the Alma Mater statue, from its commissioning to its unveiling. After the Trustees sent their letter of approval to the Goelets, McKim recommended the sculptor Daniel Chester French for the job. [3] By 1900, French had made a name for himself as an accomplished artist of outdoor sculpture. He was particularly known for his Minute Man in Concord, Massachusetts and the John Harvard statue on the campus of Harvard University.

[3] By 1900, French had made a name for himself as an accomplished artist of outdoor sculpture. He was particularly known for his Minute Man in Concord, Massachusetts and the John Harvard statue on the campus of Harvard University.

Both French and McKim played important roles in the American Beaux Arts movement at the turn of the century, which sought to highlight architectural design with sculptural art forms. Both found inspiration in the Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago in 1893, whose planners drew on classic European architecture and sculpture yet hoped to recast it in a uniquely American way. French himself designed the sculptural centerpiece of the Exposition, a sixty-five foot statue of a female Republic – a figure that resembled his forthcoming Alma Mater a great deal. [4]

[4]

French spent the summer conceiving and designing Goelet’s statue. By October, he had cast a smaller plaster figure for Goelet, McKim, the Trustees, and the university’s various committees to review. Throughout the fall and the winter of 1900-1901, various university figures dropped by French’s New York studio to judge the mock-up of Alma Mater. McKim himself was pleased with the sculptor’s model. Writing to Mrs. Goelet in December of 1900, the architect tendered his opinion of French’s plan: “I can only say that I was greatly delighted and relieved to find in Mr. French’s creation a figure dignified, classic and stately, studied with fine care and knowledge of detail, yet exhibiting as much perception of the spirit and freedom of the Greek as anything modern can.” On March 4, 1901, on the recommendation of the Committee on Buildings and Grounds and the Committee on Art, the Trustees approved French’s model. Soon after, French and Goelet finalized their contract. French was to be paid $20,000 for the finished statue. The artist and the Trustees expected that Alma Mater would grace the steps of Low Library no later than Commencement, 1902.[ 5]

5]

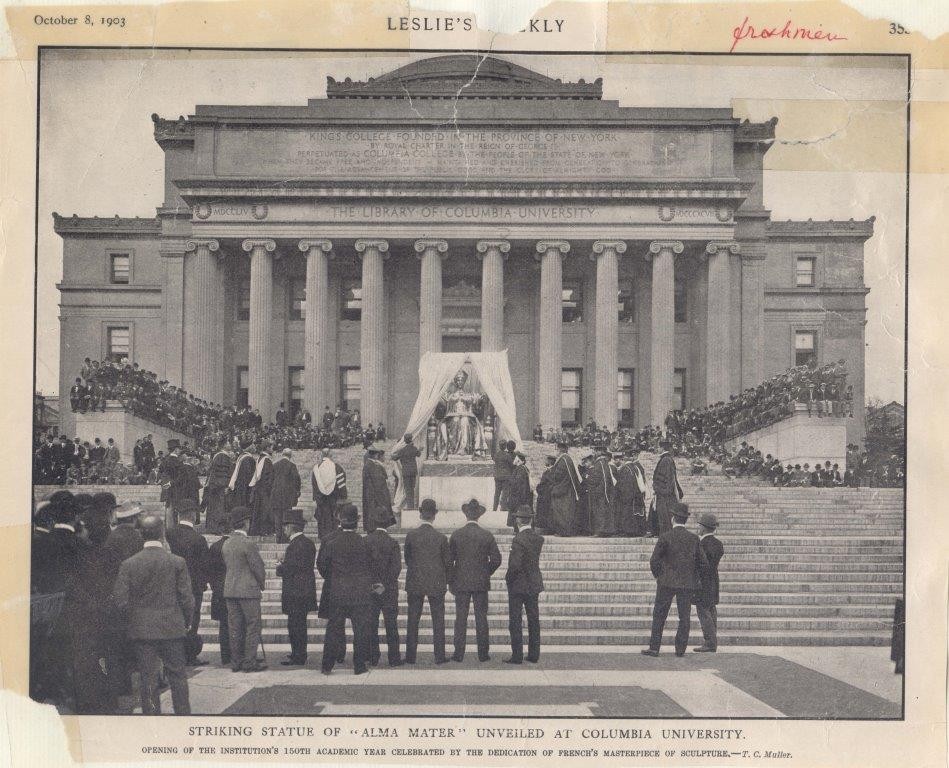

By 1903, the University had a new president, Nicholas Murray Butler – but still no Alma Mater statue. After a plan to unveil the statue at that year’s Commencement went awry, Mrs. Goelet’s lawyer confessed to President Butler that his client “has been quite impatient at the delay of Mr. French in completing the work.” [6] French’s masterpiece was finally erected and introduced to the public on September 23, 1903, the first day of classes for the new school year. The Goelet family did not attend, having departed for Europe for the fall season.

[6] French’s masterpiece was finally erected and introduced to the public on September 23, 1903, the first day of classes for the new school year. The Goelet family did not attend, having departed for Europe for the fall season.

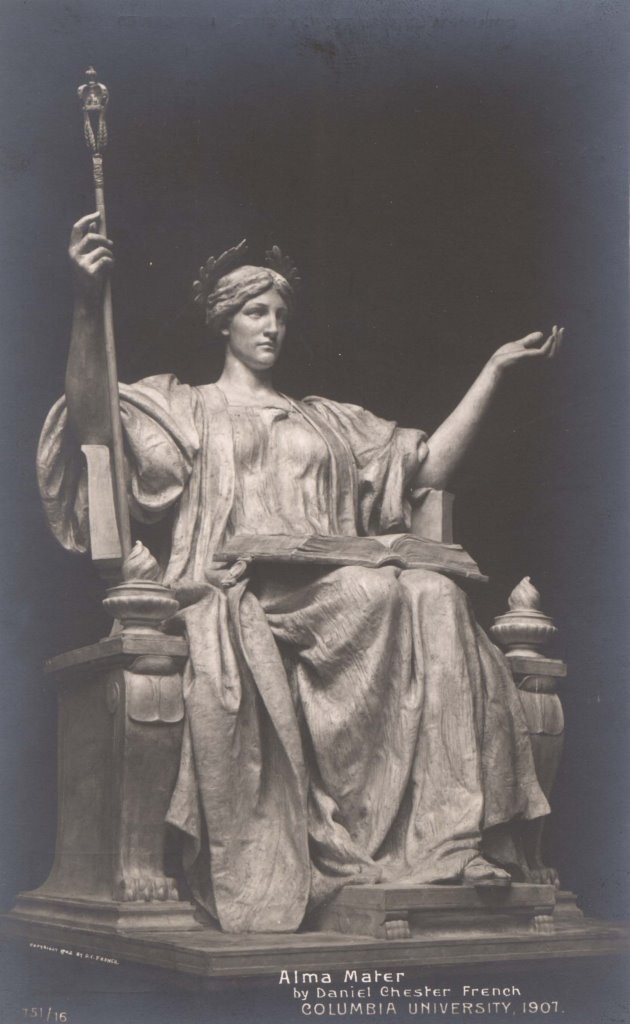

The statue stands 253.8 centimeters, or a little over eight feet tall. Cast in bronze and covered in a gold leaf wash, the statue features a woman seated on a simply adorned but stately throne. In her right hand, Alma Mater holds a scepter of four sprays of wheat, on top of which rests a small version of the original crown of King’s College. Her left arm is outstretched, welcoming visitors and new students to the campus. On Alma Mater’s lap rests a book of learning. As an irreverent detail, French hid a small owl, which represented knowledge and learning, in the folds of her long skirt. Like true knowledge, the hidden owl is well hidden and takes some time to find. [7]

[7]

Despite French’s tardiness, his rendering of Alma Mater was well received by Columbia administrators and students as well as the New York press, though the sculptor was reportedly upset that the statue did not make a bigger splash on New York City. Most who observed the statue found it to be an attractive enough work of art; much later, however, one reporter would refer to French as “one of the dullest men who held a chisel.” Regardless of taste, French’s Alma Mater blended well with the stately Beaux Arts style of the new campus. [8]

[8]

[1] Alma Mater, pamphlet, "Alma Mater at 100: A Reappraisal of a Daniel Chester French Masterpiece," October 17, 2003, University Symbols: Alma Mater, Historical Subject Files, University Archives, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

[1] Alma Mater, pamphlet, "Alma Mater at 100: A Reappraisal of a Daniel Chester French Masterpiece," October 17, 2003, University Symbols: Alma Mater, Historical Subject Files, University Archives, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

[2] Robert Goelet, Historical Biographical Files, University Archives, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York; Trustee Minutes, March 5, 1900, University Symbols: Alma Mater, Historical Subject Files.

[2] Robert Goelet, Historical Biographical Files, University Archives, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York; Trustee Minutes, March 5, 1900, University Symbols: Alma Mater, Historical Subject Files.

[3] Michael Richman, Daniel Chester French: An American Sculptor (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art for the National Trust for Historic Preservation, 1976), 90.

[3] Michael Richman, Daniel Chester French: An American Sculptor (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art for the National Trust for Historic Preservation, 1976), 90.

[4] Columbia University press release, May 17, 1978, University Symbols: Alma Mater, Historical Subject Files; Andrew S. Dolkart, Morningside Heights: A History of its Architecture and Development (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), 134.

[4] Columbia University press release, May 17, 1978, University Symbols: Alma Mater, Historical Subject Files; Andrew S. Dolkart, Morningside Heights: A History of its Architecture and Development (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), 134.

[5] Richman, 90; McKim to Mrs. Goelet, December 11, 1900, Alma Mater Statue, Central Files, University Archives, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

[5] Richman, 90; McKim to Mrs. Goelet, December 11, 1900, Alma Mater Statue, Central Files, University Archives, Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University in the City of New York.

[6] De Witt to President Butler, August 12, 1903, Alma Mater Statue, Central Files.

[6] De Witt to President Butler, August 12, 1903, Alma Mater Statue, Central Files.

[7] Richman, 90; Dolkart, 133.

[7] Richman, 90; Dolkart, 133.

[8] John Tauranac, Elegant New York: The Builders and the Buildings, 1885-1915 (New York: Abbeville Press, 1985), 258; John Russell, "One of the Dullest Men Who Held a Chisel" New York Times, January 2, 1977, Daniel Chester French, Historical Biographical Files.

[8] John Tauranac, Elegant New York: The Builders and the Buildings, 1885-1915 (New York: Abbeville Press, 1985), 258; John Russell, "One of the Dullest Men Who Held a Chisel" New York Times, January 2, 1977, Daniel Chester French, Historical Biographical Files.