Bird Motifs and Pueblo Pottery: Research Report by Michael Gibson-Prugh

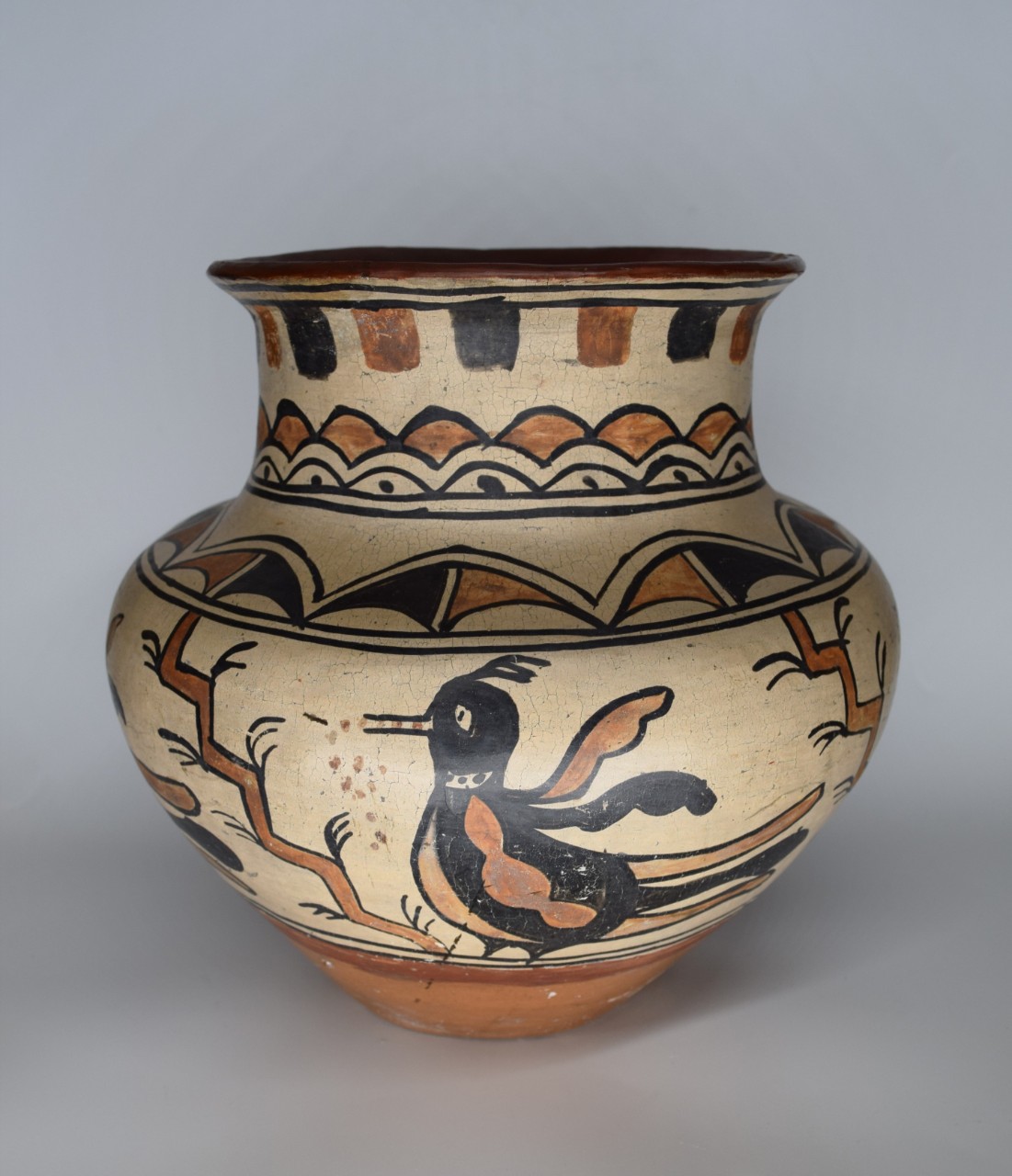

Fig. 1. Unidentified San Ildefonso artist, Pot with flared neck and lip, with bird designs on body, ca. 1905, New Mexico, clay with pigment, H. 9 3/4 x W. 10 3/8 x D. 10 3/8 in. (25 x 26.5 x 27 cm), Art Properties, Avery Library, Columbia University, Gift of Stanley B. and Caroline Stein (1997.08.035).

Fig. 1. Unidentified San Ildefonso artist, Pot with flared neck and lip, with bird designs on body, ca. 1905, New Mexico, clay with pigment, H. 9 3/4 x W. 10 3/8 x D. 10 3/8 in. (25 x 26.5 x 27 cm), Art Properties, Avery Library, Columbia University, Gift of Stanley B. and Caroline Stein (1997.08.035).

In Fall 2022 Art Properties received an award from Columbia University Libraries as part of its Antiracism, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusiveness (ADEI) program. This award made possible the hiring of two Columbia graduate students to study, research, and report on areas of the Native American collection in Art Properties.

Michael Gibson-Prugh, the author of this essay, attended Columbia University and earned his MA in American History and the Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race, with a focus in Native American studies. Michael's report is not intended to be a definitive guide on this topic of Pueblo pottery, but rather demonstrate innovative possibilities when researching Native American objects in Columbia's Art Properties collection. This educational opportunity is particularly important in our efforts toward more transparency and visibility with our Native American collections, and Columbia University Libraries' ongoing commitment to ethical stewardship and fulfillment of our responsibilities to be in compliance with the federal Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA).

Our thanks to Columbia University Libraries and the ADEI Award program for sponsoring these educational opportunities in Art Properties, and to Nancy Rosoff, Andrew M. Mellon Senior Curator, Arts of the Americas, Brooklyn Museum, for her assistance and advice with the students' research.

Bird Motifs and Pueblo Pottery in the Art Properties Collection at Columbia University

Research Report by Michael Gibson-Prugh, Graduate Student Assistant 2022-2023, Art Properties

Native American pottery from the Southwest has become an iconic example of Indigenous art. The creative skills used to make ceramics date back thousands of years. These pieces have shifted from their primary use in daily life for eating and drinking to being created, sold, and purchased as souvenirs or for display in private or public collections. Regardless of their initial use, there is an aesthetic intention and value imparted to these pottery pieces. Southwestern Pueblo pottery's artistic tradition and iconography have significant artistic and cultural meaning. These ceramics are made with clay dug up from the desert of the American Southwest, an arid environment with an extreme climate with a range of temperatures and landscapes. Primarily, the Pueblo people live in scorching and dry areas, with a central need for water. Therefore, the relationships with the land and rain for survival are crucial to the functioning of Indigenous societies and their creation myths and cultural heritage. Ceramics serve as vessels for carrying and containing water in this environment. Therefore, digging the clay, sculpting the pots, and using these items have become a form of sacred importance to these Indigenous communities. For instance, gathering and hand-coiling the clay is itself a ritual (Berlo & Phillips 57). Some Pueblo communities, such as the Zuni and Santa Clara Pueblo, symbolize thunder by rolling earth and clay making. The Acoma people smash or roll clay balls together to show and pray for rain and thunder (Parkman 97).

Fig. 2. Unidentified Hopi artist, Bowl with interior design of a turkey in a landscape, late 19th to early 20th century, Hopi reservation, Arizona, clay with pigment and slip, H. 2 3/4 x Diam. 8 7/16 in. (7 x 21.4 cm), Art Properties, Avery Library, Columbia University, The Bush Collection of Religion and Culture (C00.1483.355).

Fig. 2. Unidentified Hopi artist, Bowl with interior design of a turkey in a landscape, late 19th to early 20th century, Hopi reservation, Arizona, clay with pigment and slip, H. 2 3/4 x Diam. 8 7/16 in. (7 x 21.4 cm), Art Properties, Avery Library, Columbia University, The Bush Collection of Religion and Culture (C00.1483.355).

These associations between ceramics and the natural environment around them extend beyond the materials used to create pots. A formal analysis of the Hopi bowl above demonstrates the connections in the decoration of these ceramic pieces. The above piece was likely made around the beginning of the 20th century. Women primarily formed and made the pots, digging the clay with their families and hand-coiling it into shape, leaving it to bake in the hot desert sun. The visual style of this piece is striking for the white slip background and the incorporation of black and brown colors. The white background with red or black coloring has appeared in Pueblo ceramics for millennia and constitutes a recognizable style. Most Pueblo plates have designs on the inside that the individual eating or drinking from would come face-to-face with throughout their meal. The intricate interior artistry contrasts with the exterior of the plate that remains white, and there are rings, some cut off at the bottom, that encircle the image of a bird in the center. This bird appears to be a turkey, as the feathers have a distinct two-tone appearance at the end, which references their role in the creation myth (Espinosa 87). Turkeys aided Spider-Woman, who, according to the Hopi, gave the gift of weaving to humans and guided them to their homeland (AMNH; Hutchinson; Swan 229-30; Vecsey 76-89). The abstract geometric designs incorporated onto the bird’s stomach are part of a long history of representing the natural world through abstract means. Further, there is floral patterning, precise brushstrokes, and a painted texture resembling feathers at the bottom of the bowl. Even though ancestral Puebloans had close relationships with turkeys for hundreds of years, valuing them for their feathers and use in craft, they are far from the sole birds with significance to Indigenous people of the Southwest (Gershon).

Animals are commonly represented in Pueblo and Southwestern Indigenous pottery, owing to their necessity for sustenance and their spiritual importance. While bears, fish, bats, and composite mythological creatures appear on pottery and other art forms, the Columbia collection in Art Properties has extensive vessels featuring birds. In several creation stories, the birds function as essential allies and confidants of human beings. Birds impact the oral histories of these communities, including the Zuni, Hopi, and Acoma (Forde 370-87). Further, there are explicit connections between birds and rain. Flying birds are allusions to the sky and rain clouds, owing to their role in creation myths and rain dances. The association between birds and rain ties their representation of ceramics back to the spirituality of the earth. The earth, combined with the rain, creates the conditions to dig for clay, and the process allows for vessels that carry water and food to nourish the community. Further, birds are symbols seen in weaving, baskets, and ceremonial items such as crooks and masks (Cole 300-03).

Fig. 3. Unidentified Mimbres artist, Bird vessel with geometric wing design on back, ca. 1100, New Mexico, clay with pigment, H. 3 1/2 x W. 3 1/8 x D. 3 1/2 in. (9 x 8 x 9 cm), Art Properties, Avery Library, Columbia University, Gift of Stanley B. and Caroline Stein (1997.08.017.01).

Fig. 3. Unidentified Mimbres artist, Bird vessel with geometric wing design on back, ca. 1100, New Mexico, clay with pigment, H. 3 1/2 x W. 3 1/8 x D. 3 1/2 in. (9 x 8 x 9 cm), Art Properties, Avery Library, Columbia University, Gift of Stanley B. and Caroline Stein (1997.08.017.01).

Bird imagery on pottery has been passed down as cultural and material knowledge in the Southwest for over 1500 years. Many early examples of Indigenous pottery come from the Mimbres culture, which thrived from 1100-1250 CE. The Mimbres were a community living along the Mimbres mountain range in Southwestern New Mexico and have genetic links with the Hopi and a few other Pueblo tribal nations (Berlo & Phillips 55). While primarily living in cliff dwellings, the Mimbres eventually moved to mud and clay-constructed buildings in the shade of the cliffs. Clay was crucial to their lives for building and creating ceramics that could carry water from the river to their community. The river and the life it spawned were central to Mimbres's daily life and their culture (Brody & Swentzell 14-16). Animals, like in more modern Indigenous Southwest pottery, were a vital iconography represented across Mimbres ceramics. Birds have cultural and symbolic importance, and the black-on-white style of Mimbres pottery inspired generations of artists long into the future (Berlo & Phillips 55-57). Many of the origins of abstract and geometric representations on ceramics began in this period. The above ceramic effigy vessel meshes its natural form with geometric designs. Made with white clay, it sports a painted black zig-zag and line design on its stomach, similar to the design on the turkey in the earlier plate. At the same time, the vessel has realistic eyes, and a beak and tail demonstrate an appreciation and skill in capturing the bird’s form. This small vessel was likely used to store water or some liquid and may have been used or kept around the house. The symbolic importance of the bird seems to have been tied to its practical usage as a way to carry water while reminding the user of the stories and associations between birds, the sky, rain, and thunder.

Fig. 4. Unidentified Hopi artist, Bird effigy vessel, ca. 1900, Arizona, clay with pigment, H. 4 7/8 x W. 8 1/4 x D. 10 3/4 in. (12.3 x 21 x 28 cm), Art Properties, Avery Library, Columbia University, Gift of Stanley B. and Caroline Stein (1997.08.041).

Fig. 4. Unidentified Hopi artist, Bird effigy vessel, ca. 1900, Arizona, clay with pigment, H. 4 7/8 x W. 8 1/4 x D. 10 3/4 in. (12.3 x 21 x 28 cm), Art Properties, Avery Library, Columbia University, Gift of Stanley B. and Caroline Stein (1997.08.041).

Although most of the Native American objects in the Art Properties collection were acquired and collected by Prof. Wendell ter Bush in the early decades of the twentieth century, most of the pottery in this collection was a gift to Columbia from Stanley B. and Caroline Stein in 1997 to support the educational mission of the collection. The bird effigy piece seen here, however, was put on display in the President’s House to showcase some cultural heritage objects from Columbia’s collection but was recently returned to reinforce its educational use and to better consider the importance of this work in appreciation of the ongoing consultations associated with NAGPRA. The vessel was likely made to be used, owing to the handles, and its transformation from a practical item with aesthetic and cultural meaning, to one centered on its cultural importance demonstrates the shifts in art in the Native Southwest. Ceramic vessels of birds are produced to this day, while the use has primarily shifted from practical items used in the home to artwork produced for sale in a market economy. The iconography from the Mimbres period continued long after the end of that culture, which went on to influence and trade with their Ancestral Puebloan neighbors who descended into the Hopi, Zuni, San Ildefonso, and other Pueblo communities. Settler colonialism and engagements between the U.S. military and Indigenous groups in the Southwest contributed to land theft and limited opportunities for Indigenous people to survive. While the U.S. government monitored Indigenous land heavily, with the end of treaty making and the beginning of allotment as the official federal policy after the passing of the Dawes Act in 1887, it pushed all Indigenous people towards a capitalistic economic model and understanding of property. With the railroad expansion and other business enterprises into the American Southwest, settler capitalists, Indigenous entrepreneurs, and artists increasingly saw a market for Pueblo art as a commodity to sell to settlers and tourists. The above bird effigy vessel appears to be an eagle, symbolically representing the Hopi people's power and strength. The wings are fashioned as handles, and their paint is artistically rendered to represent the plumage and coloring of the bird. A beak, legs, and tail are painted or sculpted on, demonstrating a preference for accuracy to the bird's form and the use of the 3D space of the vessel to mirror the bird’s form. Although it is tempting to want to believe the vessel as a bird has spiritual significance, this remains unclear and undocumented, and it may just be an artistic rendition of an eagle. The naturalistic and organic design shares similarities to the Hopi bowl but contrasts with the more geometric patterns of other Pueblo ceramics, reinforcing how pottery created by different Pueblo tribes reflect their distinctive iconography and imagery, such as Zia pots depicting parrots.

Fig. 5. Unidentified Zia artist, Polychrome pot with large red bird and flower designs, ca. 1890, New Mexico, clay with pigment, H. 9 x W. 11 x D. 11 in. (23 x 28 x 28 cm), Art Properties, Avery Library, Columbia University, Gift of Stanley B. and Caroline Stein (1997.08.046).

Fig. 5. Unidentified Zia artist, Polychrome pot with large red bird and flower designs, ca. 1890, New Mexico, clay with pigment, H. 9 x W. 11 x D. 11 in. (23 x 28 x 28 cm), Art Properties, Avery Library, Columbia University, Gift of Stanley B. and Caroline Stein (1997.08.046).

This hand-coiled Zia pot is similar to another in the collection and is notable for depicting several birds on different planes of the pot. Floral designs surround large depictions of parrots on the lower to the middle level, with smaller birds on the narrower higher level. This pot was made around 1890 and may have been used, given the wear and quality of the piece. This vessel may have been used by Indigenous individuals for eating, drinking or storing goods, while later pots of this style were designed to be sold to collectors. The wear and subtle design differences suggest this, especially when compared to the more recent Zia pot from 1920, which appears to have been produced specifically for trade and in the context of collection rather than use as a daily object.

A similar pattern and style of arranging the birds is seen on this pot. While the smaller birds are not present, a parrot is visible on the lower level, while what appears to be a roadrunner is seen on the plane above. While flowers still surround the birds, which suggests their natural setting, the botanic designs are more stylized, with some sharp angles and more prevalent use of negative space. Further, two curved bands separate the planes and the birds, contrasting the white background, beige bodies, and red base and designs. The increase in designs may have better fit the expectations of an art market that pursued authenticity from Native artists while rewarding recognizable and distinct styles. The change in use and wear shows how, over three decades, ceramics had gone from primarily being used in daily life to being integrated into the capitalist economy and trading posts in the American Southwest.

Fig. 6. Unidentified Zia artist, Polychrome pot with yellow birds separated by double red lines, ca. 1920, New Mexico, clay with pigment, H. 10 x W. 12 x D. 12 in. (22.5 x 30.5 x 31 cm), Art Properties, Avery Library, Columbia University, Gift of Stanley B. and Caroline Stein (1997.08.049).

Fig. 6. Unidentified Zia artist, Polychrome pot with yellow birds separated by double red lines, ca. 1920, New Mexico, clay with pigment, H. 10 x W. 12 x D. 12 in. (22.5 x 30.5 x 31 cm), Art Properties, Avery Library, Columbia University, Gift of Stanley B. and Caroline Stein (1997.08.049).

The shift over time from Pueblo ceramics' origins as a utilitarian item to being a collected and decorative item, to again being seen as an instructional item demonstrates how the design of the bird has held and continues to hold practical and interpretive power and how it changes, over its lifetime. Birds hold symbolic and practical meaning to Indigenous people. They are represented on pottery and through effigy vessels that hold water and demonstrate the centrality of birds to the environment and Pueblo belief systems. Using these objects for study in Art Properties reveals the artistic traditions of creating and decorating Pueblo ceramics and the cultural importance of portraying birds and animals as signifiers of belief and the relationship between humans and the environment. Many of those traditions carry on into commercially produced ceramics, which were sold and traded for profit and survival to take care of an artists’ family during the early 20th century. These practices continue today, as Indigenous artists create ceramics that reflect their culture and express their commitments to their families and surroundings. While NAGPRA requires the return of Indigenous art with ceremonial or religious significance, the symbolic associations with birds and the pots may not have risen to the level of cultural significance. Their use as items in daily life and century-long production for settlers positions them as a source of knowledge and learning in the collection.

WORKS CITED

American Museum of Natural History, "The Spider Woman," Totems to Turquoise (2004–2005), exhibition website, https://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/totems-to-turquoise/native-american-cosmology/the-spider-woman (viewed April 7, 2023).

Berlo, Janet Catherine, and Ruth B. Phillips. Native North American Art. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford Univ. Press, [2015]. E98.A7 B47 2015

Brody, J. J., and Rita Swentzell (Kah'p'oo Owinge). To Touch the Past: The Painted Pottery of the Mimbres People. New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1996. N6502 So87 B783

Cole, Sally J. "Roots of Anasazi and Pueblo Imagery in Basketmaker II Rock Art and Material Culture." Kiva 60, no. 2 (Winter 1994): 289–311. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30246661.

Espinosa, Aurelio M. "Pueblo Indian Folk Tales." The Journal of American Folklore 49, no. 191/192 (Jan.-Jun. 1936): 69–133. https://doi.org/10.2307/535486.

Forde, C. Daryll. "A Creation Myth from Acoma." Folklore 41, no. 4 (December 1930): 370–87. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1255991.

Gershon, Livia. "In the Ancient American Southwest, Turkeys Were Friends, Not Food." Smithsonian Magazine, December 2, 2020, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/800-year-old-blanket-holds-clues-turkey-farming-american-southwest-180976438 (viewed April 7, 2023).

Hutchinson, Elizabeth. Lecture. "The Arts of Native America," Department of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia University, January 25, 2023.

Parkman, E. Breck. "Creating Thunder: The Western Rain-Making Process." Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology 15, no. 1 (1993): 90–110. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27825509.

Swan, Edith. "Laguna Symbolic Geography and Silko’s 'Ceremony.'" American Indian Quarterly 12, no. 3 (Summer 1988): 229–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/1184497.

Vecsey, Christopher. "The Emergence of the Hopi People." American Indian Quarterly 7, no. 3 (Summer 1983): 69–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/1184257.