Mussolin Essay

MAURO MUSSOLIN, New York University, Florence & LEONARDO PILI, Analysis of the Manuscript’s Paper Essay Appendix 1 Appendix 2 Appendix 3

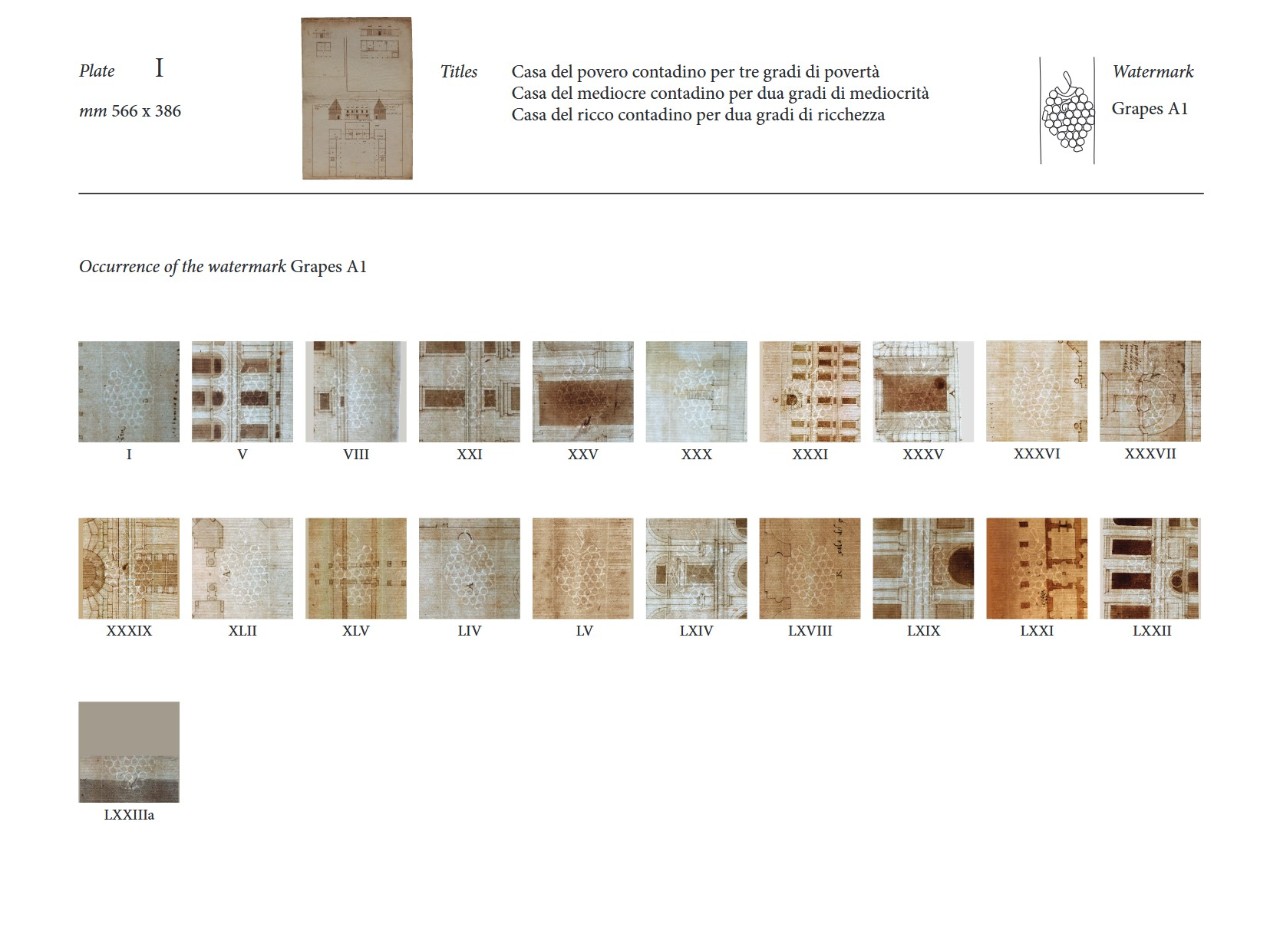

Fig. 1. Detail of Appendix 3 showing instances of watermarks.

Fig. 1. Detail of Appendix 3 showing instances of watermarks.

In 1942, the Avery Librarian at Columbia University, William Bell Dinsmoor, published a long essay on an Avery manuscript, proving that the volume contained the first autograph version of the unpublished Book VI On domestic architecture by Sebastiano Serlio.1 In the wider perspective of Serlio's grand editorial enterprise, Dinsmoor offered the first, most persuasive, and best sustained genesis of Book VI, dating its execution between 1541 and 1546. His analysis was supported by a very rigorous, yet strongly positivistic, belief in the possibility of dating paper through watermarks, which was at that time a ground-breaking method narrowly based on the titanic work by Charles-Moïse Briquet, Le filigranes. Dictionnaire historique des marques du papier (1907).2 Since then, scholars have agreed with Dinsmoor's conclusions, fully validating his methodology on paper analysis.3

Today, in a period of increased attention toward material studies, it seems noteworthy to challenge Dinsmoor's interpretations. The occasion is provided by new, high-resolution photography of the manuscript. Furthermore, this analysis will provide an updated set of considerations to contextualize paper and papermaking in sixteenth-century France. Although provisional, our additional thoughts will try to broaden the view of the field, hoping to rejuvenate the methodology and stimulate fresh interest in the material. A series of appendices detail the location and type of the watermarks within the manuscript.

To explain the current structure of the manuscript and its material characteristics it is convenient to start with a brief account of the genesis of the work. As previously mentioned, Dinsmoor fixed the beginning of Book VI shortly after Serlio's 1541 arrival in Fontainebleau to act as the architect of King Francis I. At that time, the manuscript was nothing other than a gathering of loose sheets displayed in-plano, intermixed with smaller sheets bearing the text, also in-plano. The first version of Book VI was almost completed when Serlio moved to Lyon in May 1546. The death of the King, in March 1547, might explain the execution of a revised version of Book VI, now preserved at the Bayerische Staatbibliothek in Munich.4 This copy was lavishly executed on vellum for presentation to King Henry II, an event which possibly occurred in 1549-50. The existence of a third version, dated around 1553, which is now lost, is only assumed on the basis of a complete series of printer's proofs of the illustrations, made on seventeenth-century paper, now held at the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek in Vienna. Since those illustrations show an evolution of designs contained in the second Munich version, the late proofs might have been printed from wooden boards specifically carved to imprint the third and final version of Book VI.5

It is unclear if the Avery manuscript remained in the hands of Serlio, as Dinsmoor firstly suggested, or if it was sold to Jacopo Strada in 1553 together with the Munich version, as proposed by Dirk Jacob Jansen.6 Unquestionably, the original sequence of plates was soon changed, as shown by the sixteenth-century multiple numbering with letters and cyphers which are not in Serlio's handwriting.7

There are hints of the presence of the manuscript in late sixteenth- or early seventeenth-century France, as it was in the atelier of Jacques Androuet du Cerceau and his grandson Salomon de Brosse, where it was consulted by Pierre Le Muet.8 Almost a full century later, the manuscript was still in France where it was consistently altered. The drawings were seemingly trimmed to eliminate frayed edges and pasted on heavy French paper.9 These mountings were then folded in half together with drawings, acquiring the look of a pile of in-folio. The same paper was used to add a new title page, that bears that misleading inscription which Dinsmoor has discussed at length: “viii livre d / viii libro di serlio / m:s: / Architectura.”10

Around the first quarter of the eighteenth century the book arrived in Britain. This is proved by a bookplate from the Bird family of Cheshire, displayed on the verso of the title page. On that occasion, for the first time, the manuscript was bound as a book with leather covers. In the nineteenth century, the manuscript passed through several Scottish collections, and finally entered the library of Dr. David Laing of Edinburgh, where it remained with no apparent transformations. After the auction of Laing's house on December 23, 1880, Serlio's manuscript landed in London, around 1919, where it was purchased by the rare book dealer Bernard Quaritch. To better present the manuscript for the upcoming sale, Quaritch ordered a few disconcerting transformations that massively impacted the original structure of the manuscript. The old and damaged binding was replaced with a new leather cover and another title page was added.11 Mountings were cut out on the back to show the verso of the drawings, transforming them into frames and displayed again in-plano.12 Finally, text sheets were pasted on the lower edge of the corresponding drawings, often incorrectly, and flapped on top of them. This was the puzzling look of the volume in 1920, when Dinsmoor saw it for the first time in London. The formal acquisition by Columbia University happened in 1924, when the manuscript finally entered the catalogue of the Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library.

Two decades later, in 1942, Dinsmoor wrote the first part of his essay, “On the literary remains of Sebastiano Serlio” for The Art Bulletin, announcing the discovery of the Avery manuscript. The second part, cited thus far, appeared in the following issue. The opportunity to publish a facsimile edition of the Avery manuscript, optimistically announced by Dinsmoor, was only taken up after his death in 1973 by Myra Nan Rosenfeld, who published it in 1978, with a foreword by Adolf K. Placzek and an introduction by James S. Ackerman.13 Rosenfeld's essay in the volume put forward new insights on the genesis of the manuscript, proposing a few corrections to the internal sequence of the drawings.14 Over the years, Rosenfeld returned to Book VI, providing further interpretation and new insight to the material aspect.15 Later scholars were uninterested in the material structure of the Avery manuscript, and haven't put forward any additional paper analysis.

At the present day, the Avery manuscript appears again as a gathering of loose sheets. A few decades ago the book was unbound and a systematic campaign of removal of the framings followed. However, this operation was cautiously stopped midway, with the present result that the assorted loose sheets of Book VI exist in multiple displays: on one hand, there are fifteen unframed drawing folios (plates I-XI, XLVI, XLVII, LIV, LXXIII separated in three pieces), to which are related fourteen loose texts (one text is missing), once pasted to their corresponding frames; on the other hand, there are fifty-nine remaining drawings mounted in their frames, forty-nine of which have the text sheets still glued and folded as a flap at the corresponding lower edge. The average measurement of the plates with drawings varies between 385 and 835 mm in height and 365 and 667 mm in width, those of text sheets varies between 140 and 835 in height and 194 and 470 mm in width.

Dinsmoor and Rosenfeld analyzed the sheets of the Avery manuscript with exceptional attention, relying faithfully on Briquet's Dictionnaire. Dinsmoor separated the sheets with drawings from the sheets with text. Then he noticed that twelve sheets of drawings were composed as a collage of paper fragments, counting a total number of ninety-six pieces of paper, with a corresponding growth in the occurrence of watermarks. Then, he grouped the watermarked paper into five distinct “varieties” (I, Grapes; II, Grapes «BM»; III, Grapes «DR»; IV, Shield «PS»; V, Pitcher fragmented). Analogously, he grouped the sixty-three sheets with text into five other “varieties” of paper (IV, Shield «PS», same as before; VI, Pitcher «AE»; VII, Shield fleur-de-lys; VIII-IX, Serpent; IX, Serpent). Moreover, he detected twenty-three text sheets (many of them in their original size), plus another five fragments inserted in the drawings, as a variety of paper characterized by a complete absence of watermarks. Based again on Briquet, he also tried to define the original size of these sheets regarding their final functions, another fundamental contribution to the understanding of Serlio's design process.16

Dinsmoor's multilayered reconstruction of the chronology of Book VI may be better summarized in his own words: “By this method of classification [of paper though their watermarks] we obtain seven distinct strata (a-g) in the manuscript, six of them covering the six years from 1541 to 1547, so that with a slight risk of error they may be dated tentatively in the somewhat schematic form presented on page 139”,17 the “Table of Drawings as Dated by Watermarks”.18 In her later account, Rosenfeld steps away from the previous reconstruction: “In contrast to Dinsmoor, only four general phases seem evident to me: three for the execution of the drawings and one for the writing of the text, with the text being written only after all the illustrations had been completed.”19 Nevertheless, she accepted Dinsmoor's detailed paper analysis with minimal changes and presented it in a synoptic table that makes an explicit reference to their common source, “Paper Types Used in the Avery Manuscript with Watermarks According to C. M. Briquet, Les Filigranes, Amsterdam, 2nd edition, 1968.”20

In conclusion, in Briquet's Dictionnaire both Dinsmoor and Rosenfeld found what they wanted to find. Regarding their reconstructions, Briquet was fundamental to the analysis of size and function of the sheets, but unsuitable for the chronological reconstruction of drawings and text.

All considered, is the method of dating paper with watermarks still authoritative today? If so, how much can we rely on catalogs of watermarks such as Briquet?

Such an answer should be resolutely affirmative, and watermark dictionaries today have a critical importance, even more so than a century ago. As Briquet clearly explained in the Avant-propos to Les filigranes, the method to date the paper with watermarks is quintessentially empirical. Amendments and tweaks are necessary to overcome missing information:

Avant tout, affirmons bien haut que, théoriquement, toute feuille de papier filigrané porte en elle-même son acte de naissance, la marque dont elle est munie devant faire connaître la date et le lieu de sa fabrication. Mais, en pratique, nous ne parvenons à déchiffrer cet acte de naissance que d'une manière imparfaite et approximative, parce que nous manquons des données indispensables pour le lire.21

While dating watermarks remains a rough method, the information included in Briquet is still a crucial instrument in tracing the network of paper as a remunerative product in commerce and a good used daily and recycled in time.

To avoid a naïve use of watermarks in paper analysis, a basic overview of papermaking is required. Since the thirteenth century, the production of quality paper followed standardized procedures based on the achievements reached in the Italian city of Fabriano. Paper “ad usum fabrianensis,” or made according to the rules established by the Guild of the papermakers in Fabriano, soon became synonymous with exemplary manufacture and universal excellence.

The success of that product was based on a few essential factors and a very accomplished economy of means. First, Fabriano's papermakers developed a method to size the paper with animal gelatin that gave greater consistency to the support, waterproofing the surface for better use of pen and ink, and preserving the sheets from aging quickly. Second, they started to identify the different qualities and sizes of sheets with a distinctive symbol that characterized each variety produced during a specific period of time. For these reasons the watermarks, not so different from a modern barcode, were able to set up new criteria for the traceability of each single sheet, with fundamental outcomes for the control of the quality of the product and its corresponding prices. Third, the rational proportions of the sheets and the arrays of thickness of the reams regularly sold contributed significantly to the standardization of paper varieties over time.

City governors and principality lords were always interested in the economic effects derived from papermaking, and they often invited papermakers from Fabriano to establish new paper mills in their regions. During the fourteenth century, Fabriano constantly exported papermakers throughout the Italian peninsula and the rest of Europe, wherever the waters ran clean and abundant and proximity to cities easily provided the second-hand rags needed as a raw material. The impact of this product on the market was substantial, and it provoked a general increase in quality standards and technological skill. In a century, a new constellation of paper mills was founded. As early as the middle of the fifteenth century, France gradually became less dependent upon Italian imported paper. A century later, France was one of the most important producers, exporting its worthy paper to Spain, England, the Netherlands, and the whole Rhine basin.

If Fabriano's paper set the general standards of papermaking, sizes and qualities were adapted to specific regional tradition, creating local variants. Watermarks were also based on native shapes and traditional patterns. Until the mid-seventeenth century the most important steps of papermaking remained the same. Second-hand rags were carefully selected and put into pools with fresh water to ferment. Then, they were crushed to become a fine pulp by a hydro-powered trip hammer. Quality and color of the fibers determined the quality of the paper: the whiter and finer the rags, the better and finer the paper. The pulp was then placed in a vat, attended by a postman and a couple of vatmen. The vatmen alternated dipping their molds into a vat of pulp to take on a sufficient quantity to form similar sheets of the desired substance. Then, the mold was passed to the postman who pressed the wet sheet onto a larger piece of felt, returning the mold to the corresponding vatman, who started the process again.22

It appears evident that the molds used to make the same variety of paper were identical, and for this reason they are called twin molds. The intention of this duplication was to avoid deadtime and to better coordinate the work among vatmen and postman.23 The only distinction between the twin molds was the different position of the watermarks – in one case it was displayed in the center of the left half, in the other the center of the right half. Consequently, twin watermarks not only often have a mismatched shape, but they also aged differently. In this case, watermarked sheets from the same ream might show significant dissimilarities.

Observing the Avery manuscript closely we can see all the various characteristics of the paper produced in France in the middle of the sixteenth century, a supply very well-suited to their final use in quality, formats, and consequently costs. Bigger sheets destined for drawings are of a better quality, smaller sheets reserved for text are of a medium or lower quality. The symbols of the watermarks are likewise typical of the geographical area: grapes, pitcher, fleur-de-lys, a salamander. Other regional characteristics are also evident. Unwatermarked paper destined for writing was common in France at the time, but was extremely rare in Italy. The same is true regarding the sizes of the sheets. There are traditional formats derived from Italy, such as “Royal” (415 x 600 mm) for drawings (Grapes A1-2; Grapes B1-2; Grapes C), and “Commune” (310 x 440 mm) for writing (Vase A1-2; Serpent A1-2; Serpent B), but also a diminished format typical of the French, such as “Petit Royal” (415 x 540 mm) for drawings (Shield «PS» A1-2; Shield «PS» B1-2; Shield «PS» C), and “Petit Papier” (280 x 390 mm) (for text (Shield «Lily» A1-2). Unwatermarked paper was used for writing and those sheets are all “Medium” (350 x 500 mm). Also typical of French manufacture was the very narrow interval between the chain lines present in the “Petit Royal” (Shield «PS») and two of the “Commune” (Vase A1-2; Vase B).24 It is not surprising to find a more regular production for those formats directly derived from the Italian tradition used for drawing (Grapes A1-2; Grapes B1-2; Grapes C), while the other paper used for writing is less regular and more roughly executed.

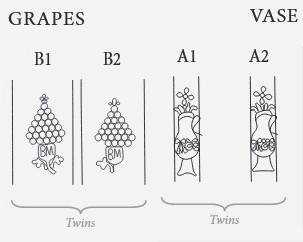

Fig. 2. Tracings of watermarks for some twin molds.

Fig. 2. Tracings of watermarks for some twin molds.

Our final remarks are focused on twin molds, a peculiarity completely overlooked by Dinsmoor and Rosenfeld. As mentioned, all the sheets have been photographed in raking light, and it is finally possible to provide a complete map of all the watermarks. We have tried to match the twin couples among all the sheets of the manuscript, and our preliminary outcomes are encouraging. The couple of watermarks Grapes B1-2 are regular and perfectly specular (B1 right handed, B2 left handed), while the other three couples Grapes A1-2, Shield «Lily» A1-2, and Vase A1-2, show irregularities. In those cases, we haven't yet distinguished left-hand from right–hand examples yet, and only theoretically we might suggest for each couple a specular disposition of their corresponding watermarks. A very challenging case is offered by the French format “Petit Royal” (never used as a full sheet, but always in halves for text and fragments for drawings), whose watermarks are present twelve times in seven variants (Shield «PS» A1-2; Shield «PS» B1-2, with B1 in three sub-variants; Shield «PS» C). The single case of variant Shield «PS» C was sewn along the chain line, has no match and is right handed. The remaining eleven watermarks Shield «PS» A and B, oddly enough, are all left handed. Because of the presence of the letters «PS», that excludes the possibility of a specular disposition, we may tentatively suggest two different scenarios: the more complicated one, derived from two couples of twin molds (A1-2; B1-2), both left handed, where the variant B2 is differently oriented, while the variant B1 might have drifted over time to a different position (sub-variants 1-3), due to a faint seam in the laid lines; the simpler one, derived from one single couple of twin molds (A and B), all left handed, where the same watermark always drifted in a different way for the same reason. An evident example of aged molds, incorrectly kept, or badly matched: a significant departure from tradition, as a result of a different organization of the productive system.25

The following pages contain the results of our analysis on the paper of the Avery manuscript, and they are organized in three separate appendices.

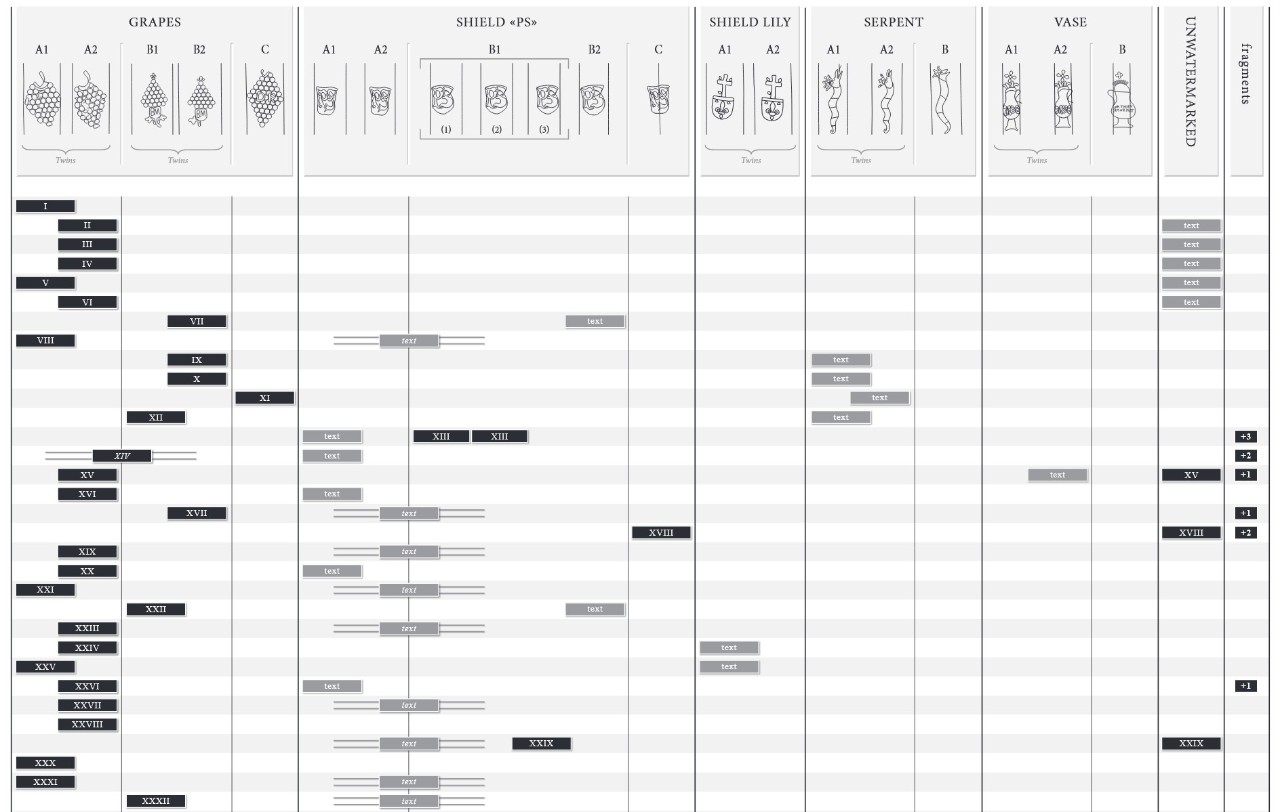

Appendix 1 represents a development of the synoptic table published by Rosenfeld, and presents all the variants of the watermarks according to their potential matches to form twin molds. Plates with drawings are indicated in black, sheets with text in grey. A line containing multiple elements indicates that the sheet is composed by a corresponding number of pieces. At glance, each column of the table shows the corresponding consistency of twin sheets of that variety. The last two columns contain on the left the occurrences of laid paper originally unwatermarked, and on the right the additional number of fragments cut out from undetectable sheets. Elements displayed across two columns are unwatermaked, but they were certainly cut out from those sheets whose watermarks are included in the corresponding columns. This is the case of the half sheets (text VII, XVII, XVIII, XIX, XXI, XXII, XXIII, XXVII, XXXI, XXXII, XLIV) without watermark but evidently cut out from those “Petit Royal” sheets used for writing, and it is also the case for the two big fragments used for drawing (plates XIV, XXXIV), evidently cut out from one of those “Royal” sheets with Grapes.

To summarize, here there are a few examples: the first column, that corresponds to Grapes B1-2, indicates eleven sheets made with mold B1, and ten with mold B2; across the columns Grapes A1-2 and Grapes B1-2,

Fig. 5. Detail of Appendix 3.

Fig. 5. Detail of Appendix 3.

are the drawings XIV and XXXIV, indicating fragments of paper both compatible with Grapes A1-2 and Grapes B1-2, for this reason shown in italics; line XXIX indicates instead that the plate with the drawing is composed of two pieces (Shield «PS» B1 in the sub-variant 3, and a fragment cut out from a sheet originally unwatermaked), while the corresponding sheet with the text is a fragment of paper with no watermark, in this case perfectly compatible with Shield «PS», in one of its variants A and B.

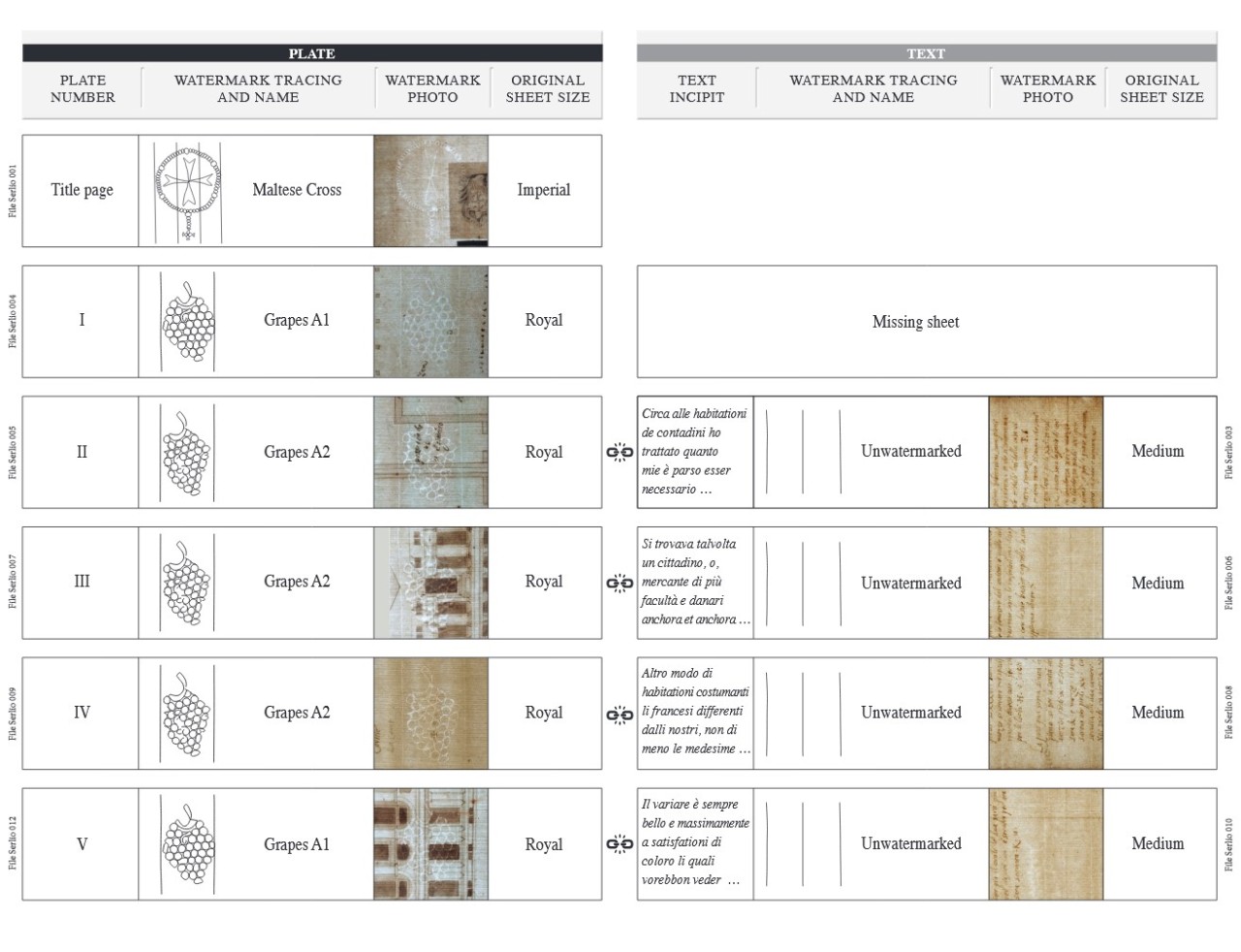

Appendix 2 maps the occurrence of tracing and photography of the watermarks, both in plates with drawings (at left) and sheets with text (at right), following the sequence of the sheets in the manuscript provided by Rosenfeld. Additional information, such as the original format of each sheet and incipit of the corresponding text, are provided. A symbol at the center of the line indicates if plate and text are separated or still pasted together.

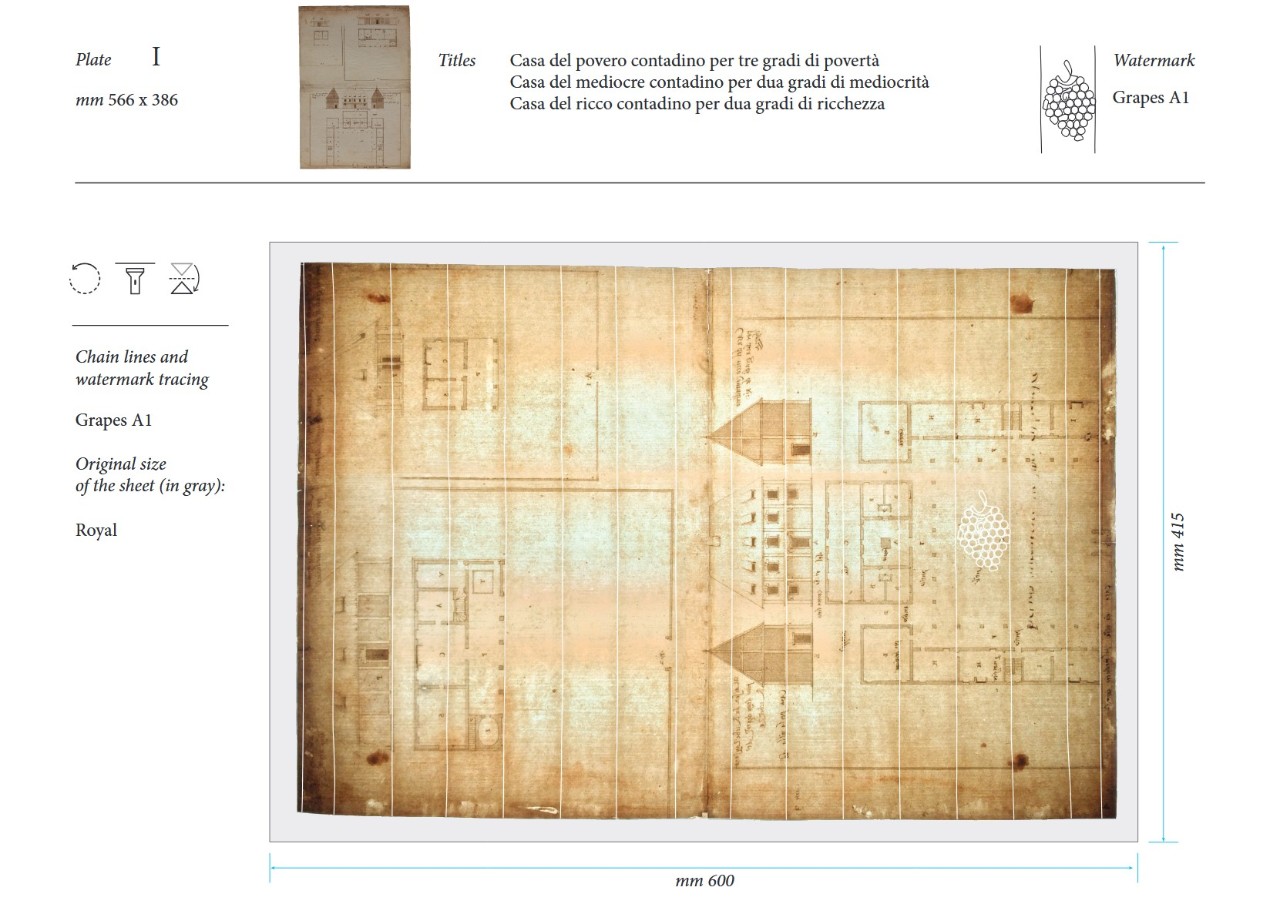

Appendix 3 is dedicated to a detailed analysis of the nineteen watermarks in the context of their corresponding typology of sheets (as presented in the first appendix). All pages show a recurring heading and a column on the left. The heading includes the general information about the plate (number, dimensions, icon of the sheet oriented in its canonical position – rectos oriented in respect of the sense of reading and with drawings facing up – title of the drawing or incipit of the text, tracing of the corresponding watermark and name of the type with its variants). The column on the left contains the symbols to describe the operations applied to the main image with respect to the icon of the heading (in the sense of rotation; exposure to transmitted light; horizontal or vertical reflection). Additional considerations will appear in the box below.

Each typology of watermark is described in the sequence of three (or in some cases more) plates. The first page shows the sheet with visible light, the second with transmitted light, the third offers a tracing of the chain lines and the watermark, the fourth page lists all the images of the same watermark in the manuscript, mapping its occurrence. Those supplementary pages are dedicated to sheets with multiple fragments of paper, where the hypothetical format and typology of the sheet is also provided.

1 William Bell Dinsmoor, “The Literary Remains of Sebastiano Serlio. I-II,” The Art Bulletin, nn. 1-2, (24, 1942), 55-91, 115-154.

2 Charles-Moïse Briquet. Le filigranes. Dictionnaire historique des marques du papier dès leur apparition vers 1282 jusqu’en 1600, 4 voll., Geneve 1907.

3 Dinsmoor, “The Literary Remains of Sebastiano Serlio. I-II,” 131-135.

4 Marco Rosci, Il Trattato di architettura di Sebastiano Serlio. Sesto libro delle habitationi di tutti le gradi degli huomini (I.T.E.C. Editrice: Milano 1966), 2 voll.; Francesco Paolo Fiore, Premessa. Sesto Libro, in Sebastiano Serlio, Architettura civile. Libri Sesto Settimo e Ottavo nei manoscritti di Monaco e Vienna, ed. Francesco Paolo Fiore (Edizioni Il Polifilo: Milano 1994), 1-26; Sabine Frommel, Sebastiano Serlio architetto (Electa: Milano 1998), 355-359.

5 Konrad Oberhuber, “Sebastiano Serlio,” Albertina Informationen (5, 1968), 2-3; Myra Nan Rosenfeld, “Sebastiano Serlio's Drawings at the Nationalbibliothek in Vienna for his Seventh Book on Architecture,” in The Art Bulletin (LVI, 1974), 401-409; Fiore, Premessa. Sesto Libro, in Sebastiano Serlio, Architettura civile. Libri Sesto Settimo e Ottavo nei manoscritti di Monaco e Vienna, 1-26; Based on architectural analysis, Sabine Frommel argued that the copy at Vienna might better be the second version of Book VI, as anticipation of the more mature version of Munich, Frommel, Sebastiano Serlio architetto, 356-357. See also Fiore, “Le mauscript du Sesto Libro conservé à Munich”, in Sebastiano Serlio à Lyon. Architecture et imprimerie. Volume 1: Le Traité d'architecture de Sebastiano Serlio: une grande entreprise éditoriale au XVIe siécle (Mémoire active: Roanne 2004), 169, and Fiore, “Les épreuves d'imprimerie da Sesto Libro conservées à Vienne”, in Sebastiano Serlio à Lyon. Architecture et imprimerie. Volume 1: Le Traité d'architecture de Sebastiano Serlio: une grande entreprise éditoriale au XVIe siécle (Mémoire active: Roanne 2004) 173.

6 Dinsmoor, “The Literary Remains of Sebastiano Serlio. I-II,” 140; Dirk Jacob Jansen, Jacopo Strada editore del Settimo Libro, in Sebastiano Serlio, Sesto Seminario Internazionale di Storia dell'Architettura, Centro Internazionale di Studi di Architettura “Andrea Palladio”, Vicenza 31 agosto-4 settembre 1987, ed. Christof Thoenes (Electa: Milano 1989), 207, in particular note 6.

7 Dinsmoor, “The Literary Remains of Sebastiano Serlio. I-II,” 124; Myra Nan Rosenfeld, Sebastiano Serlio, On Domestic Architecture. Different Dwellings From the Meanest Hovel to the Most Ornate Palace. The Sixteenth-Century Manuscript of Book VI in the Avery Library of Columbia University, foreword by Adolf K. Placzek; Introduction by James S. Ackerman; Text by Myra Nan Rosenfeld (New York-Cambridge MA-London: The Architectural History Foundation and The MIT Press, 1978), 29.

8 David Thompson, Renaissance Paris. Architecture and Growth 1475-1600 (Zwemmer: London 1984), 18;. Myra Nan Rosenfeld, Recent Discoveries about Sebastiano Serlio's Life and His Publications, introduction to Serlio on Domestic Architecture, Dover Paperback Publications (paperback edition of Rosenberg 1978) (Mineola: Dover, 1996), 1-8.

9 The analysis of the paper of the mountings falls outside the goal of the present study.

10 Dinsmoor, “The Literary Remains of Sebastiano Serlio. I-II,” 117-118.

11 This leather cover and the related title page are now eliminated.

12 Rosenfeld, Sebastiano Serlio, On Domestic Architecture. Different Dwellings From the Meanest Hovel to the Most Ornate Palace. The Sixteenth-Century Manuscript of Book VI in the Avery Library of Columbia University, 27.

13 See also Myra Nan Rosenfeld, “Sebastiano Serlio's Late Style in the Avery Library Version of the Sixth Book on Domestic Architecture,” Journal of the Architectural Historians, vo. XXVIII, (3, 1969), 155-172 and Rosenfeld, “Sebastiano Serlio's Drawings at the Nationalbibliothek in Vienna for his Seventh Book on Architecture”, The Art Bulletin, n. 3 (56, 1974) 401-409.

14 Dinsmoor, “The Literary Remains of Sebastiano Serlio. I-II,” 115-154. Rosenfeld, Sebastiano Serlio, On Domestic Architecture. Different Dwellings From the Meanest Hovel to the Most Ornate Palace. The Sixteenth-Century Manuscript of Book VI in the Avery Library of Columbia University, 27-28.

15 Myra Nan Rosenfeld, Sebastiano Serlio's Contributions to the Creation of the Modern Illustrated Architectural Manual, in «Sebastiano Serlio», Sesto Seminario Internazionale di Storia dell'Architettura, Centro Internazionale di Studi di Architettura “Andrea Palladio”, Vicenza 31 agosto-4 settembre 1987, ed. Christof Thoenes (Electa: Milano 1989), 102-110. Rosenfeld, Recent Discoveries about Sebastiano Serlio's Life and His Publications, 1-8. Myra Nan Rosenfeld, Le dialogue de Serlio avec ses lecteurs et mécènes en France dans le Sesto Libro, in Sebastiano Serlio à Lyon. Architecture et imprimerie. Volume 1: Le Traité d'architecture de Sebastiano Serlio: une grande entreprise éditoriale au XVIe siècle (Mémoire active: Roanne 2004), 153-166.

16 Dinsmoor, “The Literary Remains of Sebastiano Serlio. I-II,” 131-135.

17 Dinsmoor, “The Literary Remains of Sebastiano Serlio. I-II,” 140. According to Dinsmoor, the seventh strata (g) is represented by plate XI (defined as watermark III, Grapes «DR», from ca. 1551). Scholars agree that these drawings might be a later addition to the original sequence, a hypothesis further supported by the content, the well-known project known as the «Grand Ferrare» in Fontainebleau, the suburban residence for the Cardinal Ippolito d'Este. See Frommel, Sebastiano Serlio Architetto, 225-227.

18 Dinsmoor, “The Literary Remains of Sebastiano Serlio. I-II,” 139.

19 Rosenfeld, Sebastiano Serlio, On Domestic Architecture. Different Dwellings From the Meanest Hovel to the Most Ornate Palace. The Sixteenth-Century Manuscript of Book VI in the Avery Library of Columbia University, 32.

20 Rosenfeld, Sebastiano Serlio, On Domestic Architecture. Different Dwellings From the Meanest Hovel to the Most Ornate Palace. The Sixteenth-Century Manuscript of Book VI in the Avery Library of Columbia University, 84. The watermark in the text corresponding to plate XV should be placed on the column on its right, corresponding to the watermark Pitcher «AE».

21 Briquet, Le filigranes. Dictionnaire historique des marques du papier dès leur apparition vers 1282 jusqu’en 1600, vol. 1, c. xviii.

22 The post with the sheets of wet paper and felts were then placed under a press to drain out the water. After that, the sheets were laid apart from the felts and hung on drying lines, sized with animal gelatin once dry, and then dried again.

23 Each mold consisted of a rectangular wooden frame over which brass wires were stretched to act as a sieve to permit the water to drain away from the pulp fibers. These sieves were provided with a wooden removable frame, the deckle, fitting exactly the edges, and keeping the required thickness of fiber pulp on the wire. The depth of the deckle varied according to the substance of the sheet being made.

24 Briquet, Le filigranes. Dictionnaire historique des marques du papier dès leur apparition vers 1282 jusqu’en 1600, vol. 1, p. 4.

25 For further consideration on paper and papermaking see: Mauro Mussolin, In controluce: alcune osservazioni sull'uso della carta nei disegni architettonici di Michelangelo in Casa Buonarroti, in Michelangelo e il linguaggio dei disegni di architettura, atti del convegno (Firenze, 29-31 gen. 2009), ed. Golo Maurer, Alessandro Nova (Marsilio: Venezia 2012), 287-311. Mauro Mussolin, Michelangelo e i disegni di figura: alcune considerazioni sulla carta e sull’uso dei fogli di Casa Buonarroti e del Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe degli Uffizi, in Michelangelo als Zeichner, akten des Internationalen Kolloquiums (Wien, Albertina-Museum, 19-20 Nov. 2010), eds. Claudia Echinger-Maurach, Achim Gnann, Joachim Poeschke (Rhema-Verlag: Münster 2013), 145-165.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Le filigranes. Dictionnaire historique des marques du papier dès leur apparition vers 1282 jusqu’en 1600, 4 voll., Geneve 1907.

William Bell Dinsmoor, The Literary Remains of Sebastiano Serlio. I-II, in «The Art Bulletin», nn. 1-2, vol. 24, 1942, pp. 55-91, 115-154.

Johannes Erichsen, L'Extraordinario Libro di Architettura. Note su un manoscritto inedito, in «Sebastiano Serlio», Sesto Seminario Internazionale di Storia dell'Architettura, Centro Internazionale di Studi di Architettura “Andrea Palladio”, Vicenza 31 agosto-4 settembre 1987, a cura di Christof Thoenes, Electa, Milano 1989, pp. 190-195.

Francesco Paolo Fiore, Premessa. Sesto Libro, in Sebastiano Serlio, Architettura civile. Libri Sesto Settimo e Ottavo nei manoscritti di Monaco e Vienna, a cura di Francesco Paolo Fiore, Edizioni Il Polifilo, Milano 1994, pp. 1-26.

------, Le mauscript du Sesto Libro conservé à Munich, in «Sebastiano Serlio à Lyon. Architecture et imprimerie. Volume 1: Le Traité d'architecture de Sebastiano Serlio: une grande entreprise éditoriale au XVIe siécle», Mémoire active, Roanne 2004, pp. 167-170.

------, Les épreuves d'imprimerie da Sesto Libro conservées à Vienne, in «Sebastiano Serlio à Lyon. Architecture et imprimerie. Volume 1: Le Traité d'architecture de Sebastiano Serlio: une grande entreprise éditoriale au XVIe siécle», Mémoire active, Roanne 2004, pp. 171-173.

Sabine Frommel, Sebastiano Serlio architetto, Electa, Milano 1998.

Dirk Jacob Jansen, Jacopo Strada editore del Settimo Libro, in «Sebastiano Serlio», Sesto Seminario Internazionale di Storia dell'Architettura, Centro Internazionale di Studi di Architettura “Andrea Palladio”, Vicenza 31 agosto-4 settembre 1987, a cura di Christof Thoenes, Electa, Milano 1989, pp. 207-215.

Mauro Mussolin, In controluce: alcune osservazioni sull'uso della carta nei disegni architettonici di Michelangelo in Casa Buonarroti, in Michelangelo e il linguaggio dei disegni di architettura, atti del convegno (Firenze, 29-31 gen. 2009), a cura di Golo Maurer, Alessandro Nova, Marsilio, Venezia 2012, pp. 287-311.

-----, Michelangelo e i disegni di figura: alcune considerazioni sulla carta e sull’uso dei fogli di Casa Buonarroti e del Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe degli Uffizi, in Michelangelo als Zeichner, akten des Internationalen Kolloquiums (Wien, Albertina-Museum, 19-20 Nov. 2010), Claudia Echinger-Maurach, Achim Gnann, Joachim Poeschke (Hgg.), Rhema-Verlag, Münster 2013, pp. 145-165.

Konrad Oberhuber, Sebastiano Serlio, «Albertina Informationen», 1968, n. 5, pp. 2-3.

Marco Rosci, Il Trattato di architettura di Sebastiano Serlio. Sesto libro delle habitationi di tutti le gradi degli huomini, 2 voll., I.T.E.C. Editrice, Milano 1966.

Myra Nan Rosenfeld, Sebastiano Serlio, On Domestic Architecture. Different Dwellings From the Meanest Hovel to the Most Ornate Palace. The Sixteenth-Century Manuscript of Book VI in the Avery Library of Columbia University, foreword by Adolf K. Placzek; Introduction by James S. Ackerman; Text by Myra Nan Rosenfeld, The Architectural History Foundation and The MIT Press, New York-Cambridge MA-London 1978.

-----, Sebastiano Serlio's Late Style in the Avery Library Version of the Sixth Book on Domestic Architecture, in «Journal of the Architectural Historians», vo. XXVIII, n. 3, 1969, pp. 155-172.

-----, Sebastiano Serlio's Drawings at the Nationalbibliothek in Vienna for his Seventh Book on Architecture,, in «The Art Bulletin», vo. LVI, 1974, pp. 401-409.

-----, Sebastiano Serlio's Contributions to the Creation of the Modern Illustrated Architectural Manual, in «Sebastiano Serlio», Sesto Seminario Internazionale di Storia dell'Architettura, Centro Internazionale di Studi di Architettura “Andrea Palladio”, Vicenza 31 agosto-4 settembre 1987, a cura di Christof Thoenes, Electa, Milano 1989, pp. 102-110.

-----, Recent Discoveries about Sebastiano Serlio's Life and His Publications», introduction to Serlio on Domestic Architecture, Dover Paperback Publications (paperback edition of Rosenberg 1978), Mineola 1996, p. 1-8.

-----, Le dialogue de Serlio avec ses lecteurs et mécènes en France dans le Sesto Libro, in «Sebastiano Serlio à Lyon. Architecture et imprimerie. Volume 1: Le Traité d'architecture de Sebastiano Serlio: une grande entreprise éditoriale au XVIe siécle», Mémoire active, Roanne 2004, pp. 153-166.

David Thompson, Renaissance Paris. Architecture and Growth 1475-1600, Zwemmer, London 1984.