Rakatansky Essay

MARK RAKATANSKY, Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, Columbia University, How Serlio Haunts Us Still: Wittkower’s Paradoxical Parallax Figure 10 Figure 20

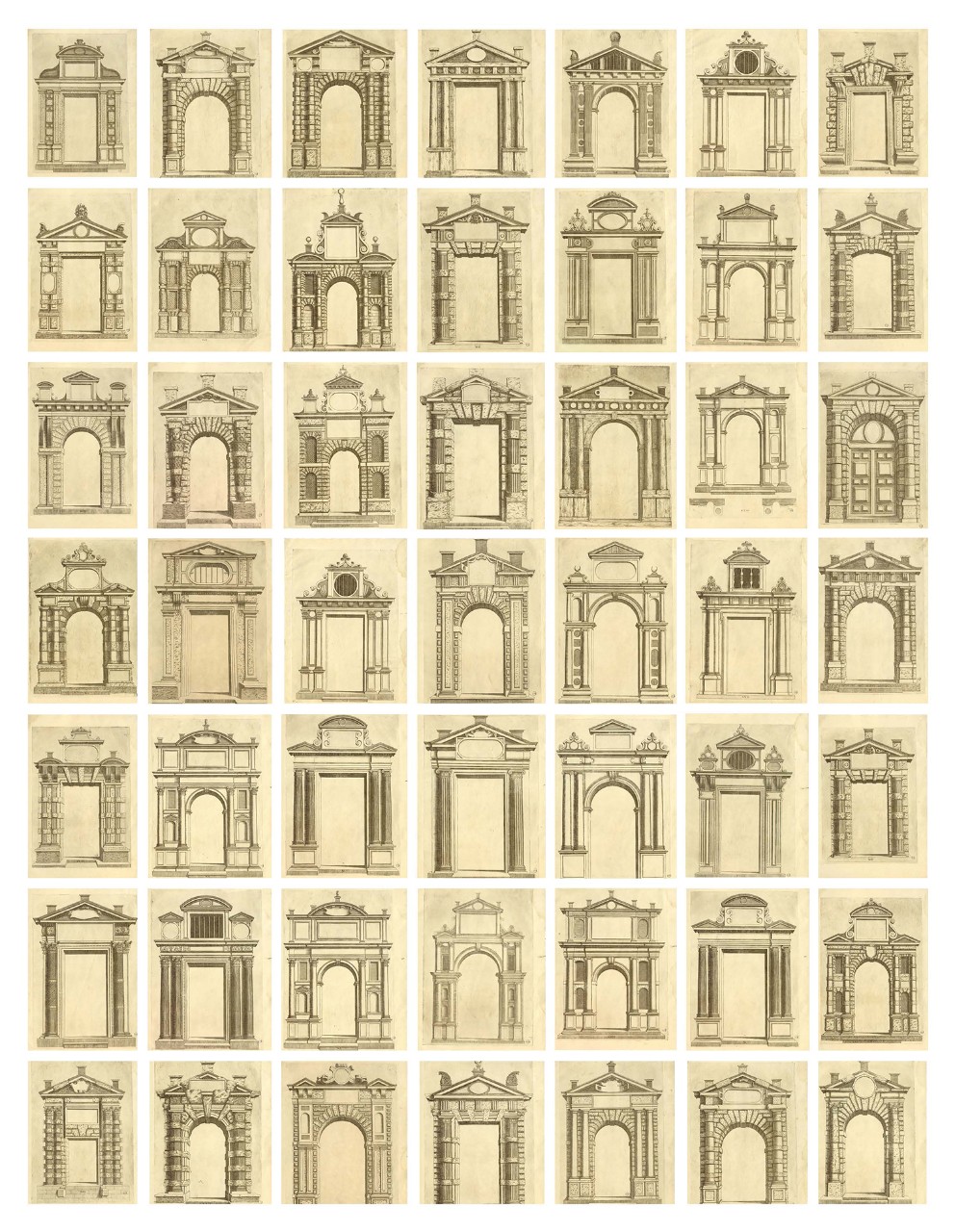

In regard to Serlio there will always be more questions than answers. Did Serlio give license to licentious rule-breaking in architecture or did he seek to normalize and contain its codes and coordinates? Did he seek to promote the Extraordinary — as stated in the title of his Extraordinario libro di architettura — or rather restrict and codify it into the now conventional and widespread all too Ordinary as a regularizing ordination? Did his professed intention to accommodate French comfort with Italian décor result not in their recombinative mixture but rather in a one variation after another of prescriptive and proscriptive commodified simulations of decorum, in other words, a catalogue of fixed social rankings of “proper” comportment? Is it he, and not Palladio, who is principally responsible for initiating the process by which certain intricate Cinquecento modes and motifs became, in Rudolf Wittkower’s phrase, “legalized and academically petrified?”1

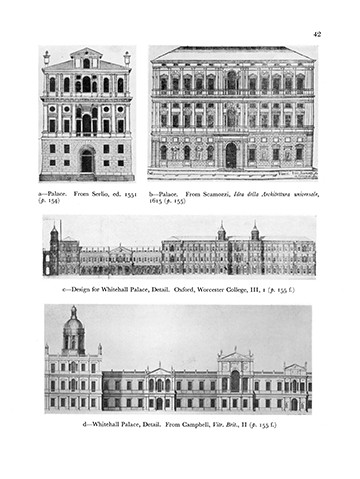

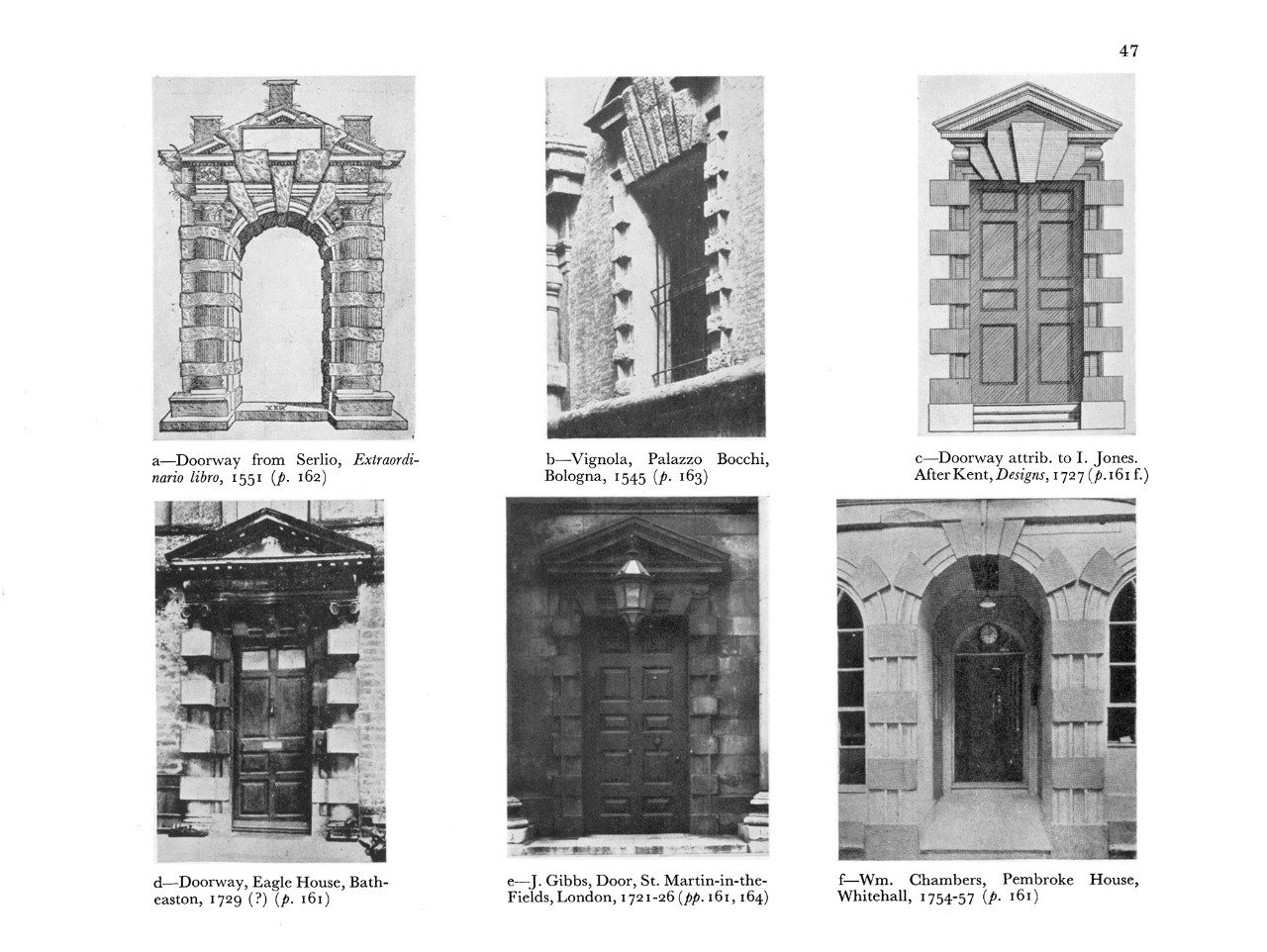

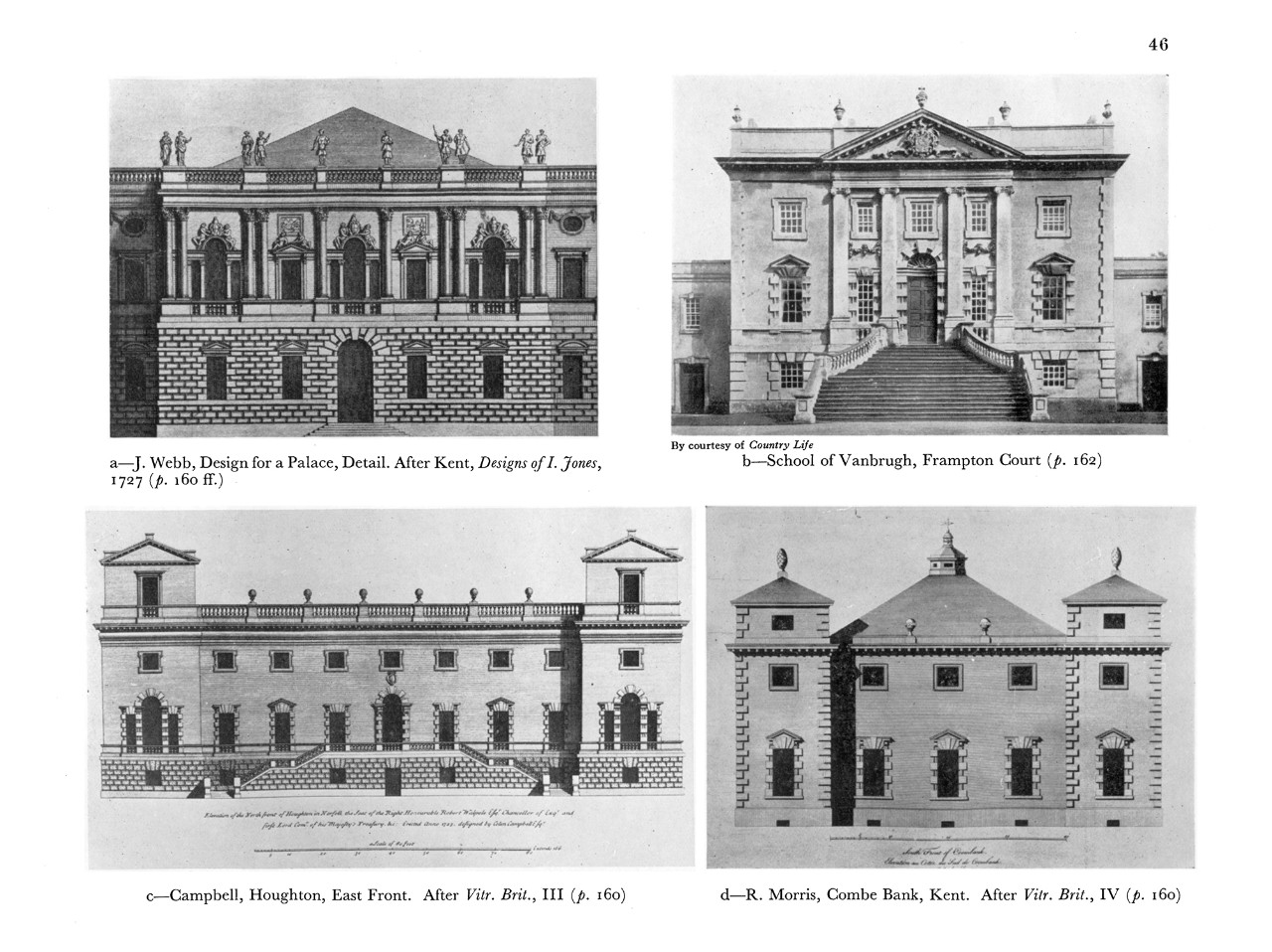

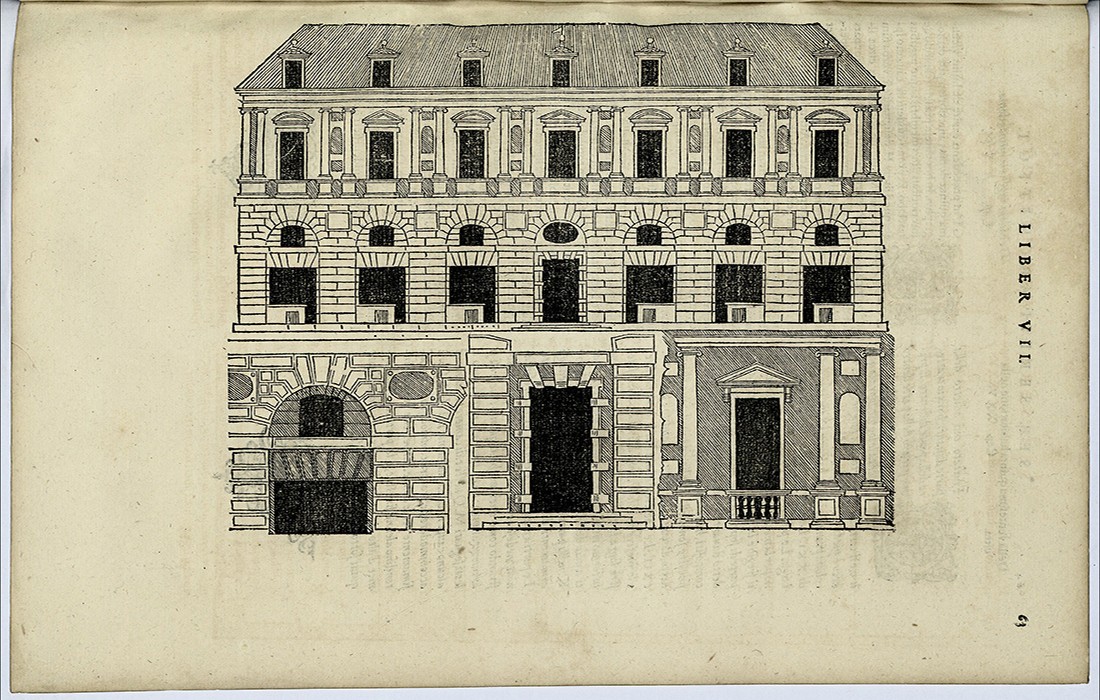

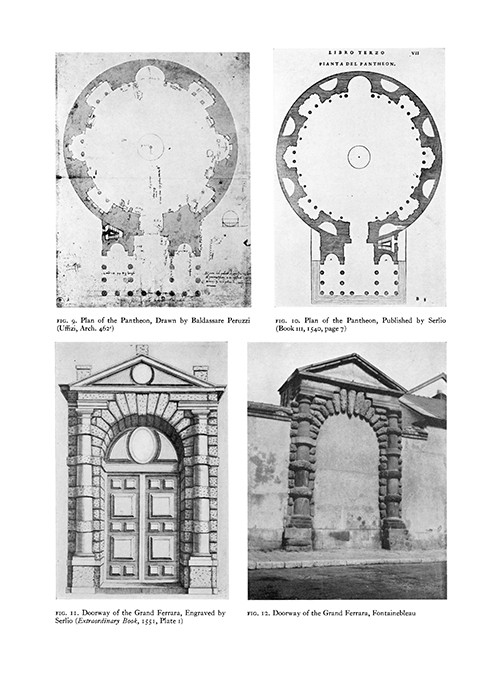

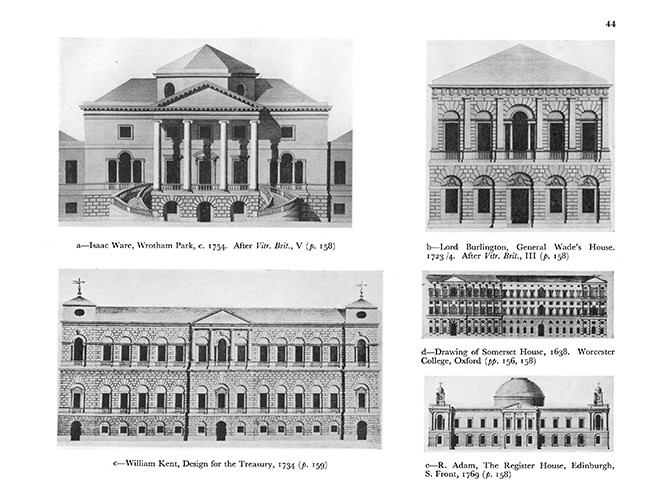

Wittkower used that phrase in his essay “Pseudo-Palladian Elements in English Neo-Classical Architecture,” wherein he tracks the developments of two Cinquecento motifs in later centuries: the “Palladian” window and the combinative tectonic figuration of quoins and voussoirs superimposed on frames of doorways and windows. Why does Wittkower refer to these elements as “Pseudo-Palladian?” First, because Palladio used the former motif only in a very limited number of instances, and the latter motif not at all. Second, because the neo-Palladians analyzed by Wittkower used the former motif in ways contrary to the ways Palladio utilized them. Third, because, in terms of published citations, these motifs were published first by Serlio in his Fourth Book in 1537 and his Extraordinario Libro in 1551 prior to the publication of Palladio’s Quattro Libri in 1570. And finally, and similarly, these motifs originated as references in England first through the publications of Serlio.

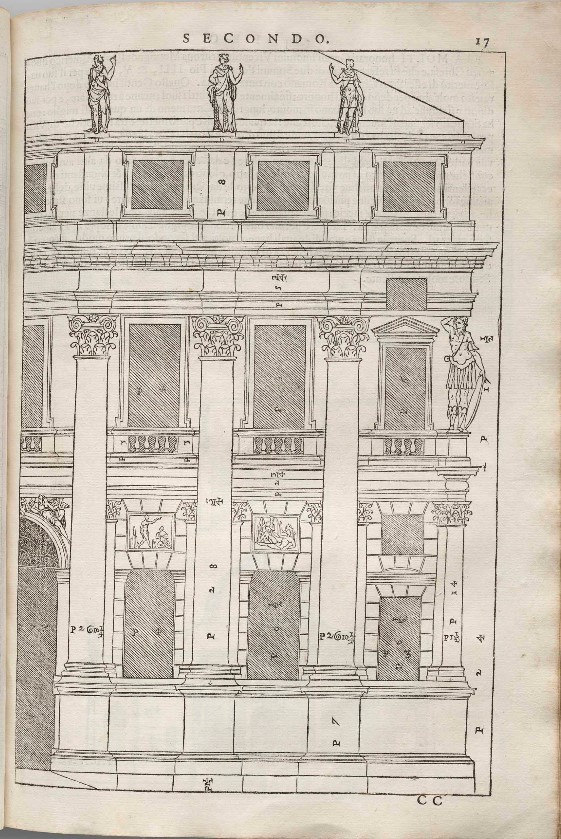

Regarding the so-called Palladian or “Venetian” window — referenced now as a Serliana not because Serlio was the first to produce this motif but because he was the first to re-produce it — Wittkower stated: “In the Basilica, as well as in the Villa Angarano, Palladio was influenced by Serlio who in the fourth book of his Architecture, published in Venice in 1537, prominently illustrates the motif in the form of a gallery and also as a window in a house front (Fig . 1).”2 And regarding the use of rustication in door and window frames, Wittkower stated, “Was this important motif really taken from Palladio? The answer is no . . . . We find this motif among the works of . . . Giulio Romano, Vignola, and, above all, Serlio,” indeed it was the “last who, in his work on architecture . . . published three gateways with variations of the motif”3 (Fig. 2)

This latter conduit of knowledge should not be surprising, as the publication of Serlio in England preceded Palladio by a century, with Serlio’s Books I-V being published by Robert Peake in 1611, while complete editions of Palladio did not appear until Giacomo Leoni’s edition in 1715-1720 and Issac Ware’s edition in 1737.4 In his “English Literature on Architecture,” Wittkower two decades later would note the extensive influence of Italian architectural theory in England, starting with Serlio:

The series begins with the Serlio of 1611, translated by the publisher Robert Peake from the Dutch edition of 1606, which was a translation from the Flemish edition of 1553, which in turn depended on the Venice edition of 1551. In spite of Serlio’s great influence on English architecture of the seventeenth century, there was no other edition. And there was nothing else for forty-four years!5

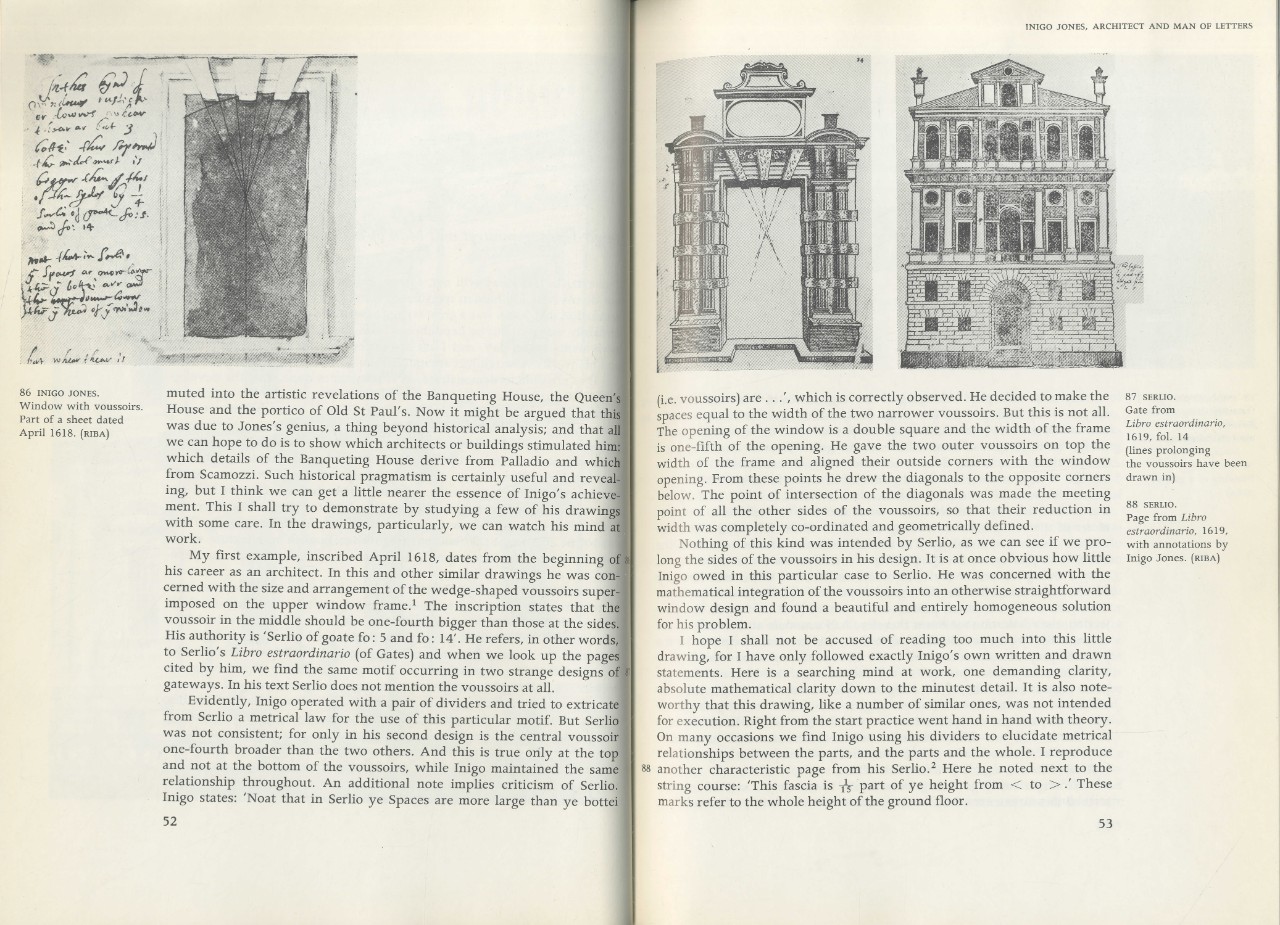

In answer to the question “Was this important motif really taken from Palladio?,” Wittkower credits William Chambers mis-crediting Inigo Jones with its invention, as a way of noting that Jones was the architect who imported it into English architecture, further noting later in the essay that Jones “possessed a Serlio” — a point he would return to in his 1953 essay “Inigo Jones, Architect and Man of Letters,” wherein he detailed the critical textual notations and visually corrective transformations Jones made regarding Serlio’s conception of the motif in the Extraordinario libro6 (Fig. 3).

Indeed given the extensive global transmission of these motifs, one might just as well speak of “Pseudo-Serlian Elements in Most Anywhere Neoclassicism.” But perhaps the “Pseudo” prefix is redundant, as Serlian elements are already, as generic pattern-book figures, simulations of virtual architectures, in other words, already geared toward simulacra. The process by which this occurs is suggested by Wittkower’s reading of their development — an evolution or a de-evolution depending on your point of view — in seventeenth and eighteenth century England. According to Wittkower, these Neoclassical architects “had no eye for the intricacy of the motif and saw in it a decorative pattern which could be advantageously employed to enliven a bare wall.”7The telling word here, the key descriptor, is “intricacy,” whose Latin roots denote the attribute of entanglement. In the case of Wittkower’s chosen motifs, this process can be characterized more broadly as one in which certain Cinquecento elements that were developed as tectonic figures within an intricately entangled and synthetic field became un-entangled from their associatively enmeshed multi-layered and interrelated network, resulting in isolated figures placed on or in the bare surface of a single-layer façade. Or if the latter were composed of two or more layers, rather than intricately enmeshed, they would be additive uniform single-layers lacking the complex interplays within and between layers that Wittkower had associated with the Cinquecento (Figs. 1, 4). And thus Wittkower’s use of the word “advantageously” in this context is not approbative, but rather indicates a casualness that reduces the complexity of the original usage, with the result that the motif appears “from a functional point of view, as a casual element, and not necessitated by the structural logic of the building itself.”8 I would propose that that casualness has its roots in Serlio, that it is evident throughout his work, and as such that it would influence Wittkower to more acutely and demonstratively position Palladio, in his later writings, at a far remove from Serlio.

Francesco Benelli has stated that Wittkower’s essay foreshadowed “the studies on Palladio that would appear in the following two years,” studies that comprised the main body of his Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism, while Summerson has proposed the essay as Wittkower’s “first assault on the muddled vaporings which passed for architectural history in England between the wars.” Summerson characterized Wittkower’s mode as enacting an exacting and crucial shift in historiography: “This kind of analysis, with its surgical dexterity and refinement, was a revelation at the time.” 9 In the essay, Wittkower associated Serlio with Giulio Romano and other non-casual Cinquecento architects in opposition to those later English architects: “The form of the motive used in England was, of course, far removed from the highly personal interpretations of Giulio Romano, Serlio and Giacomo del Duca. It was legalized and academically petrified.”10 But notwithstanding that in the works of Serlio these originary motifs may have preceded Palladio, six years later Wittkower’s re-assessment of the former in Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism was brief and pointed: “Serlio’s work is pedestrian and pragmatic, consisting of a collection of models rather than expressions of principle.”11

In fact, after the “Pseudo-Palladian” essay, Wittkower sets Serlio at such a far remove that he is almost entirely removed from Wittkower’s inquires, cited so rarely that he is nearly a phantom figure. But I would propose that tracking the phantom ways Serlio hauntingly emerges and disappears through the early drafts, the early published versions, and the final texts of Wittkower’s essays and books may help us perceive the calibration and re-calibration of Wittkower’s analytic acuity noted by these commentators, which is turn may help illuminate the seemingly contradictory modes in Serlio’s work, as well as the seeming contradictions in Wittkower’s positions. These appearances of contradiction may be understood as a form of paradoxical parallax, a shift of view that can reveal a greater depth in the perception of the figure being viewed (Serlio) as well as the figure viewing (Wittkower). The latter as much if not more so, as it might certainly seem that it is Wittkower’s shifting points of view on Serlio’s work that is the focus here, although it will be through re-viewing his lenses that critical considerations of Serlio’s work and its lingering legacy will keep emerging.

Sebastiano Serlio: Mannerist?

What will be suggested here, in regard to these apparitions, is why and how Wittkower positions Palladio between Serlio and Serlio — that is, between the mannerist Serlio he initially proposes in the essay and the pedestrian pragmatist Serlio he dismisses in the book.

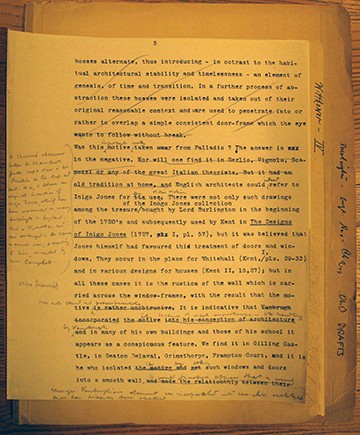

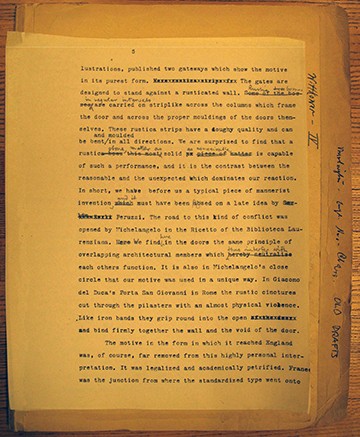

Even in the early drafts of the essay, Serlio — in the narrative and on the page — keeps disappearing only to emerge again. To that rhetorical question regarding the second motif of superimposed frames, “Was this important motif really taken from Palladio?,” after stating “The answer is in the negative,” in an early draft Wittkower had first written (and then struck-through) “Nor will one find it in Serlio, Vignola, Scamozzi or any of the great Italian theorists. (Fig. 5)”12 In this draft, as in the final text, Wittkower will correct this oversight two paragraphs later. I cited a portion of the final text earlier, but here is the complete passage, as published in England and the Mediterranean Tradition, slightly but significantly revised from its initial publication in the Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes one year prior:

We find this motif among the works of other pupils and followers, Giulio Romano, Vignola, and, above all, Serlio. The last who, in his treatise on architecture, popularized many of Peruzzi’s ideas and even used his master’s drawings for his illustrations, published three gateways with variations of the motif. They are designed to stand against a rusticated wall; rustic bosses at regular intervals are carried like bands across the columns which frame the gates and across the moldings proper of the doors themselves. These rusticated strips have something of the quality of dough and look as if they could be bent and moulded at will. We are surprised to find that rustic bosses — the most solid matter conceivable — should be capable of such a performance, and the contrast between our rational experience and the unexpected sight makes us uneasy. In Giulio Romano’s Palazzo Giustizia at Mantua the ground-floor is rusticated at irregular intervals with smooth and rough bosses, interlocked with window and door frames, and gives the impression of a work deliberately left unfinished, or interrupted before its completion. In short, we have before us in Serlio’s and Giulio Romano’s designs typical instances of mannerist invention.13

In the early drafts and the two published versions, this apparently intricate motif of a layered interlocked co-incidence of two tectonic elements is narratively expressed by Wittkower through an authorial performance of puzzlement (“We are surprised to find . . . . the contrast between our rational experience and the unexpected sight”), but what is notable in the final published version, in addition to the shift with reference to Serlio from “work” to “treatise,” is the addition of a telling three-word phrase, to wit, that this un-pragmatic tectonic performance “makes us uneasy.”

I will return momentarily to the unease Wittkower felt first on behalf of — and later with —mannerism, but first it should be noted the unease in his drafts on behalf of, and later with, Serlio. One prominent example occurs in an early draft wherein the concluding sentence of this specific passage reads: “In short, we have before us a typical piece of mannerist invention, and it must have been based on a late idea by Ser-lio Serli Peruzzi,”14 with the two instances of Serlio struck-through and x-ed out in pencil and typescript, even if in the first instance the end-half of Serlio hovers inexplicably above the typed line (Fig. 6). This double attempt at exorcism does not hold, and in the two published versions of this sentence Peruzzi disappears and Serlio reappears, as one of the two prime designers of this typical mannerist invention. Even though, in fact, Giulio Romano never used this motif — as Wittkower mistakenly accepted Adolfo Venturi’s attribution for Palazzo di Giustizia, now understood to be designed by Antonio Maria Viani half a century after Giulio’s death — leaving, by these lights, Serlio as its sole inventor.

An even more significant unease regarding Serlio manifests later, in Wittkower’s initial instance of emphatically distancing Palladio from Serlio, evidenced as a single sentence in a brief footnote in Architectural Principles: “Dalla Pozza, Palladio’s most recent biographer, stresses unduly Serlio’s influence.”15 But the original version of this footnote, published one year after the “Pseudo-Palladian” essay in the first of two Palladio essays that were incorporated in the book, provides more elaboration and puts a finer point on the matter: “Dalla Pozza, Palladio’s most recent biographer, stresses unduly Serlio’s influence . . . The thesis that Serlio was ‘la fonte non esclusiva ma essenziale della cultura del Palladio; dominante e determinante, nel processo formativo della sua conscienza artistica’” — a phrase that may be translated: “the non-exclusive but essential source of the culture of Palladio; dominant and determinate, in the formative process of his artistic conscience” — “seems to us wrong and many of his proofs for it appear unconvincing.”16 But it may be said, with regard to Wittkower’s intense reaction to what he considered as dalla Pozza’s unduly stressing Serlio’s influence on Palladio, that for Wittkower, Serlio — as a representative first of mannerism and then of pragmatism —became a non-exclusive but essential source against which he formulates the culture of his Palladio, and thus may be revealed as one dominant and determinate factor in the formative process of Wittkower’s critical consciousness.

Indeed, it is in the perceived transition from mannerism to pragmatism, or perhaps it may be said to pedestrianism, that Serlio becomes the conduit for Wittkower of what he will term the dry “academic and linear classicism” that develops later in the sixteenth century and will continue into the following centuries in Italy as well as in the England. To affect this transition of Serlio’s valance, just one year after the publication of “Pseudo-Palladian Elements” in that first Palladio essay “Principles of Palladio’s Architecture,” Serlio has disappeared as a mannerist reference, even as a principled one. The list still includes Giulio Romano, but now additionally cited are “Sansovino, Sanmicheli, Ammannati, Dosio Alessi, Vignola.”17 Serlio in this regard is cited in one brief footnote, uncharacteristically characterized in a reactionary light. Having stated in the text that at Palazzo Valmarana, Palladio deploys inversive projections in the entablature of the higher and lower orders, and that a “similar inversion can be found in an example of ancient ‘Mannerist’ architecture, the Porta de’ Borsari at Verona, which was well known to Palladio,” Wittkower foot-notes that “It is interesting that Serlio in his 3rd book commented upon the Porta de’ Borsari as being licentious and a ‘cosa barbara.’”18

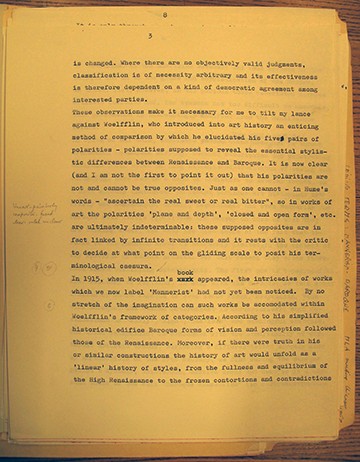

Regarding what Wittkower proposed as the principle of inversion in mannerist architecture, he self-cites from a decade prior what remains one of the most incisive accounts of such techniques in “The Ricetto and the Problem of Mannerist Architecture” section of his 1934 essay “Michelangelo’s Biblioteca Laurenziana.” The problem then for Wittkower regarding Mannerism was alluded to in a brief footnote in this essay that both acknowledged Heinrich Wölfflin’s perception of an incessant movement in Michelangelo’s architecture and critiqued his inability to “see that this movement is essentially different from that of the Baroque.”19 Decades later in 1967, in his (unpublished) address to the Modern Language Association conference titled “Critical Terms: Mannerism, Baroque,” he would recount the task he felt required at that time, a task that made “it necessary for me to tilt my lance against Woelfflin” (Fig. 7):

In 1915, when Woefllin’s book appeared, the intricacies of works we now label ‘Mannerist’ had not yet been noticed. By no stretch of the imagination can such works be accommodated with Woelfflin’s framework of categories. According to his simplified historical edifice Baroque forms of vision and perception followed those of the Renaissance. . . . In actual fact, however, in all periods there co-existed diverse artistic currents and, for reasons not to difficult to assemble, this phenomenon is increasingly manifest from the Renaissance onward.20

In spite of having attempted in the “Biblioteca Laurenziana” essay to link the intricacies of Michelangelo to mathematical and linguistic principles of permutation,21 by the first Palladio essay, “Mannerism” for Wittkower changes from being a disciplinary problem due to its lack of recognition to now being a problem in and of itself, as Wittkower refers, literally, to “the problematic architecture of Michelangelo” just four paragraphs after he had referred to his “problematic style.”22

Thus, if Serlio needed to be distinguished from certain mannerists, so it seems now, for Wittkower, did Palladio. The problem now for Wittkower is how to reconcile the apparent divergent appearance of both mannerist and pragmatic sides in Palladio’s work. For if it would seem that Wittkower laments in the work of the Neo-Palladians the loss of the intricacy that was present in what he considered the mannerism of the Cinquecento, it should be noted that the Latin root intrico, in addition to denoting entanglement, denotes as well the unease of perplexity and embarrassment. As in the prior example of the second motif in “Pseudo-Palladian Elements,” a decade hence in Art and Architecture in Italy 1600-1750, Wittkower will convey this linguistic link when he states that in “‘Mannerism’ . . . it is not uncommon that deliberate physical and psychic ambiguities puzzle the beholder. . . . the intricacies of handling are often matched by the intricacies of content.”23 Even more poignant and pointed in this regard is his statement regarding Palladio’s most intricately layered palace, Palazzo Valmarana (Fig. 8), in the first Palladio essay, reprinted verbatim in Architectural Principles, that “Language and patience have limits when describing a Mannerist structure.”24 In terms of pages and patience, his insightful section in the book addressing the mannerism of Palladio exceeds in length and language nearly all his other Palladio sections. If this statement is not an expression of Wittkower’s own perplexity and embarrassment with regard to Mannerism, then he certainly expresses (or rather performs) perplexity at its appearance in late Palladio — “The contradiction inherent in this combination. . . .the extremely complicated interplay of wall and order . . . One of the strangest characteristics of this front is the horror vacui . . . . their calculated interlocking makes the ‘reading’ of such a façade no easy matter” — and seems embarrassed enough on Palladio’s behalf to explain away these instances and almost all others — at Palazzo Thiene, Palazzo Valamarana, the Loggia del Capitanio, and the churches respectively — with recourse to precedents from Antiquity. In other words, with precedent as principle, Palladio can be exempted from the accusation of capriciousness, and thus if in the first article and the first book edition Wittkower stated that “In contrast to Michelangelo, Palladio’s mannerism is academic,” this statement is elaborated in later editions as “in contrast to Michelangelo’s deeply disturbing Mannerism, Palladio’s is sober and academic.”25 But already in the first article, Wittkower seems deeply disturbed by less “sober” forms of mannerism:

In spite of such Mannerist factors as conflict and complication, we find in the building [Palazzo Thiene] neither Michelangelo’s extreme tension, nor Giulio Romano’s almost pathological restlessness; it is orderly, systematic and entirely logical, and one looks at it with a disengaged curiosity rather than with the violent response which many more complex Mannerist structures evoke. And let it be said, all its details had the warrant of classical prototypes.26

This may seem quite a surprisingly violent non-scientific response by Wittkower to mannerist structures, this using the universal “one looks at” to claim that violent responses are what more complex mannerist structures evoke — rather than provoke, for some, which they certainly have, as they have now for him in this passage.27

In other words, in spite of titling his lance against Wölfflin, Wittkower retains some sense of the former’s psychologizing basis by assuming emotional responses in the viewing subject rather than describing visual attributes of the object (which indeed he did as well), however culturally and historically relative both may be — as he would go on to indicate in his unpublished notes to a lecture on “Mannerist Architecture” that he prepared for his Harvard University course in 1955 (Fig. 9), one year before he would arrive at Columbia University:

Mannerist structures are unstable and problematical. Instead of a soothing effect of a Renaissance building a state of suspense is evoked in the observer ranging from curiosity to uneasiness, tension, depression and conflict (Characteristic that our own time has discovered and is able to appreciate Mannerist tendencies in architecture).28

There is also quite a bit of irony in the fact that while Wittkower is wrong again in this second Giulio Romano-related mis-attribution, to which the principle design of Palazzo Thiene is now credited, he is correct to the extent that Palladio’s own description of Palazzo Thiene is pragmatic in a dull pedestrian manner.29 It may well be that in this way Palladio is covering hisembarrassment over his concealment of Giulio as the originating architect — leading historians centuries later to acknowledge what Inigo Jones recognized as obvious back in 1614 — or of the quite unconcealed mannerist details still maintained in the palazzo that had emanated from Giulio, whose influence would return in Palladio’s late work in a return of the repressed. In that regard, the co-relational incidence of the early Palazzo Thiene being positioned next to the late Palazzo Valamarana in Book II now hardly seems a coincidence, in the sense of being at all surprising. Maria Beltramini has proposed that “Palladio was almost certainly aware of the contents of Serlio’s books on residential architecture, i.e. the Sixth Book (never published) and the Seventh Book (posthumously published in 1575)”30 — and it seems that among the lessons Palladio learned from Serlio are some of the most unforthcoming ones, as in Serlio constantly curtailing his text by repeating his fear of being prolix. Indeed in his description of Palazzo Valmarana — the building as mentioned in regards to which Wittkower claims to lose patience and language — Palladio was even more taciturn than usual, not even providing Serlio’s requisite realtor tour of the building, even ending his (in the original) five withholding sentences with the single instance regarding a specific building in Book II of that most annoying interruptus phrasing straight out of Serlio: “I have said enough about this building since, as with the others, I have included the dimensions of each part.”31 On the contrary, his notsaying enough put Wittkower in the uneasy position of having to say moreabout this intricately uneasy building. And thus it may be stated that it is not in spite of but because Serlio haunts Palladio that Wittkower seeks to emphasize their distance.

In terms of embarrassment about what, or who, could be considered as overly intricate, it is Serlio, in his Extraordinary book, who, in the two prefatory letters of the book, expresses this sentiment, first to his longed-for patron “the most Christian King Henri” (with whom he hoped, without success, to remain in the good graces in terms of patronage) and “To the Readers.”32 To the King, he recounts that the intensive interest in the gateway he designed for the Cardinal of Ferrera, Ippolito d’Este, lead him to be “almost carried away by an architectural frenzy . . . . sensing as I did that my mind abounded in new fantasies” to design the series of gateway and doorways contained in this volume.33 To the Reader, he begins the first sentence by trying to explain “why I was so licentious in so many things,” blaming it on the caprice of patrons who want “new things” or their coat of arms, texts, bas-reliefs or busts, that caused him to “stray into such licentiousness, often breaking an architrave, frieze and also part of a cornice, but nevertheless using the authority of some Roman antiquities.” And in his concluding sentence he ends by supplicating: “But you, O architects grounded in the doctrine of Vitruvius (which I praise to the highest and from which I do not intend to stray far), please excuse all these ornaments, all these tablets, all these scrolls, volutes and all these superfluities, and bear in mind the country where I am living, you yourselves fill in where I have been lacking; and keep well.” Earlier in this address he lists all the other architectural elements he broke, Serlio then assures the reader that they can all be easily made whole again: “Once all these things have been removed and the mouldings where they are broken have been infilled, and the unfinished columns completed, the works will be left intact and in their initial form.”34 Thus in his confused embarrassment about intricacy, Serlio makes it clear that in fact these motifs are not interwoven, that they are indeed superfluous and can be easily added or removed, in what may be termed a casual mix n’ match manner. Nor, in terms of the media of their presentations, are these architectural elements the mixture of image and text that was one of the heralded innovations of Serlio’s books. In this last book published in Serlio’s lifetime, each of these doors and gateways are isolated figures, isolated from the field of their façades and from their textural descriptions — they are not presented as synthetic mixtures, neither in and of themselves neither within an intricate layered architectural wall nor within a layered graphic page, multiplied in an interchangeable manner as in a mercantile catalogue (Fig. 10 animation). Regarding mixtures, in his Book IV Serlio extolled Giulio Romano’s mixtures of rustic elements with the classical orders— “Rome in many places bears witness to this, as does Mantua in the most beautiful palace called Il Te . . . a true exemplar of architecture and painting for our times”35 — yet Serlio never took Giulio’s example of positioning these figural mixtures (both in Rome and in Mantua) always as transformative figurations within a multi-layered intricate field, rather than isolated figures in a bare wall. This may explain why when Manfredo Tafuri referred to the mixtures, deformations, and linguistic innovations of Serlio, he placed the word “mixtures” in quotation marks.36 These figures could be called combinations without consequences were it not the case that the consequences of their casualness still haunt us.

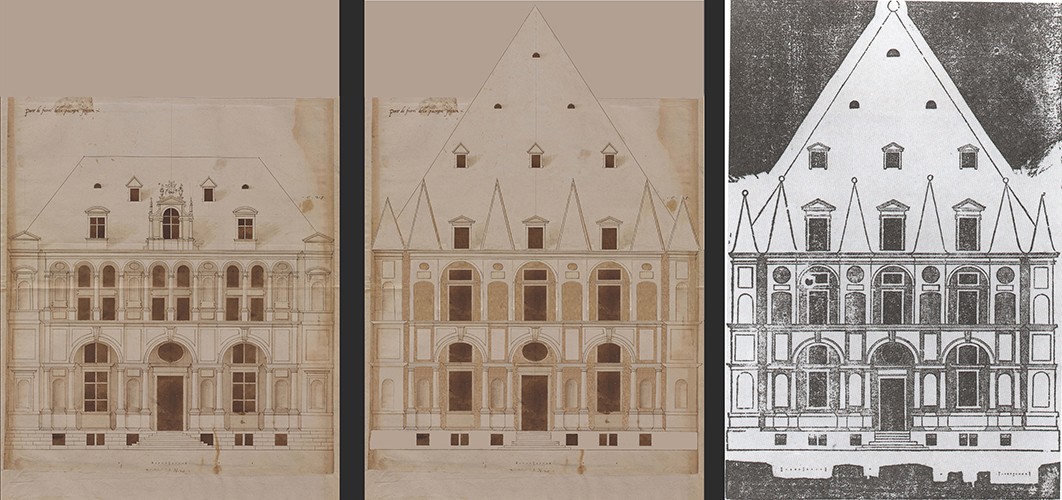

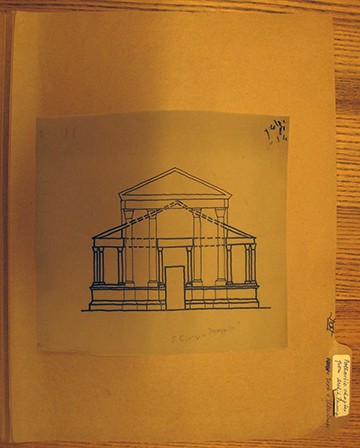

It is easier now to see in retrospect the isolationist attitude and attributes throughout Serlio’s work, the rustic doorways and gateways remaining as separated and separating figures in all the many cases where they are not just merely conventionally incorporated into a uniformly homogenous uni-layered rustic façade, in other words, not the intricate formations Wittkower had noted. Even in the sole instance in which Wittkower’s second motif of quoins and voussoirs superimposed on a door frame, is shown in the context of any entire elevation — “Habitation Inside the City on a Noble Site, the Twenty-Fifth” (Chapter XXV in Book VII), Serlio’s seven bay variation on Bramante’s Palazzo Caprini — the close-up detail Serlio includes reveals that this door is both isolated from, and its superimposed quoins proportioned out of register with, its flanking rusticated coursing (Fig. 11).

These elements of Serlio are pragmatically already-ready-made, as it were, and is, and will be, to be produced and re-produced. As long as there are — and there are still — Neo-Neo-Palladians. Extraordinary doors in pragmatically ordinary walls, a casual mannerism: how to attire your palazzo in the manner of the “mannerism” of Casual Fridays in the corporate business world, those occasions wherein you are given the license to be licentious, prescriptively and proscriptively “allowed” to dress “down” from formal business-wear within a limited list of required in-formality, a “rustic” or “pedestrian” attire — currently along the lines of a designer rustication in the lower levels with designer denim — limiting and localizing any exceptions to maintain the rules, and those ruling.

Sebastiano Serlio: Pragmatist?

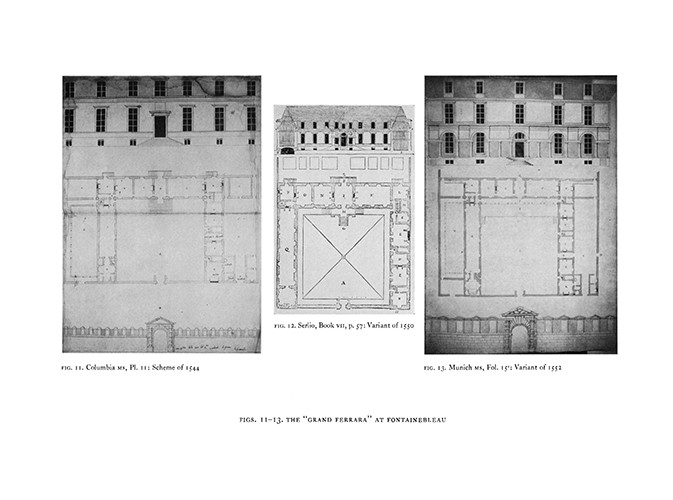

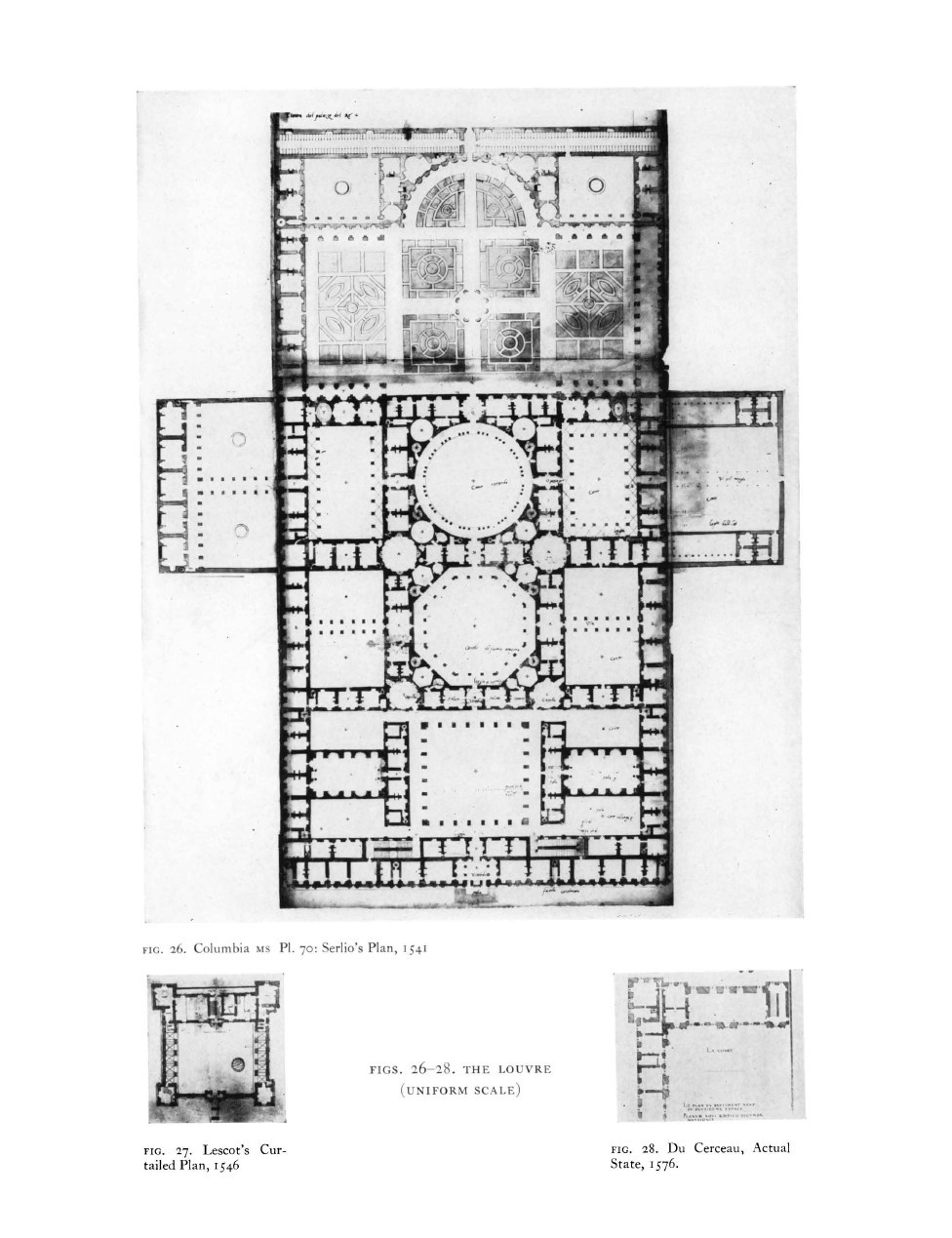

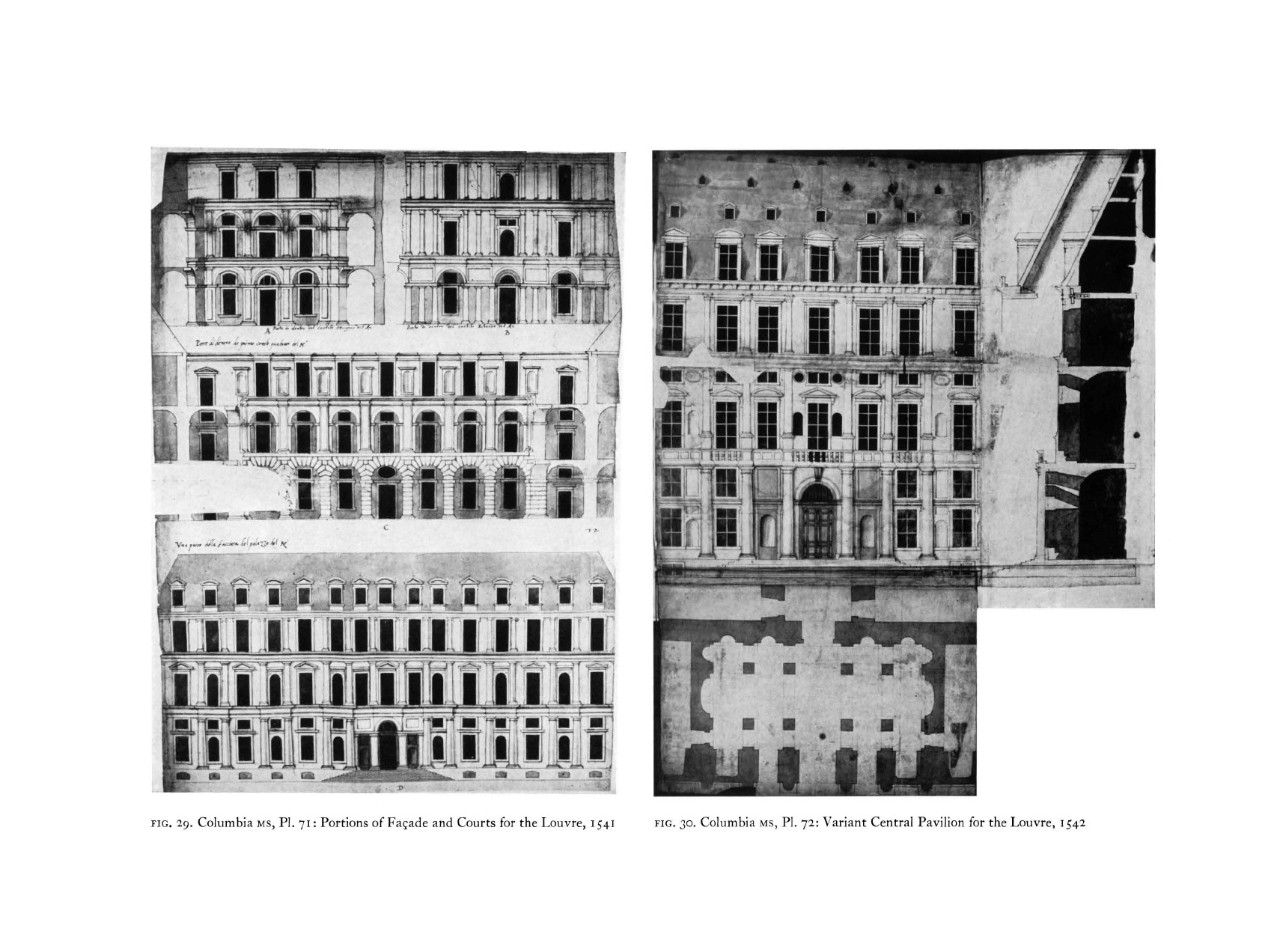

But was there a particular instigation that fostered Wittkower’s subsequent dismissal of Serlio’s work as pedestrian and pragmatic? The contiguous evidence points to Book VI, in fact Avery Library’s own Book VI, acquired by Head Librarian William Bell Dinsmoor in 1924 and described in 1942 in the two-part foundational article in Art Bulletin that Wittkower cites in the footnote to the prior sentence leading up to his castigating comment (Fig. 12).37 I said Peruzzi was edited out with reference to Serlio in the drafts of the “Pseudo-Palladian Elements” essay, but through the supportive agency and evidence of Dinsmoor, he is brought back in Architectural Principals as a way, once again, to disenfranchise Serlio: “It is well known that Serlio’s books on architecture . . . were based on material left by his great master Peruzzi. Serlio’s work is pedestrian and pragmatic, consisting of a collection of models rather than expressions of principle.”38 What aspects of Book VI conveyed in Dinsmoor’s articles may have assisted in turning Wittkower’s impressions of Serlio? In the particular article that he cites he would have seen a photograph of that Grand Ferrera doorway at Fontainebleau that Serlio says sent him into the frenzy of production that is the Extraordinario libro, and what Wittkower would have seen is that, at least in the recent state when the photograph was taken, that door was not “made to stand against a rusticated wall,” but rather had been “advantageously employed to enliven a bare wall,” decoupling it from the sense of a multi-layer intricacy (Fig. 13). A similar photograph would have been visible to Wittkower in the volume of Venturi’s Storia that he footnotes in the previous paragraph (the same volume responsible for his misattribution of Palazzo Giustizia).39 Visible in Venturi’s volume as well would have been a plate from the Munich manuscript of Book VI illustrating this doorway placed up against a rusticated wall, but Dinsmoor in the follow-up article in the subsequent issue of Art Bulletin will show both the Avery and Munich versions of this plate, with the earlier Avery version showing the doorway against a bare wall (Fig. 14).40 In either case neither wall exhibits the multi-layered puzzling intricacy that characterized mannerism for Wittkower. The other two projects Dinsmoor presents are examples of what Sabine Frommel has characterized as Serlio’s “architecture aimed at the celebration of autocratic power”41 — the Chateau at Ancy-le-Franc and Serlio’s project for the Louvre (Fig. 15) — along with projects Serlio explicitly states as designed for a tyrant, a magistrate, and a “gentleman.” Despite this apparent diversity, what is already evident in the homogenously regularized elevations shown in the article is that Book VI consisted of repetitive collections of buildings with only moderate variation, each in turn constituted out of a repetitive collection of building elements with only moderate variation (Fig. 16).

Viewed from this different angle, it may lead us, as it may have lead Wittkower, to wonder if the flatten homogenous attributes of the Neo-Palladians that he initially proposed as being contra Serlio were already manifest in Serlio’s designs. And if that is so, how then to view Palladio, with his own collection of villa upon villa upon villa? Perhaps it may be even more understandable now why Wittkower is at such pains to prove that Palladio is the principled architect such that his villa variety is not just an unprincipled pragmatic collection. In other words, why he needed to present Palladio as developing a principled Ars combinatorial (to use Tafuri’s term for Palladio’s design investigations42) in contrast to Serlio’s unprincipled collectionism. The two and a half text pages and one diagram page of the section focused on plans of “Palladio’s Geometry: The Villas,” around which so much discussion regarding Wittkower has circulated, begins in the first sentence by quoting Palladio’s Quattro Libri: “Although variety and things new may please everyone, yet they ought not to be done contrary to the precepts of art, and contrary to that which reason dictates; whence one sees, that although the ancients did vary, yet they never departed from some universal and necessary rules of art, as shall be seen in my books of antiquities.”43 In order to show that in the villas the variety is based on universal precepts, that the “grouping and re-grouping of the same [plan] pattern was not as simple an operation as it may appear,” Wittkower focuses on harmonic ratios being “at the centre of Palladio’s conception of architecture.” 44 In the follow-up article of 1945, “Principles of Palladio’s Architecture II,” which sought to explicate Palladio’s theory of ratios with respect to the villas, there is no recourse to Serlio except the statement that Palladio was aware of Francesco Giorgio’s memorandum on the proportions in Jacopo Sansovino’s scheme for S. Francesco della Vigna that Serlio had approved. And yet, when the article was transformed into the book, in a prefatory set of paragraphs added to the section “Palladio’s ‘fugal’ System of Proportion,” Serlio reappears in the guise of a prefatory not-Palladio. In the first edition Serlio’s illustration of the design of a door in his Book I is used to demonstrate the use of ratios of small integral numbers — but only as way to lead into Palladio’s Quattro Libri being “By far the most important practical system of proportion that has come down to us.”45 In the final revised version of the book, published the year of his death in 1971, Wittkower puts a much finer point on the differences and distance between Serlio and Palladio. Serlio’s “geometrical scheme is posterior rather than prior to the ratios chosen for the door. . . ‘Mediæval’ geometry here is no more than a veneer that enable practitioners to achieve commensurable ratios without much ado. But there is material at hand” — and here he hones in — “of a much less ambiguous nature.” Which is, as previously states, Palladio’s Quattro libri, now restated as “By far the most important practical guide to a coherent system of proportion known to me.”46

Practical yes, but also principled, and thus in his unpublished outline text “Renaissance, Mannerism, and Classicism,” in a section titled “THEORY AND PRACTICE,” Wittkower wrote the following note (Fig. 17): “Codification of practical experience (Serlio), of theory (Vignola), of both (Palladio). Emergence of the professional architect.”47 Serlio is positioned now to the extreme of practical experience, and thus again Palladio is positioned as being in-between, in this instance, as between practice and theory. Having distanced Palladio from the extremes of Mannerism, now it seems Wittkower needs to distance him from the extremes of Pragmatism as represented by Serlio.

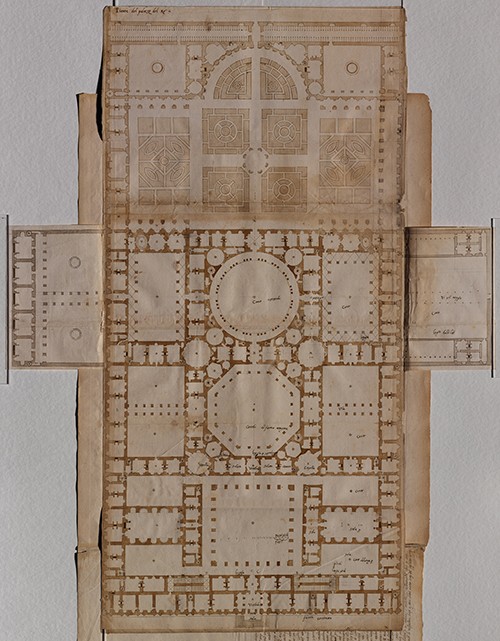

Nonetheless I would invert Wittkower’s damning statement that Serlio’s work consists of a collection of models rather than expressions of principle, not to make it any more nor any less damning, but to propose that the “principle” of Serlio’s pseudo-systematic approach is that the act of collection is his principle expression. It is in this way that his models may be said to become pragmatically pedestrian — in both the literal and figurative eighteenth-century meaning of this word to indicate the class distinction between those who have to travel by foot because they cannot afford to travel by horse (or house-drawn carriage) and something plain, dull, plodding, uninspired, lacking in vitality and distinction. Serlio’s peregrination of class distinctions in Book VI starts from the stable-less “House of the poor peasant, through three degrees of poverty” and ends with the seemingly anything but pedestrian “Palace for the King,” the penultimate sentence of which refers to its vast array of stables: “As we proceed we find two stables of considerable size and further on two large meadows for the training on horses.” This palace, Serlio’s project for the Louvre, is not only the most grandiose of Serlio’s projects in Book VI, but also its most grandiose drawing, the impressive plan of which (Plate LXXI) having elicited “oohs” and “ahhs” every time I have witnessed in Avery Library its multiple panels being unfolded to its full extension of 83.5 X 40.3 cm with its side panels extending an additional 13 cm. to the left and 12.2 cm. to the right (Fig. 18). Eliciting further, as it did every time, initially breathlessly eager but quickly abandoned attempts to count its hundreds of rooms and stables, reminiscent as they are of enough of the bloated administrative, juridical, and martial palaces of governors, kings, magistrates, princes, and tyrants — to cite Serlio’s list of prospective clients for his higher-end designs — which we have seen throughout architectural history. To that end, there seems to be a certain degree of interchangeability in this collection within certain classes for Serlio, as in the design of Plate LXV where he states “Although I have dedicated this palace to the governors, nevertheless it may be of use to tyrant princes [lhabbia dedicato a governatori : egli potra non dimeno servire agli principi tiranni].”

As for Serlio’s clients, Frommel has characterized the life of Antoine III de Clermont-Tallard, Serlio’s patron of his primary construction, the Château d’Ancy-le-Franc, as “ruled by pride and lust for power.” At the height of his political rise Antoine III had been appointed “lieutenant du roi” by King Henri II, acting “as prime representative of François de Guise, who exercised military, administrative, and juridical power in the Dauphiné on behalf of the king.”48 Frommel analyzes the château extensively, yet nevertheless concludes “The squat stories, the wide wings, the somewhat monotonous rhythms of the bays—all this lacks the dynamic impulse that distinguishes the greatest monuments of the Italian High Renaissance.”49And in regard to the Louvre project she states: “The continuous rectilinear succession of thirty-seven alternating bays without projection and recession, and without corner pavilions of the kind adopted at Ancy-le-Franc, would have given the front an even more unrelievedly ponderous and block-like character.”50

Thus while Serlio’s higher order constructed and delineated designs may appear to be far from pedestrian in the literal sense, this static monotonous ordering becomes more telling, given Wittkower’s citation of the governmental designs of Colin Campbell and William Kent for Whitehall Palace and the Treasury as examples (Figs. 1, 19), in which, within otherwise repetitive rows, motifs from the Italian High Renaissance are “conceived as isolated decorative accents . . . the Venetian window has been chosen for its decorative and festive quality and not for its intrinsic functional value . . . . Nothing can be more revealing for the character of the “Palladian” motif than the fact that here the Venetian window does not result from a particularly wide bay, and that instead of accentuating an entrance-door it stands above the unbroken sequence of ground-floor windows.”51 Those higher class autocratic and palatial models will later be developed ever more in administrative architecture, by which and in which impressive may be seen to shift to oppressive, not the least of which in the monotonous repetition, the sequences unbroken except for the occasional isolated accent. All of which will later lead to other bureaucratic palaces with their endlessly repetitive cellular organizations and figurations, from their Neoclassical (and later Modernist) repetitive windows to their repetitive bureaus (and other later forms of filing systems) which gave rise to their nomination as bureaucracies in the early 19th century.

Even with all the arrays of stables in Serlio’s projects, with even “enough space between the walls such that you could stage a good horse race there” as he says of his governor/tyrant-prince palace of Plate LXV,52 most of the large-scale designs of Serlio in Book VI or Book VII or Book VIII could be characterized as rather flat-footed, which can mean either, depending on your take and taste, firm and deliberate in an unwavering way or, as Wittkower’s “pedestrian and pragmatic” assessment implies, dull and plodding. For Wittkower it would seem that these seemingly opposite meanings are conjoined, if we can use the magnifying rear-view mirror of the neo-Palladians to view Serlio’s work, noting, as Wittkower does at the end of his essay, the processes through which those later architects literally and figuratively flattened Cinquecento motifs, elaborating on his proposition that “they had no eye for the intricate complexity of the motive and saw in it a decorative pattern which could be usefully employed to enliven a bare wall”:

This interpretation is not only supported by the fact that nowhere else have long rows of windows so consistently been treated in this manner, but also that the originally rustic quoins are always as smooth as the surrounding wall. Their functional difference from the wall is not expressed by the use of another colour or a rough surface, as in Italy. Moreover, very often the quoins are not superimposed on the frames but are on the same level with them; frame and quoins thus form a consistent surface design and nothing is left of the original Mannerist ambiguity of the motive.

It is probably not wrong to say that English academic architecture is predominantly flat and tends towards a two-dimensional reinterpretation of Italian three-dimensional elements. Italian architecture must always be judged for its plastic values; an English 18th century building should be seen from a distance like a picture.43

In this context, the concluding sentence may be restated to suggest that the elevation of an English eighteenth century building should be seen not just generally “like a picture” — there is no need for simile here — as indeed this manner of building is mediated through (and as) a picture, flattened and smoothed into a non-plastic consistency of surface design like the two-dimensional drawings, engravings, and woodcuts that fostered it.

This flattening transmission may be cited as the media-effect Serlio and other Cinquecento architects had upon these Neo-Palladians and their architecture. The loss of resolution from the fine delineation of Serlio’s unpublished manuscripts to the final rough reproduction in woodcut — evident for example in the delineated difference in Book VI between the Avery manuscript and the Printer’s Proofs in the Vienna Nationalbibliothek — may be claimed to be re-produced in and as the work of the English Neo-Palladians. Utilizing only the elements within or between levels in one of the most intricate design from the Avery manuscript, Plate XXV — the one Serlio feels required to defensively state “As I do not lack for imagination, I am going to plan a house of the same type as the last one, but with a larger variety of ornamentation”44 — we can track how its multiple layers were stripped off and the complex iterative interplay, both horizontally and vertically, in the variety and scaling of its arched, columnar, and rectilinear figurations were reduced in the spectral Vienna version to a flattened few figures that were regularized vertically and repeated (Fig. 20 animation).45 In comparison and contrast, Palladio’s encounter with print media and the burgeoning Venetian book printing industry resulted, in his late architectural work, in the interlocked and intricate multi-layered over-printing of the facades of his churches and of Palazzo Valmarana that so productively taxed Wittkower’s language and patience.

Did the loss of (graphic) resolution that was evident in his printings lead Serlio to simplify the level of complexity of his design? Or did this lack of resolution make evident a lack of resolve on Serlio’s part, given, in his recent practical experience of building, the limitations of elaboration that seemed possible or practical – that such complexity had to be regulated and relegated to limited zones like entry doorways and windows on bare walls? Or was this simplification a matter of opportunistically seeking to expand into new markets, whether the motivation may have been generated by a sensitivity to extend architectures attentions to underrepresented groups or by a desperation generated from a lack of other forms of higher stature commissions? Or merely a matter of the new style being less costly as a means to bypass artisan guilds, as in the success of certain forms of commercial Modernism or tract home development in the post war period, or say the various forms of easily reproduced commercial or residential architectures in many subsequent periods and places since this Early Modern instantiation?

Again, with Serlio there will always be more questions than answers.

Or in the age of Reformation and Counter-Reformation was this loss of intricacy a resolve to strip away superfluous complexity, as Manfredo Tafuri and Mario Carpo have each speculated?56 And was this “renunciation” based on Serlio embracing Reformist tendencies or capitulating to them? This latter question might well be asked of the 18th century Neo-Palladians, suggesting further links to Serlio, attempting as they were to bring foreign, Roman, and Catholic modes to represent the tastes of those who, as characterized by Summerson, were most disdainful of them:

Once formulated, the Palladian taste became the taste of the second generation of the Whig aristocracy . . . to which . . . artistic and intellectual leadership, once centered in the Court had passed. The second Whig generation had strong belief and strong dislikes, conspicuous among the latter being the Stuart Dynasty, the Roman Church, and most things foreign. In architectural terms that meant the Court taste of the previous half-century, the works of Sir Christopher Wren in particular and anything in the nature of the Baroque.57

And further, as Wittkower stated that Inigo Jones was the initial conduit through which certain “Pseudo-Palladian” motifs entered into England via Serlio, purifying and regularizing Serlio all the more, it may be suggested that Papal agent Gregorio Panzani’s slight against Jones as being a “Puritanissimo fiero” may indirectly point to a purposeful purification to restrict an overly evident Roman (Catholic) intricate excess, if not fully out of sight (into the privacy of “a special room with gilded and jewelled frames”) as in the case of the Italian paintings brought to the Protestant court of Charles I for his Roman Catholic Queen Henrietta Maria in the story Wittkower retells,58 but at least to the limited liminal zones and elaborated frameworks suggested by Serlio: doorways, ceiling, fireplaces, gateways and the like. This differentiation may provide some further coordinates as to why, like Serlio, the majority of the Jones's drawn building elevations are composed of reductive single line work, in comparison to his own more complex elaborations of doorways, ceilings, fireplaces, gateways, and niches.59

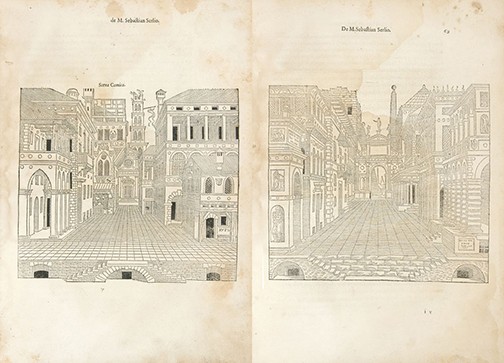

What can be stated is that similar flattening effects as those Wittkower noted in the eighteenth century Neo-Palladians — rustic quoins as smooth as the surrounding wall, quoins and wall on the same level forming a consistent surface design, their functional difference not expressed through color or texture — are represented as such in many of Serlio graphic depictions. The coursing in Serlio’s depictions are more often than not represented as single-surface single lines — in the perspective instruction plates, in the views of buildings and building elements, in the urban views of the Comic Scene and Tragic Scene (Fig. 21) — with only the occasional use of shadows, textures, or mortar joints to imply a plastic depth that Wittkower characterized as essential to intricate Cinquecento design.

If, in the “Pseudo-Palladian” essay, the academically petrified form of the motifs in England seemed far removed from the “highly personal interpretations” of Serlio, fifteen years later in his Art and Architecture in Italy 1600-1750 distance and time are now collapsed, and Wittkower will implicate and impugn Serlio in another academic petrifaction, this time in Italy in the late sixteenth century with consequences there and every elsewhere in the following centuries. In his unpublished lecture notes for his 1955 Harvard course, he will characterize this shift in the following way: “Giulio Romano’s Mannerism is more sophisticated and more playful. Palladio’s Mannerist phase is more austere. Toward the end of the 16th c. Italian Mannerism often became dry and academic and Mannerist combinations were used as stereotyped formulas. (Fig. 22)”60 Once again the specter of Serlio will haunt this transition. He is all but absent in this latter book save for a few passing citations, but there is one key moment wherein he is the key figure against which Wittkower characterizes the shift to new modes in seventeenth century Italy. It is the “dry Late Mannerism” and “frigid classicism” of Vincenzo Scamozzi (“the leading master at the turn of the century”) that Wittkower has most in mind here, whose buildings are “precursors of eighteenth-century Neo-classicism,” and whose “academic and linear classicism is, as far as plastic volume and chiaroscuro are concerned, a deliberate stepping back to a pre-Sanovinesque position. Moreover, in many respects Scamozzi’s architecture must be regarded as a revision of his teacher Palladio by way of reverting to Serlio’s conceptions.”61 To the end, the distance Wittkower established by between Palladio and Serlio is maintained still, with the latter additionally responsible more than Palladio as precursor-undercurrent for frigid forms of eighteenth-century Neo-Classicism.

The evocation of a dry late mannerist style that Wittkower believed was fostered by Serlio is used throughout Art and Architecture in Italy 1600-1750 to explain some of the aesthetic vices that certain architects and artists succumbed to or sought to distance themselves from. Two decades earlier in “Michelangelo’s Biblioteca Laurenziana,” Wittkower had contrasted the “unstable movement” of Mannerist buildings that were based on a principal he termed the “double function” — wherein a single figure seems to be associated simultaneously with two distinct entities — as opposed to the clearly distinguished “interval and order” of the “the static of the Renaissance” and “the directed movement of the Baroque.”62 While it is now clear that he would eventually favor what he considered as the more stable dynamic of the Baroque to the ambiguously instable dynamic of mannerism, yet nonetheless in Art and Architecture in Italy 1600-1750, Wittkower still felt compelled to acknowledge the incorporation of mannerist techniques to explain the aesthetic virtues of Bernini, Borromini, da Cortana, Longhi the Younger, and Rainaldi. And thus the term double function could be used to describe Wittkower’s own paradoxical parallax with regard to mannerism: “this double functional sense has the effect of confusing the divisions, as one remains undecided to which of them”63 Wittkower himself belonged.

And in regard to Serlio, if in “Michelangelo’s Biblioteca Laurenziana” Wittkower observed that “the insolable conflict, the restless fluctuation between opposite extremes, is the governing principle of the whole building,”64 what can be said here is that the apparent conflict of Serlio that Wittkower’s opposing views seem to set up will not be resolved on one side or the other. It is this parallax that provides a deeper perspective to certain attributes of Serlio’s work and their potential influence in later times, understanding that this conflict is between Serlio’s works rather than intricately within a given work as proposed by Wittkower in the case of Michelangelo’s Biblioteca. In Wittkower’s own seemingly contradictory paradoxical parallax, this dry Late Mannerism spawned by Serlio’s pedestrian pragmatism is not opposed to prior intricate Cinquecento developments, but rather represents their desiccation as a result of the isolation of motifs from their complex multilayered relations, the literal and figurative and figural flattening of their effects.

Thus if Wittkower states that in the garden front of Lord Burlington’s villa at Chiswick the “relieving arches of the Venetian windows appear here as if cut out of the flat wall with a knife,”65 then for most (if not all) intents and purposes this “as-if” simile should be discarded: these motifs from the drawing of Palladio in Lord Burlington’s collection were re-produced from Palladio’s drawing by tracing onto and cutting out from the smooth consistency of the Portland stone surfacing of that brick villa. As would be the case in innumerable other architectural instances, wherein these motifs, which were first traced into and then cut out from the flat planes of woodblocks and engraving plates of the numerous publications — those found in Lord Burlington’s library66 as well as later treatises and their popularizations — would then be traced into and cut out from other material surfacing inside and outside buildings throughout the world, most likely still being traced somewhere in the world right now as you read this.

As to the extent of this transmission, in 1584 Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo stated that Italy was full of architects who, “without any sense of their own invention . . . are at the mercy of Sebastiano Serlio, who produced more mediocre architects than the hairs of his beard.”67 What could be said today is that this statement does not nearly give Serlio his fair due, as his direct and indirect influence on architects and non-architects to date, in Italy as well as around the world, would account millions of times over what would have been the count of hairs in his beard. What does seem fair is the statement of Wittkower’s student Nan Rosenfeld, the scholar who brought Avery Library’s Serlio to full publication, in the concluding paragraph of her essay “Sebastian Serlio’s Contributions to the Creation of the Modern Illustrated Architectural Manual:”

Serlio’s books were addressed to members of every class of society from the poor dweller to the wealthy patron and to the mediocre as well as the gifted architect. The democratization of Serlio’s audience can be related to the urban revolution which occurred when the medieval feudal system came to an end and masses of the population flocked to the cities during the Renaissance. Serlio was indeed one of the first architects to understand the potential of the printed book to reach such a mass audience. If Book Vl had been printed as it was planned, the innovative contributions which Serlio brought to the printed illustrated architectural manual would be much more evident to us. The legacy of Book Vl can still be felt today in numerous magazines and manuals of housing plans available to the prospective home owner. Serlio’s methodology has survived for both the modest and wealthy home owner who wishes to build a new home without having to directly employ an architect.68

And thus a further question is posed by Serlio’s work — in paradigmatically shifting the emphasis of his architectural “treatises” from descriptive exemplars and principles of classical antiquity orientated to the highest status of client to pattern-book catalogues of example upon example upon example of his own designs (which in Book VI would claim to address all classes of habitation) — did he “democratize” architecture or lead it to the types of mass commodification of housing evident in the tract housing and McMansions found around the world as well as on newsstands throughout the United States with their monthly magazines consisting of page after page of generic Dream Home plans, widely circulating print media (Fig. 23) now nearly superseded by the even wider distributions of innumerable house-plan websites with names along the lines of eplans.com and monsterhouseplans.com? Lest this suggestion of the descent or the rise — depending on your point of view — into popular culture, this leap forward from the mid-sixteenth century to today, appear anachronistic, Serlio’s project has been characterized by Tafuri along such coordinates: “Serlio’s models, with their broad contaminations, their popularizations, and their receptivity to local dialects: they constituted an unpredictable ‘reduction’ of the universalistic pretexts of the humanistic lesson in favor of a more comprehensible language with populist overtones.”69

In his “Pseudo-Palladian Elements” essay Wittkower had already noted that the “popular neo-classical treatises on architecture recommend” the second motif of door and window frames superimposed with quoins and voussoir “almost without exception” and thus “the reason why we accept it without any disturbing reaction is not only that we take it for granted from having seen it too often, but also that in its English interpretation the conflict which it originally held, is blotted out,” footnoting that the “motive was revived in the second half of the 19th century and the streets of English towns abound with it.”70 In the same fashion, the Serliana window had been “so completely absorbed in England that it sank down from the level of ‘high art’ and was widely used as a decorative feature of popular architecture.”71 More recently Cecilia Tichi has cited this latter motif’s continued occurrence in her description of the populist overtones of the building type called McMansions, features of which have an eerie familiarity:

One real-estate writer explains the successful formula for McMansions: symmetrical structures on clear-cut lots with Palladian windows centered over the main entry and brick or stone enhancing the driveway entrance, plus multiple chimneys, dormers, pilasters, and columns—and inside, the master suite with dressing rooms and bath-spa, great rooms, breakfast and dining rooms, showplace kitchen, and extra high and wide garages for multiple cars and SUVs. Though construction quality may be subpar and materials shoddy (from faux stucco to styrofoam crown molding and travertine compounded from epoxied marble dust), McMansion buyers are eager; the real-estate writer locates them [as] . . . “mostly young, mobile, career-orientated, high-salaried 30- and 40-something individuals” who are too time-squeezed to hire an architect.72

McManors designed to appear as of the manor born, if only in an aspirational sense and sensibility. One would have to replace very few terms here to describe one of Serlio’s works, exchanging, for example, his extra wide stables housing multiple horses and horse-powered carriages for the extra wide garages housing multiple horse-powered cars and SUVs. And as for the faux stucco and moldings and marble-dust surfaces for the aspirational classes, their Renaissance roots go back to Bramante’s invention of stucco-covered brick to imitate classical rustication and the orders, which was often surfaced in marble dust to simulate stone, and which, as Cristoph Frommel has incisively noted, “. . . reduced the costs of construction considerably and made the possibilities of a direct imitation of the ancients very inviting for patrons of reduced financial means. Without this economical technique, Bramante’s direct successors—not just Raphael, Peruzzi, and Giulio Romano, but also Jacopo Sansovino, Sanmicheli and Palladio—would never have been able to achieve some of their most important works.”73 And while it would be tempting to suggest that those Cinquecento simulations could be labeled McPalazzos, their one-off instantiations and variations in this period would require, following and extending Wittkower’s narrative of the reproductive industry fostered by Serlio — and augmented by the “dry” mannerism of Scamozzi and certain neo-Palladians and certain pattern-books formulations — to develop into a different kinds of faux futures.

But the very term McMansion might even be considered a misnomer, to the extent that unlike the idealized version of McDonald’s hamburger (from which it received its name) that is supposed to appear exactly the same in franchises around the globe just like certain forms of row or tract housing — notably explored by Serlio in Plates XLVIII and XLIX of Avery’s Book VI — only someone blinded by a false connoisseurship consciousness would fail to notice the dramatically diverse variations of appearance in McMansions — however one might value or evaluate such variations, even while noting the uniformity of their social spatiality (Fig. 24). What you may notice in this search-engine screen-capture, on the bottom row, second house from the right, is that the figure of the Serliana has been taken to new or at least re-figured heights, literally and figurally, as an arcuated lintel loggia/porch with some shifted version of a “Palladian” window implied with flat frames, and even some flatten smooth quoins on the bare wall to the right, extending by a few centuries modes and motifs Wittkower had noted in eighteenth century England.

Mario Carpo has noted that in Serlio’s Book VI while the lowest and highest forms of habitation are fixed in their style (high with classical features, low without), the middle class of dwellings were “allowed” a range of possible forms and stylistic formations.74 It has been said that if you want to hear extravagant figures of speech, just go into a country market, meaning that vernacular turns of phrases often trope ordinary speech into extra-ordinary plays of language. So one could just go into the housing-market, searching for McMansions, and discover highly mannered versions of what might have been imagined as pedestrian pragmatism, as one does in the middle-classed mansions of Serlio, as much if not more as higher-classed or at least more expensive and expansive “palatial” residences today — telling in terms of a collective historical consciousness even if only rarely with a meta- or self-consciousness along the lines of Giulio or Michelangelo. Yet as a widespread phenomenon, these seemingly extraordinary outward variations of whichever class might nonetheless belie another form of mass (cultural) production, restricted and codified in master-planned communities into the now conventional and widespread all too Ordinary as a regularizing ordination — their professed intention to accommodate French (Italian / Spanish / Tudor / Craftsman / Mediterranean / Luxury / Causal / Modern / Traditional) comfort with Italian (French / Spanish / Tudor / Craftsman / Mediterranean / Luxury / Causal / Modern / Traditional) décor resulting not in their recombinative mixture — unless you believe such recent fatuous marketing denominations like “European Ranch House” — but rather in a one variation after another of prescriptive and proscriptive commoditized simulations of decorum, in other words, a catalogue of fixed rankings of “proper” comportment. These mixtures could be called casual combinations without consequences, a process I have suggested was initiated by Serlio, were it not the case that the consequence of their “casualness” still haunt us. More mixes and matches, to a large degree still isolated as architectural figures or “features” placed on or in bare walls. With regard to the cultural anthropology of these materialized matters, even the “custom” modifications available when ordering these dwellings are merely orders from the limited menu of whatever the reining “tribal” custom of the day is in terms of what may be considered as “comfort” and “décor” in its particular time period. Serlio’s menu of geometrically isolated room figures along the very self-contained lines of camera, anticamera, retrocamera, camerino, sala, saletta, passageways, loggias, kitchen, baths, dining rooms, and defensive vestibules may today be mixed and matched with safe rooms, home offices, e-rooms, great rooms, game rooms, leisure rooms, grand salons, master suites, powder rooms, and walk in closets that approach in scale certain Manhattan studio apartments now fashioned as “micro-units.” And the current claims that McMansions have given way to “Next Gen” housing, whose selling point of “flexibility” is the next generation of a desperate marketing strategy for the housing industry, dreaming up new dream homes following the burst housing bubble of recent years — “Lennar, the nation’s largest homebuilder, is developing more than 300 of the homes in the master-planned community near the Ghost Mall” — reveals just the latest version in combinationism of equivalent formations of social space:

A marketing flyer of the small kitchen table touted the potential: “Home office, separate teen suite, or a returning college student’s private pad.” . . .

If the baby boomer’s dream house was a multi-turreted McMansion with a formal living room, dining room and a three car garage, the millennial’s might be a just big-enough cottage-style bungalow with a home office, a rental unit and a carport that doubles as an outdoor living room.

Ms. Marcus Webb said the New Home Company recently had architects draw up plans for a new home design that includes just that: a flexible, L-shaped outdoor living area that could be a living room, a carport or a place to park an Airstream. “It could either be a girl cave or your guest room,” she said. “Or a place for your parents.”75

What a field-day (or field-work) for either some future architectural historian or archeologist.

Or anthropologist: to his credit, Serlio’s description of his series of rooms and their uses provides an invaluable account of historical anthropology regarding taxonomies of habitation between and within social types. And yet, Serlio as a guide conveys, for the most part, little more information than what one might hear on a tour through a McMansion or a Next Gen, merely enumerating the collection of room upon room in a codification and commodification of culture, sounding excruciatingly like a real estate agent trying to sell one of his properties.76 Which of course he is. Once again the act of collection is Serlio’s principle expression, both visually and textually. That is the re-productive agency he has provided through the centuries. And the extensive array of the geometrically elaborated plans of these prescribed rooms in Serlio’s Book VI and Book VII and the equally extensive forms of representational techniques — impressive or oppressive, depending again on your take and taste — is matched and exceed (at least in number) by the hundreds available in each House-Plan Magazine and millions available online, multiplied in an interchangeable manner in these mercantile catalogues. Seemingly endlessly varied as though carried away in an architectural frenzy like Serlio’s in his Extraordinary book, these variations, like Serlio’s, emanate from that limited mix and match menu that in spite of their evident diversity manifest globally in master-planned developments as a collective uniformity, a characteristic they share with the uniformity of administrative “Pseudo-Serlian” architectures throughout time and the world, whether in sense or sensibility. The degree to which — and the mannered degrees from which — the same geometrically and stylistically elaborated prescriptions may be observed in “truly custom” houses or institutional buildings designed by even the most noted architects in the past or present or future may be evident through a cultural (anthropological) analysis.

To that extent the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, in his book The Way of the Masks, has proposed that in transformations of motifs in the masks of different tribes, “a mask is not primarily what it represents but what it transforms, that is to say, what it chooses not to represent.” — as in, for example, an “excess” of Roman Catholic intricacy which may be imagined as something chosen not to be represented in the case of the English architects cited by Wittkower. Lévi-Strauss extends this principle to the history of successive art historical style: “The Louis XV style prolongs the Louis XIV style, and the Louis XVI style prolongs the Louis XV style; but at the same time each challenges the other.”77 We thus might hold in anthropological suspension any teleological valuation, positive or negative, of these successive manifestations of style, given that representational systems, as Lévi-Strauss noted, “cut across a complex historical flow, to which it would be unwise to assign a privileged direction.”78 Cutting across a complex historical flow between centuries, Wittkower set up a comparable perspective within the discipline of architecture with Pseudo-Palladian, aka Serlian, elements that were seemingly represented, but with certain of their attributes not represented, or rather re-presented, in the combinative and inflationary (in terms of scale) architecture of that time. Rosenfeld cut across four centuries to find not so much the style of Serlio, but the medium of his combinative and inflationary (in terms of quantity) re-production outside the discipline carrying forward the effects of Serlio into our time. I have suggested that the senses and sensibilities noted by Wittkower and Rosenfeld in these later centuries were present in the design sense and graphic sensibility of Serlio’s works, and that is the manner through which Serlio continues to haunt these “high” and “low” cases and classes of architecture. Looking four centuries forward within the discipline to those who might be said to seek to intensify these reductive effects astheir aesthetic project — we might perceive the reactive interest in flattened repetitive formations as well as populist overtones and combinationism in, say, the works of Aldo Rossi, whose citation of Serlio in his 1981 A Scientific Autobiography — “I found walking on Sunday mornings through the Wall Street area to be as impressive as walking through a realized perspective by Serlio or some other Renaissance treatise-writer” (repeated in his “Introduction to the First American Edition” of The Architecture of the City)79 — which in turn might lead us back to see such popular overtones and combinations of urban forms in Serlio’s Comic Scene and its re-mixed and re-matched contiguous Tragic Scene in his Book II, in sharp contrast to the more “principled” multi-layered urban scenes attributed to Giuliano da Sangallo in Baltimore, Berlin, and Urbino. Similar overtones of populism and combinationism, may be perceivable in the more recent polemical calls by Michael Meredith for an architectural casualness of an “indifference” (2017), for a “low-resolution architecture” (2018), many of the stated examples of which are manifest in purposely reductionist formations, in contradistinction to the kind of examples called forth by Greg Lynn in his earlier equally polemical exhibition entitled Intricacy (2003).80 With the understanding that any critical analysis of such resonances would require not the immediate assumption of any one-to-one correspondence in conceptual meaning, social context, or formal technique — even with the coincidence of certain key words, such as “intricacy,” which at times may seem to open up or to bar access to certain associations or disassociations — but rather a parallax perspective of the differences within the similarities and the similarities within the differences, each to the other as well as to other historical modes and motifs.

In that regard, it should be said that any discussion of the pre- or post-humous publications of Serlio with regard to architecture in subsequent centuries has to be understood as a virtual historical apparatus that may be useful to the degree it can assist in perceiving modalities evidenced in the works of Serlio that were available to those architects (or to historians such as Wittkower), as well as those modalities that had been disseminated through certain (Cinquecento and later) architect or non-architect practices and productions. Following this word’s etymological roots, what may be considered are whichever virtues and virtuosities and capabilities and efficiencies and virtuousness, or lack thereof, may be found and channeled by whomever finds and channels them — from mannerist efforts toward virtuosity to pragmatist efforts to make a virtue out of practical necessity. But perhaps all historical artifacts — whether constructed, represented, or written — are virtual in this way, always instigating more questions than answers, imminent in their capacities to emerge anew to haunt received historical and historiographical accounts, to provide new perspectives even though or especially because of their capacity to provide an increased perception of cultural depth due to the shift of re-cognition and registration that is the effect of parallax. The artifacts of Serlio (and Wittkower) haunt us still.

Many thanks to Francesco Benelli, Carole Ann Fabian, Teresa Harris, Lena Newman, Margaret Smithglass, Lorenzo Vigotti, Aaron White, and Yuheng Wu for their engagements with this work.

Notes

1 Rudolf Wittkower, “Pseudo-Palladian Elements in English Neo-Classical Architecture,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 6 (1943): 163.

2 Ibid., 154.

3 Ibid., 162.

4 Rudolf Wittkower, “English Literature on Architecture” in Wittkower, Palladio and English Palladianism (London: Thames and Hudson, 1974), 100. Charles Hind and Irena Murray, “Publishing Palladio and the spread of Anglo-Palladianism,” in Charles Hind and Irena Murray, eds., Palladio and His Legacy: A Transatlantic Journey (Venice: Marsilio, 2010), 110.

5 Rudolf Wittkower, “English Literature on Architecture,” 100. This text, as the Contents page states, was an “Unpublished lecture given at Columbia University, New York, May 1966).” John Summerson as well, a decade earlier, had noted that Serlio “posthumously and at long range, influenced English architecture more than any other single man,” and suggested that while, from the “English point of view,” the Venice quarto of 1566 (Books I-V and the Extraordinary Book, published by Francesco De Franceschi & Johann Criegher) was probably the most important edition, the Frankfurt edition of 1575 (which included Book VII, published by André Wechel & Jacopo Strada) “also had its effect” (Architecture in Britain, 1530 to 1830(Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1953), 24).

6 Wittkower, “Pseudo-Palladian Elements in English Neo-Classical Architecture” (1943), 162, and Rudolf Wittkower, “Inigo Jones, Architect and Man of Letters,” in Wittkower, Palladio and English Palladianism(London: Thames and Hudson, 1974), 52-53.

7 This is the slightly revised version with the same title published two years later in The Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, ed., England and the Mediterranean Tradition: Studies in Art, History, and Literature (London: Oxford University Press, 1945), 152. The original phrasing was: “had no eye for the intricate complexity of the motive and saw in it a decorative pattern which could be usefully employed to enliven a bare wall” (Wittkower, “Pseudo-Palladian Elements in English Neo-Classical Architecture” (1943), 163).

8 Wittkower, “Pseudo-Palladian Elements in English Neo-Classical Architecture” (1943), 156.

9 Francesco Benelli, “Rudolf Wittkower versus Le Corbusier: A Matter of Proportion,” Architectural Histories 3(1): 8 (2015): 4. John Summerson, “Palladio and Palladianism by Rudolf Wittkower,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 35:2 (1976): 146. These two statements are interrelated and confirm Howard Hibbard’s earlier assessment of the essay in his Wittkower obituary (“Rudolf Wittkower,” The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 114, No. 828 (Mar., 1972), 175): “The first symptom of what became a major force in his later career is the ingenious, and I believe for England novel, typological study, ‘Pseudo-Palladian Elements in English Neo-Classical Architecture’ (1943). In this article Wittkower showed how the English had transferred Italian motifs into new contexts, transformed them, and created what was really a new English style. These discoveries led both back to Palladio and forward into the eighteenth century.” For further historiographical analysis of Wittkower’s work, see Henry A. Millon, “Rudolf Wittkower, ‘Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism’: Its Influence on the Development and Interpretation of Modern Architecture,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 31:2, 1972, 83-91 and Alina A. Payne, “Rudolf Wittkower and Architectural Principles in the Age of Modernism,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 53 (3) (1994), 322-342.

10 Wittkower, “Pseudo-Palladian Elements in English Neo-Classical Architecture” (1943), 163.

11 Rudolf Wittkower, Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism(London: Warburg Institute, University of London, 1949), 17.

12 Rudolf Wittkower Papers, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Butler Library, Columbia University, box 42, envelope: “Burlington.”

13 Wittkower, “Pseudo-Palladian Elements in English Neo-Classical Architecture” (1945), 151.

14 Rudolf Wittkower Papers, box 42, envelope: “Burlington.”

15 Rudolf Wittkower, Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism(1949), 55, ft. 3.

16 Rudolf Wittkower, “Principles of Palladio’s Architecture,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 7 (1944): 104, ft. 6.

17 Ibid., 116.

18 Wittkower, Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism (1949), 77, ft. 2.