Kachina and Kokko: Hopi and Zuni Figures: Research Report by Darcy Olmstead

Fig. 1. Unidentified Hopi artist, Kachina tihu: Tasap, late 19th to early 20th century, Arizona, wood with paint, H. 12 in. (30.5 cm), Art Properties, Avery Library, Columbia University, The Bush Collection of Religion and Culture (C00.1483.342).

Fig. 1. Unidentified Hopi artist, Kachina tihu: Tasap, late 19th to early 20th century, Arizona, wood with paint, H. 12 in. (30.5 cm), Art Properties, Avery Library, Columbia University, The Bush Collection of Religion and Culture (C00.1483.342).

In Fall 2022 Art Properties received an award from Columbia University Libraries as part of its Antiracism, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusiveness (ADEI) program. This award made possible the hiring of two Columbia graduate students to study, research, and report on areas of the Native American collection in Art Properties.

Darcy Olmstead, the author of this essay, earned her MA in Columbia University's Art History, Modern and Contemporary Art (MODA) program. Darcy's report is not intended to be a definitive guide on this topic of kachina and kokko, but rather demonstrate innovative possibilities when researching Native American objects in Columbia's Art Properties collection. This educational opportunity is particularly important in our efforts toward more transparency and visibility with our Native American collections, and Columbia University Libraries' ongoing commitment to ethical stewardship and fulfillment of our responsibilities to be in compliance with the federal Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA).

Our thanks to Columbia University Libraries and the ADEI Award program for sponsoring these educational opportunities in Art Properties, and to Nancy Rosoff, Andrew M. Mellon Senior Curator, Arts of the Americas, Brooklyn Museum, for her assistance and advice with the students' research.

Kachina and Kokko: Hopi and Zuni Figures in the Art Properties Collection at Columbia University

Research Report by Darcy Olmstead, Graduate Student Assistant 2022-2023, Art Properties

The Pueblo kachina spiritual tradition, according to historian Polly Schaafsma, has existed for nearly 1,000 years in the area now known as the American Southwest (Schaafsma 2). The term "kachina" is what Hopi tribal members today use to describe masked or painted impersonations of spirits [note 1]. The term "Katsina," on the other hand, refers directly to several entities: the spiritual being itself, the clouds (another aspect of the spiritual beings), and the dead, according to Louis A. Hieb's essay "The Meaning of Katsina: Toward a Cultural Definition of 'Person' in Hopi Religion" (Schaafsma 23-33). The term "kachina tihu" refers to the dolls or figures, such as those in the Columbia University Art Properties collection (fig. 1). The supernatural being, the "Katsina," represents the spirit of a specific deceased person or embodies a natural phenomenon such as the sun, the moon, a plant, or an animal. Katsinam (the plural form of the word) are typically benevolent and convey traits such as the ability to control rainfall, or act as messengers between Pueblo villages and gods. These spirits are typically identified with the Hopi and Zuni people, each of which have their own Indigenous languages. The Zuni refer to their similar beings as "Kokko."

The Hopi and Zuni are part of the Pueblo tribal nations. The Zuni and eighteen others are based in New Mexico, while the Hopi are largely separate from the established other Pueblos in Arizona. For the Hopi, Katsinam are tied to their cosmic identity and life cycle. According to tradition, after death, one hopes to be transformed into a Katsina, a cloud spirit who ascends to the San Francisco Peaks, a mountain range in Arizona, to bestow rain and other blessings upon the living. Katsinam are typically benevolent spirits that, according to believers, visit villages between December and July through ritual incarnation via the bodies of masked men engaged in ceremonial dances. Katsinam often distribute gifts to the children of the village: weapons for the boys and kachina tihu (small figurines in the likeness of the katsina spirits) for the girls. Although this may seem like gender bias for non-indigenous people in the twenty-first century, it is based on long-standing cultural practices within the Hopi community.

Traditionally, tihu are made by men, the designated carvers and weavers of Hopi society. Tihu are seen as rewards for virtuous behavior and perceived as instructional tools for girls to preserve sacred village histories through the memorization of more than 250 different types of Katsinam. Some of the earliest surviving kachina dolls were carved from single cottonwood roots. However, after European-American collectors became interested in Katsinam in the late nineteenth century, the tihu became more realistic and dynamic, mimicking more humanistic sculptural figures and requiring the carver to use multiple pieces of wood. European-American collectors began depositing these kachina tihu in public collections, resulting in the dolls acquiring traits that made it easier for the objects to be displayed in museum settings, rather than their origins in Hopi homes.

Fig. 2. Unidentified Hopi artist, Kachina tihu: Heliki(?), early 20th century, Arizona, wood with paint and feathers, H. 9 1/8 x L. 5 1/2 in. (23.1 x 14 cm), Art Properties, Avery Library, Columbia University, The Bush Collection of Religion and Culture (C00.1483.344).

Fig. 2. Unidentified Hopi artist, Kachina tihu: Heliki(?), early 20th century, Arizona, wood with paint and feathers, H. 9 1/8 x L. 5 1/2 in. (23.1 x 14 cm), Art Properties, Avery Library, Columbia University, The Bush Collection of Religion and Culture (C00.1483.344).

Thus the carving and display of Hopi kachina tihu, like many other types of Native American objects, have a complicated history in terms of use over time. The kachinas held in the Art Properties collection demonstrate the modification of these figures from sacred educational objects, to tourist dolls and collectibles, and finally into displayed objects. All six of the Art Properties kachina tihu were acquired either by philosophy professor Wendell Ter Bush (1867-1941) in the early decades of the twentieth century, or by subsequent curators of the Bush Collection in the 1940s. Bush was known for using religious and spiritual objects from his personal collection in his lectures as visual aids, and these objects were subsequently displayed in cases in Low Library where the Bush Collection was on view. The Art Properties collection of kachinas thus unexpectedly evolved from being educational tools in Hopi communities, traditionally given to young girls to educate them about their belief system, into educational tools for Columbia undergraduates to learn about Pueblo religion.

Despite this surprising similarity in educational use, there remain many questions regarding the intentions of the makers of each of the kachinas. Were these figures carved for traditional kachina dance ceremonies and then displayed within Hopi homes? Or were they carved for the growing native art market at the turn of the twentieth century, intended to appease tourists and collectors on the East Coast? It is also possible that some tihu were carved by non-indigenous people, as this became a popular craft for predominantly European-American groups such as the Boy Scouts [note 2]. The popular 1957 book Kachina Dolls by W. Ben Hunt instructs readers on how to carve their own tihu as well as kachina-inspired ashtrays, lamps, and coffee canisters. It is, therefore, evident why debates surrounding the authenticity of kachinas have been troubling institutions for decades. The unclear origins of the dolls in the Art Properties collection demonstrate the challenges underscoring the collecting, stewarding, and display of Native American cultural heritage objects and artifacts in all institutions.

Fig. 3. Unidentified Hopi artist, Kachina tihu: Shalako or Mana, early 20th century, Arizona, wood with paint and feathers, H. 10 9/16 in. (29.9 cm), Art Properties, Avery Library, Columbia University, The Bush Collection of Religion and Culture (C00.1483.317).

Fig. 3. Unidentified Hopi artist, Kachina tihu: Shalako or Mana, early 20th century, Arizona, wood with paint and feathers, H. 10 9/16 in. (29.9 cm), Art Properties, Avery Library, Columbia University, The Bush Collection of Religion and Culture (C00.1483.317).

Many of the kachinas in the Art Properties collection are difficult to identify, and this in fact may have been intentional. According to curator Carolyn Kastner, "all ritual knowledge, including knowledge of kachina tithu, is considered a privilege among Hopi and Pueblo people and is in direct conflict with the dominant American ideology of having a right to knowledge" (Kastner 101, her italics). Because of this, many carvers have been known to change small details in kachinas before selling them to collectors and tourists. Of the kachina figures in Art Properties, one of them (fig. 2) is difficult to identify due to the object’s unique shape. Rather than a traditional stand-alone figure, this kachina is situated within a traditional Hemis (a Katsina corn deity) headdress. Traditional tihu were never created with a base. They were typically displayed in Hopi homes by a hanging thread that was tied around their neck or waist. Tihu, made so that they stand upright on their own, were created for non-indigenous collectors who wished to display them in a typical Anglo-American manner. That this object was intended for the tourist market is also indicated by the surviving price of $1.50 handwritten in pencil on the back of the object.

For other Hopi, sharing kachinas with outsiders is a means of elevating Hopi traditions and preserving their way of life. A doll known as Mana (fig. 3) appears similar to the Shalako Mana maidens in the collections of institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Brooklyn Museum, and the Dallas Museum of Art [note 3]. This figure in the Art Properties collection is definitely a maiden or "mana," due to the mantel she wears, but the exact kachina she represents is unclear. Her iconography vaguely matches illustrations of the Shalako Mana Maiden illustrated in the so-called Fewkes Codex (discussed below), but small differences suggest instead Palahiko Mana, in particular her headdress.

Fig. 4. Unidentified Zuni artist, Kokko painting: Kakali (Eagle), ca. 1930, pencil, ink, and watercolor on poster board, 7 1/8 x 8 3/4 in. (18.1 x 22.2 cm), Art Properties, Avery Library, Columbia University, The Bush Collection of Religion and Culture (C00.1483.252).

Fig. 4. Unidentified Zuni artist, Kokko painting: Kakali (Eagle), ca. 1930, pencil, ink, and watercolor on poster board, 7 1/8 x 8 3/4 in. (18.1 x 22.2 cm), Art Properties, Avery Library, Columbia University, The Bush Collection of Religion and Culture (C00.1483.252).

As noted earlier in this research report, the beings referred to as Katsinam by the Hopi have parallels in Zuni culture, where they are known as "Kokko." The Art Properties collection of Zuni Kokko watercolor paintings (fig. 4), like the Hopi kachina tihu, similarly present a complicated history with regard to both the problematic anthropological studies of indigenous groups in the region, as well as the development of Pueblo modern art. The watercolors have been kept in the Bush Collection and were long believed to have been acquired by Bush himself. However, it was recently discovered by Art Properties staff, based on research done in the 1970s and 1980s by art history professor Seymour Koenig, that many of the Columbia Zuni watercolor paintings were collected by anthropologist Ruth Bunzel, with a number of them published in a 1932 Smithsonian report. In a 1984 commercial reprint of Bunzel’s text, the editors published some color reproductions from original watercolor paintings located in the author's archive at the Smithsonian Institution. The editors noted in this reprint edition that many of the black-and-white images were untraceable, but in fact many, if not all, seem to be in the Columbia collection and had not been traced by the editors.

This discovery underscores how further research in the Bush Collection, as well as the Bunzel archive, is necessary, and demonstrates the many instances in which the collecting of Native American objects has remained undocumented and understudied. Bunzel received her BA from Barnard College and her PhD in anthropology from Columbia. She did teach at Columbia and worked as a researcher for a number of years, so it is likely that many of her watercolors were donated to the Bush Collection for research and study purposes, though more research on this provenance is needed.

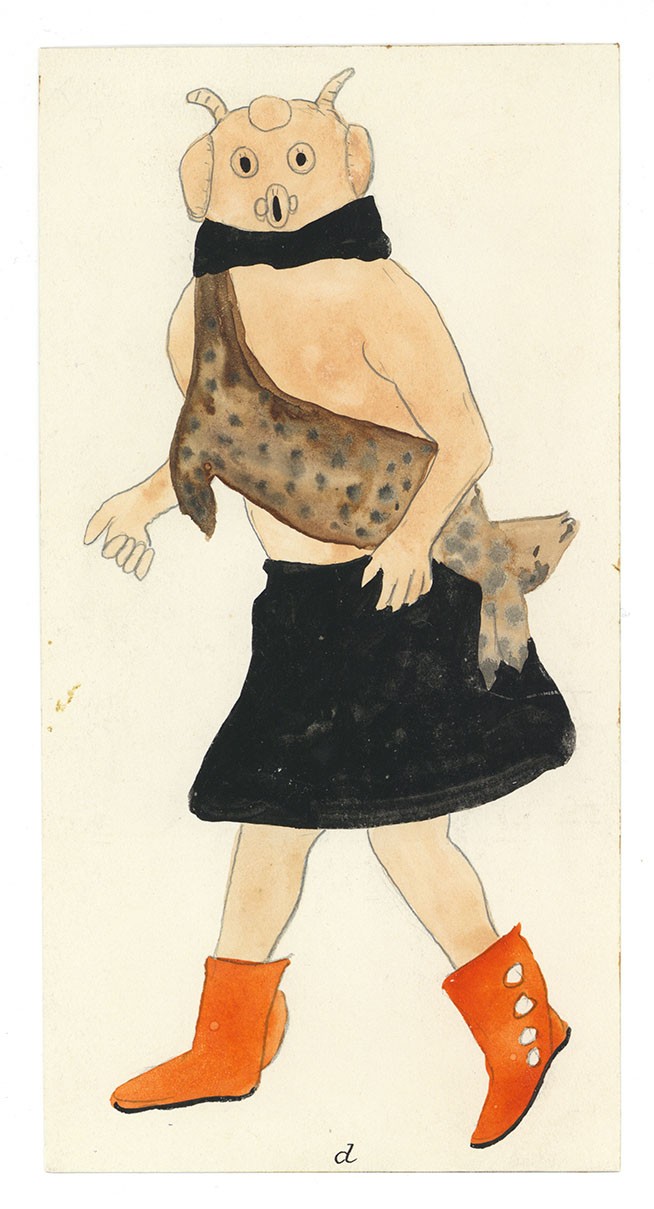

Fig. 5. Unidentified Zuni artist, Kokko painting: Mudhead Clown (Muyapona Koyemsi), ca. 1930, pencil and watercolor on poster board, 7 1/2 x 3 7/8 in. (19.1 x 9.9 cm), Art Properties, Avery Library, Columbia University, The Bush Collection of Religion and Culture (C00.1483.186).

Fig. 5. Unidentified Zuni artist, Kokko painting: Mudhead Clown (Muyapona Koyemsi), ca. 1930, pencil and watercolor on poster board, 7 1/2 x 3 7/8 in. (19.1 x 9.9 cm), Art Properties, Avery Library, Columbia University, The Bush Collection of Religion and Culture (C00.1483.186).

The story of the Kokko is similar to that of the Hopi Katsinam. The Kokko are described as masked representations of benevolent spirit beings who rain blessings upon the Zuni people. However, their representations and purposes are unique to the Zuni tribe and individual Kokko vary greatly from their Hopi counterparts. Even their myths are different. Zuni native Edmund J. Ladd describes the cosmological purpose of the Kokko as follows:

Before the earth became hard, spirits [K/apinna:hoi] from Kolhuwalaaw’a (spirit village), which is our sacred place, came to Zuni in human form, much like the ancient Greek gods. The gods became humans when they came into this world. They performed the Kokko dances, and the women of our tribe fell in love with the dancers and followed them to Kolhuwalaaw’a. But because they were not dead, they could not enter Kolhuwalaaw’a, and it became a great problem. It became such a problem that there were women sitting around the great lake. They couldn;t come home, and they couldn’t go in because their time on earth had not been concluded yet. And so the wise people of our village, the elders, said to the K/apinna:hoi, you must leave your image with us but disappear forever, never coming again to the village in human form, and that's where the Kokko (mask) began in ancient times. (Schaafsma 18)

As with the Hopi, the Zuni masked being holds great spiritual significance. Therefore, its depiction and dissemination is equally contentious.

The Art Properties collection of Zuni Kokko watercolors presumably were displayed and utilized for teaching purposes by Bunzel, and possibly Bush, educating students in Pueblo spiritual belief systems. The mudhead clown Kokkos (fig. 5; Plate 23d in Bunzel) are perhaps the easiest to identify due to their round masks with wide "O" mouths. A smaller doll-sized version of a mudhead can be identified in the back carrying case of another Kokko (fig. 6). According to the Brooklyn Museum, mudhead Kokkos "were created when the Zuni first entered the world. One brother and sister had improper relations so their ten children became Mudheads" [note 4]. There are approximately ten variant Kokkos who perform as mudhead clowns during Zuni ceremonies.

Fig. 6. Unidentified Zuni artist, Kokko painting: Wolatana, ca. 1930, pencil, ink, and watercolor on poster board, 10 x 5 3/4 in. (25.5 x 14.6 cm), Art Properties, Avery Library, Columbia University, The Bush Collection of Religion and Culture (C00.1483.239).

Fig. 6. Unidentified Zuni artist, Kokko painting: Wolatana, ca. 1930, pencil, ink, and watercolor on poster board, 10 x 5 3/4 in. (25.5 x 14.6 cm), Art Properties, Avery Library, Columbia University, The Bush Collection of Religion and Culture (C00.1483.239).

Bunzel's work on these Zuni watercolors is emblematic of a larger practice that took place within numerous Native American communities at the turn of the twentieth century. For instance, in 1903 the Smithsonian Bureau of American Ethnology hired Jesse Walter Fewkes (1850-1930) to catalog drawings of Katsinam in various Pueblo communities for their annual report. These typologies, collectively known as the "Codex Hopiensis," were disseminated across America. The alphabetical labels on the Art Properties collection of watercolors corresponds to how they were published as groups of plates in Bunzel's text, and this labeling mirrors that found in the Codex Hopiensis. While informing the rest of the world about the Katsina cult and attempting to preserve their iconography, taxonomies such as these were also deeply embedded in the exploitation and "othering" of Indigenous cultures and spirituality. Historian Sascha T. Scott explains how the Codex Hopiensis was harmful for native communities:

Ethnographic research was understood by Pueblo communities as invasive and threatening. … As Hopi people learned of the images of Katsinam being created for Fewkes, they asked Fewkes to see them. At first, he shared the images freely hoping to gather more information about Katsinam, but as news about the images spread, their makers became the subject of speculation about sorcery and gossip (a powerful mode of social control among Puebloan peoples). Many Hopi saw the images and their makers as a threat, and these concerns hampered work on the project, according to Fewkes. Fewkes blithely dismissed the fears as the result of some Hopis’ lack of intelligence, and he was able to convince a few of the artists to continue representing Katsinam, knowing it jeopardized their safety. (Scott 6)

Before Fewkes, the only two-dimensional images of katsinam were found in kivas, sacred subterranean chambers decorated with murals. According to W. Jackson Rushing III, "the modernism of these late nineteenth century Hopi drawings resides in the fact that they were not produced for religious use by an internal audience but were made for sale to an external audience. Participation in a cash economy was surely a motivating factor, but just as compelling, I expect, was the desire to communicate pride in the Hopi belief system" (Lynes & Kastner 21). This ignited a patronage system for Pueblo painting, encouraged by the likes of Profs. Bunzel and possibly Bush, as well as non-native modern artists living in and around Santa Fe, such as Georgia O’Keeffe, who painted images of kachinas as well.

Because of this complicated history and the sensitive nature of these two-dimensional representatives, there are some Zuni watercolor paintings in the Art Properties collection that have not been reproduced today, although they have been in the past. For example, accession number C00.1483.198 depicts a Kokko in a Ca’lako house, which was reproduced as a black-and-white image in Bunzel's text. The room in this image is sacred, only to be entered by a priest and those who belong to the Ca’alko winter ceremony. The Ca’lako are giants identified by their height and a long snout. The figure in the center of this watercolor wears a Ca’lako mask which, according to Bunzel, is "dangerous," only to be touched by the priest and the Ca’lako w’ole (Bunzel 969). What happens inside the Ca’lako house is knowledge reserved for only a select few and the image may have been obtained for anthropological and artistic reasons that would be seen as unethical today. This is why consultations with Native American tribes is essential, and why the necessary work in fulfilment of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) can only enhance awareness and respect for Indigenous objects and their origins.

The research discussed in this report on the Art Properties collection of Hopi kachina tihu and Zuni kokko watercolors is just the beginning. The goal of this paper was to provide a brief history and overview of the collection, with the hope that other students, professors, and researchers may learn from these objects and the issues around them, work that has been overlooked for far too long. Identifying, researching, and displaying Native American objects necessitates further action on many levels. This paper is merely one way of demonstrating that need for ongoing dialogue, in this instance with the Hopi and Zuni peoples.

NOTES

1. My thanks to Nancy Rosoff, Andrew W. Mellon Senior Curator, Arts of the Americas, Brooklyn Museum, for her help in clarifying the current use of these terms. Based on recent conversations with Hopi tribal members, the term "Katsina" can only be used to describe the spirit itself and the term is therefore not appropriate for a museum context. Some historians have argued for the use of "katsina" rather than "kachina," which has been seen as the anglicized version of the Indigenous word. Art Properties has attempted to conform to current use by cataloging these figures as "kachina" or "kachina tihu," which also falls in line with established vocabulary practices in the Getty Art and Architecture Thesaurus, although this usage may evolve and change over time.

2. Boy Scout kachina carving kits are still available on eBay and other auctions sites. See, for example, https://www.worthpoint.com/worthopedia/vintage-boy-scout-wood-carving-kit-kachina (viewed May 10, 2023).

3. See, for instance, the Katsina (Shalako Mana) figure in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/310490 (viewed May 10, 2023).

4. See, for instance, "Kachina Doll (Muya Pona [Clown])," in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum, https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/16415 (viewed May 10, 2023).

WORKS CITED

Bunzel, Ruth Leah. Zuñi Katcinas: An Analytical Study. Forty-seventh Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1929-1930 (1932). Reprint. Glorieta, NM: Rio Grande Press, 1984. E99.Z9 B86 1984

Fewkes, Jesse Walter, and Smithsonian Institution. Twenty-first Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution 1899-1900. H.Doc.483. Washington, DC: United States Congress, 1903. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/coo.31924028762361 (viewed May 10, 2023).

Hunt, W. Ben. Kachina Dolls. Milwaukee Public Museum Popular Science Handbook Series No. 7. Milwaukee, WI: 1957. Repub. online, Project Gutenberg, 2020. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/62286/pg62286-images.html (viewed April 12, 2023).

Lynes, Barbara Buhler, and Carolyn Kastner, eds. Georgia O'Keeffe in New Mexico: Architecture, Katsinam, and the Land. Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press; Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, 2012. N6537.O39 A4 2012

Schaafsma, Polly, ed. Kachinas in the Pueblo World. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1994. N6502 P96 K11

Scott, Sascha T. "Ana-Ethnographic Representation: Early Modern Pueblo Painters, Scientific Colonialism, and Tactics of Refusal." Arts 9, no. 1 (2020), available online: https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9010006 (viewed May 10, 2023).

Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives. "Guide to the Ruth Leah Bunzel Papers, 1921-1979," Series 8: Artwork. Available online: https://sova.si.edu/details/NAA.2006-22?t=W&q=watercolors#ref474 (viewed May 10, 2023).