Frommel Essay

SABINE FROMMEL, Director of Studies History of Renaissance Art, École Pratizue des Hautes Études, PSL (Research University Paris), “jo intendo di accompagnare la commodità francese al costume e ornamento italiano”: The Sixth Book in the Avery Library and Serlio’s late stylistic development

When Serlio published the first volume of his treatise in 1537, the Fourth Book on the five orders, he exposed a complete plan of seven books, which contained the Sixth Book on domestic typologies according to social hierarchy.1 The project of this ambitious treatise rose probably during his sojourn in Rome in 1523/25, when he studied antique and modern architecture along with his mentor, Baldassarre Peruzzi.2 Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Baldassarre’s master, had already developed speculations about dwellings appropriate for various social ranks, but it is not certain whether Peruzzi wanted to expand upon such a subject theoretically.3 In any case, after Peruzzi’s death in 1536, Serlio rushed to elaborate his treatise and used materials that he had collected during his time spent in Rome. Before leaving Venice for Fontainebleau in 1541, he also published the Third Book on Roman antiquity, which he dedicated to Francis I, king of France. When he arrived at the court of Fontainebleau at the end of summer or at the beginning of fall 1541, he hoped that the king would finance the publication of his other manuscripts. In 1545 the First and the Second Book were published in Paris by Jean Barbé, followed in 1547 by the Fifth Book on churches, edited by Michel de Vascosan and dedicated to Marguerite de Navarre, the sister of the king.4 In the same year the first French translation of Vitruvius by Jean Martin, illustrated by Jean Goujon, intensified attention on classical syntax and heightened interest in the Sixth Book whose development was quite complex and dependent upon by more personal considerations.5

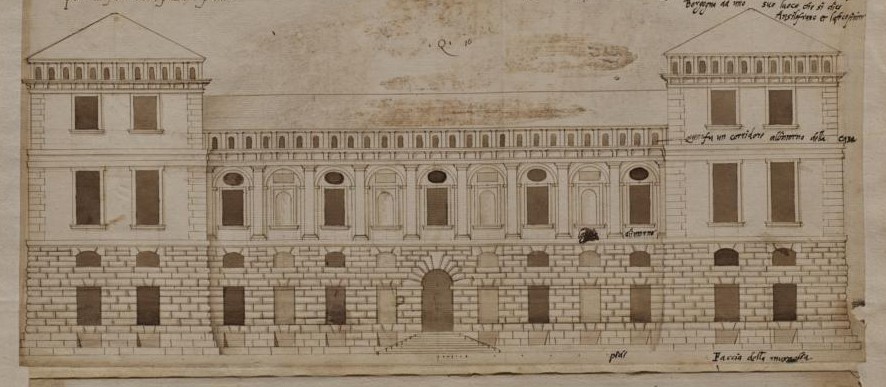

When Serlio arrived in Fontainebleau as paintre et architecteur du Roy, the material that he had collected for the Sixth Book was far from complete and still rather incoherent. The treatise consists in two parts, one dealing with country houses, the other with dwellings in the urban context. Many ground plans reveal an authentic Italian flavour: the variations of the Odeon Cornaro in Padua, two Venetian palaces, a group of fortresses, some large residences with one or even two big courtyards.6 Nearly all the façades of the dwellings of the higher social ranks are however of a hybrid character and incorporate local influence. In France new experiences had in fact provoked immediately a change in the orientation and contents of this treatise. Serlio, who was not really skilled in architectural practice, had received a commission for the Grand Ferrare, the palace of cardinal Ippolito d’Este in Fontainebleau, and the castle of Ancy-le-Franc in Burgundy for an ambitious French nobleman, Antoine III de Clermont-Tallard. (fig. 1, 2a, 2b)7 Furthermore Serlio designed an ambitious project for the reconstruction of the Louvre and proposed to the king a bath pavilion for the garden of the castle at Fontainebleau. Sebastiano was very fond of these projects and if he didn’t insert those of the salle de bal in the cour ovale (1545-46) into the manuscript for Book VI, he did later incorporate them into the Seventh Book, it’s because the sheets had probably been finished before, suggesting that he had put them together in nearly five years.8

These works signified a challenge for Serlio, who had to combine French traditions with the heritage of the High Renaissance without any practical or theoretical background. Exactly such a synthesis became now the leitmotiv of the Sixth Book and provided it with an innovative character: perché nel mio procedere jo intendo di accompagnare la commodità francese al costume e ornamento italiano.9 Serlio had discovered that the local French tradition differed greatly from the Italian one, beginning with the plan’s distribution and now tried to assimilate those local specificities and to reconcile them with classical orders. For the first time Italian dwellings, characterized by a centralized distribution and porticoes with pediments, are compared with French ones, marked by a longitudinal shape and high steep roofs.10 On the one hand the feature of the humble houses of local character obeys Renaissance principles, while the Venetian villa of the Quattrocento, like the villa of Porto Colleoni or Ca’ Brusa at Lovolo, exerts a strong influence, particularly for the layout. As the rank of the habitants increased in nobility, -- for the casa del gentilhuomo per la villa and La casa del gentilhuomo nobile e di buon grado…sopra la piazza -- Serlio no longer differentiates between Italian and French types, attesting that such dwellings depend more upon the free choice of the patron.

The later version of the book, drawn on parchment and held in the Staatsbibliothek in Munich, and the printer’s proofs of woodcuts in the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek of Vienna, carved in France in the 17thcentury, reveal Serlio’s typological and stylistic evolution during his French period.11 The existence of three different versions of nearly all the drawings, drafted in a relatively short period of time, is a rare opportunity to observe the progressive changes of his idioms and methods.

Serlio’s experiences as an architect: practice and theory

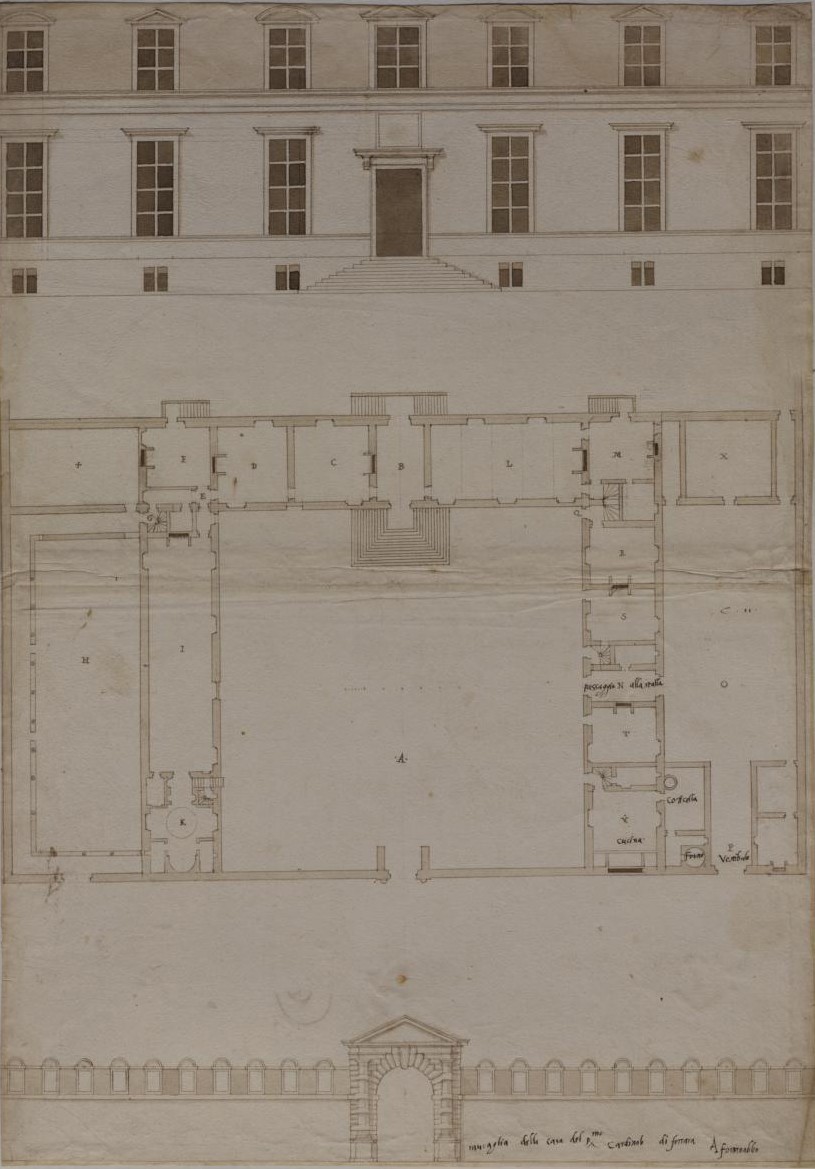

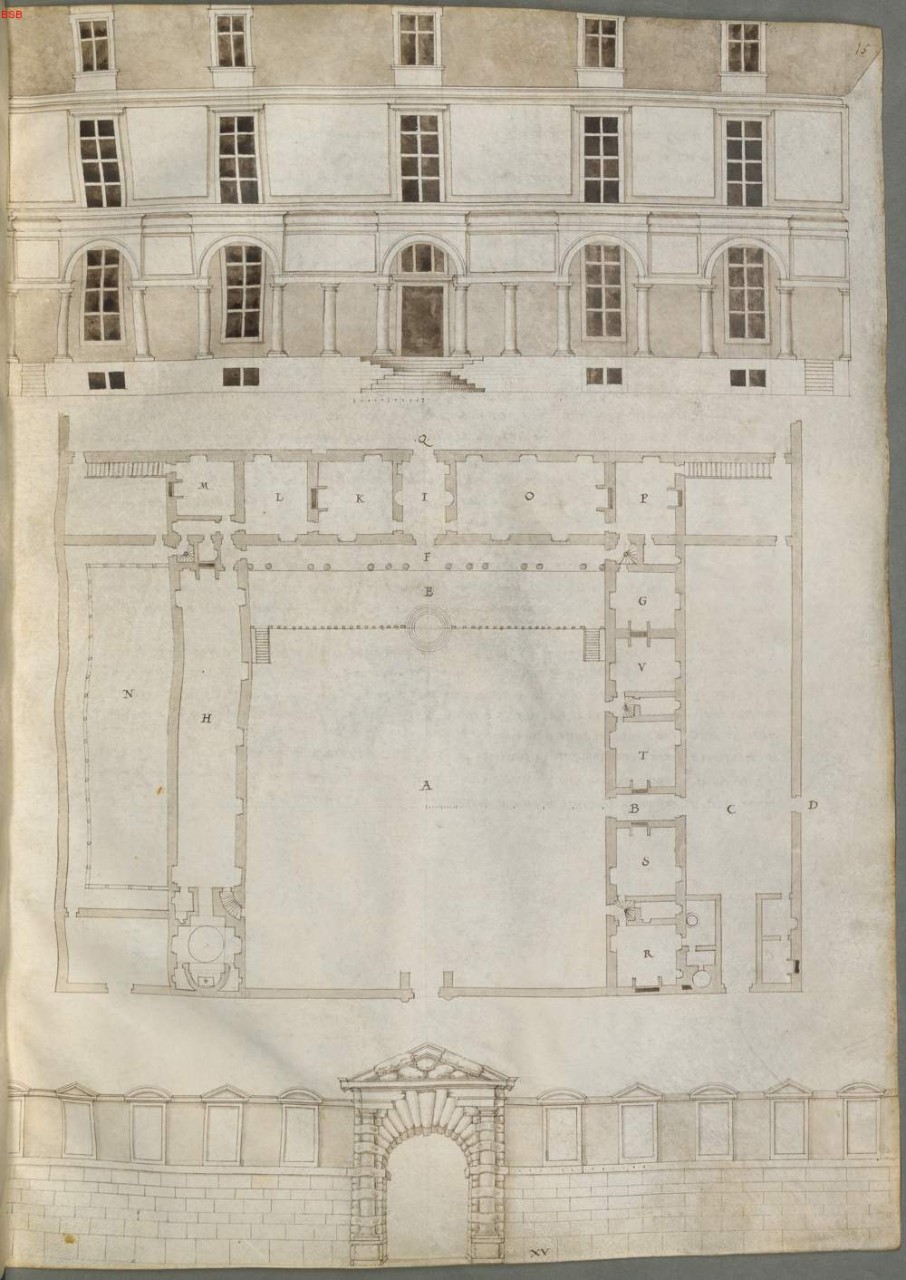

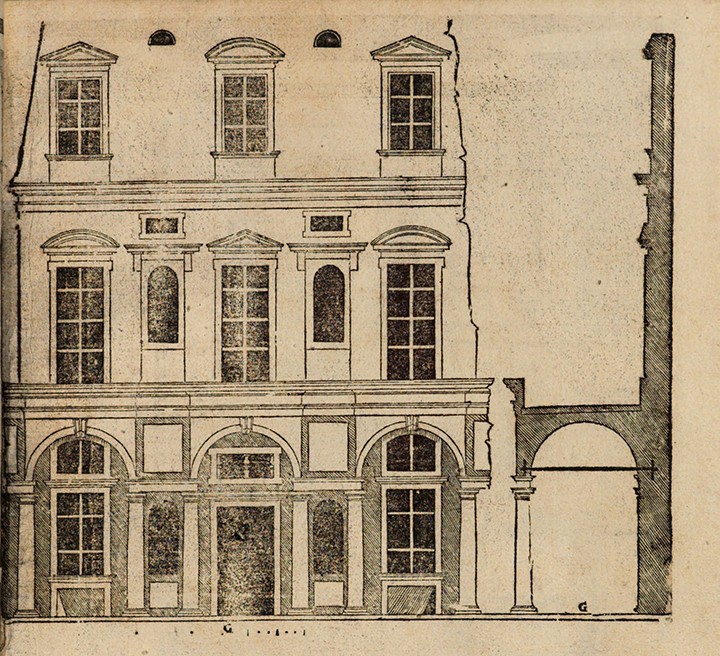

For diplomatic reasons, the cardinal d’Este restrained his architectural ambition so that his palace would not compete with the castle of the king, situated in front of it. In the main wing Serlio combined a central vestibule and an Italianate anticamera with the typical French gallery, linked to the chapel, that occupies the left wing (fig. 1).12 The building is made of irregular stones with plastering, the walls feature windows crowned by elegant cornices, with no architectural order. The openings’ slender proportions and the heavy dormers are specific French features.

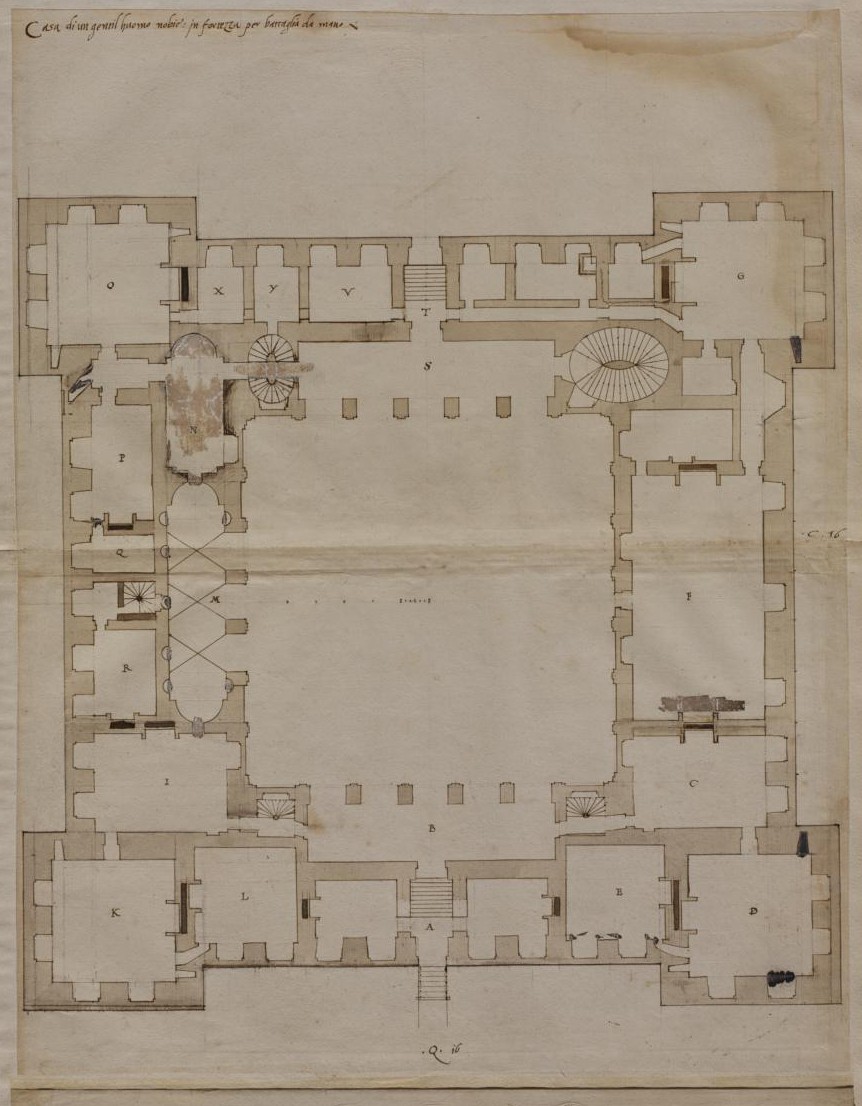

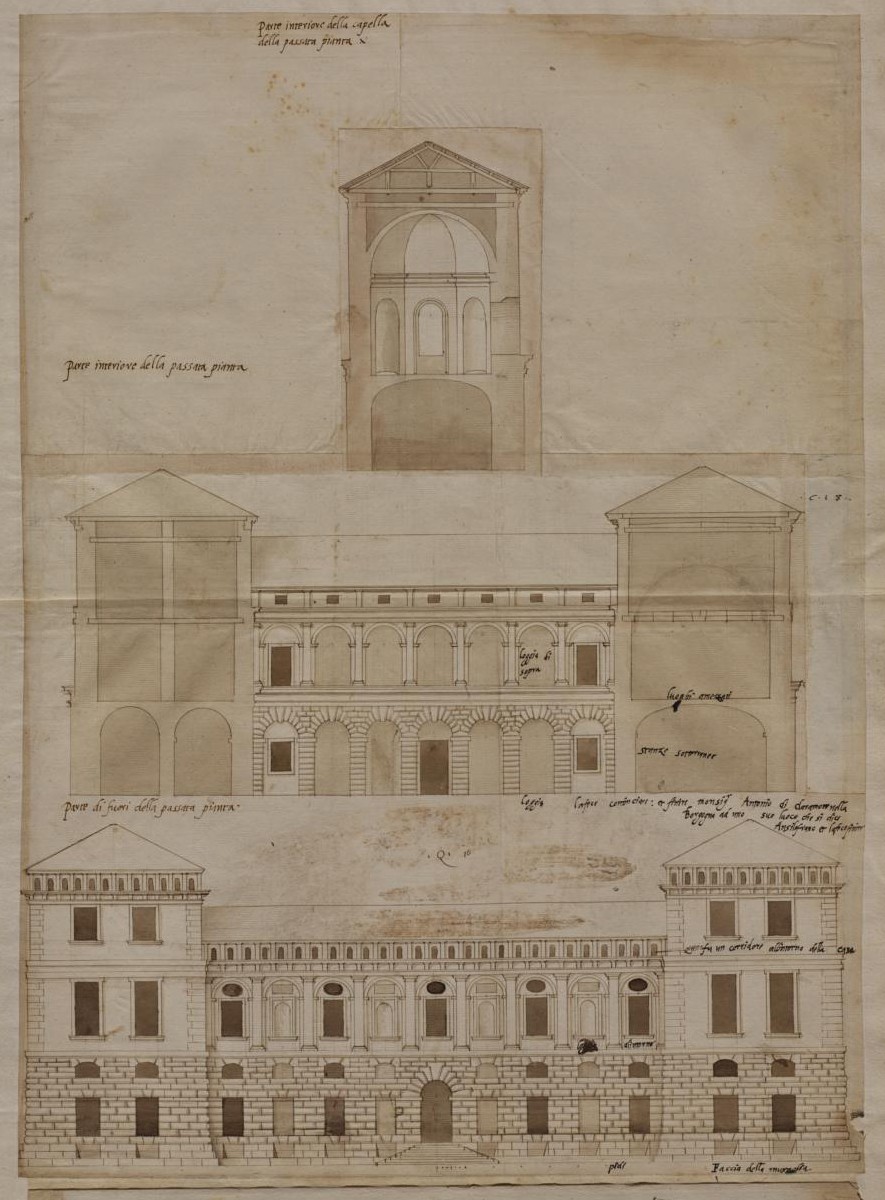

Through a rusticated doorway, the only element visible today, one enters the courtyard. This gate proved so successful that Serlio eventually dedicated a whole book to doorways, the Libro extraordinario (Lyon, 1551).13 The cardinal hesitated for a long time when his brother Ercole asked to see a survey drawing of the building and pointed out that its quality is due to the fact that it is appropriate for the place and for the function Quanto al disegno….V.Extia. sappi, che ella è assai manco infatti di quel chella ha per avventura il nome, Et quell chella deve far forse nominar per bella, credi che sia piu tosto per esser fatta nel luogo, dove è, et dove par che sia piu di quell che vi convegneria….14 For this reason is not surprising that Ippolito forbid Serlio to publish the drawings.15 The case of Ancy-le-Franc was very different, because the nobleman from Dauphiné, who had unexpectedly inherited a large sum of money, wanted to build an Italianate castle. He was well-informed about the increasing influence of Italian art at the French court and commissioned the king’s paintre et architecteur to draw the project and supervise the building site. Serlio’s comments in the two versions of the Sixth Book clarify the rather complicated genesis of the project.16

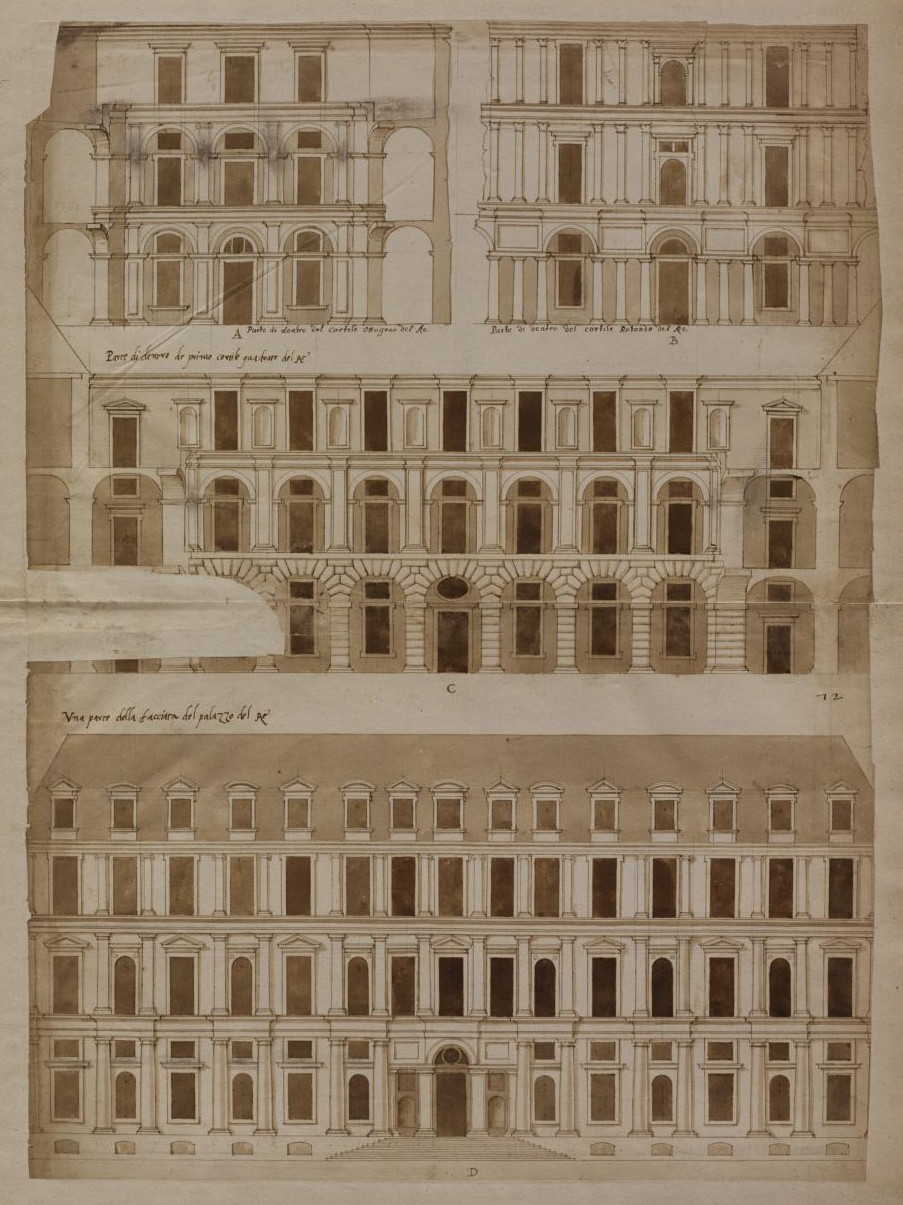

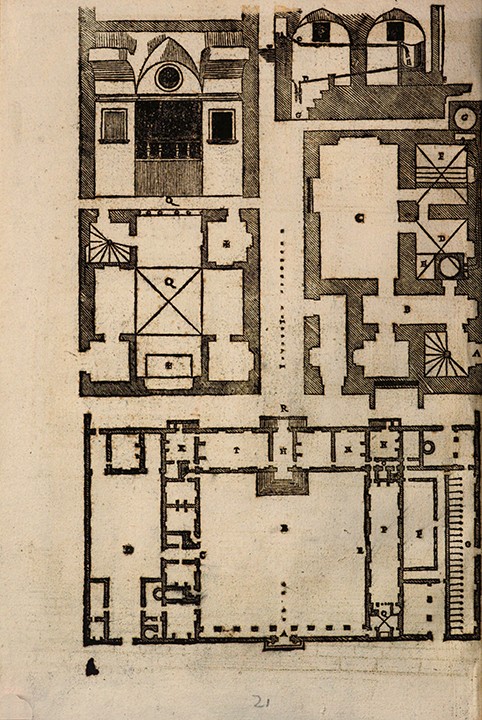

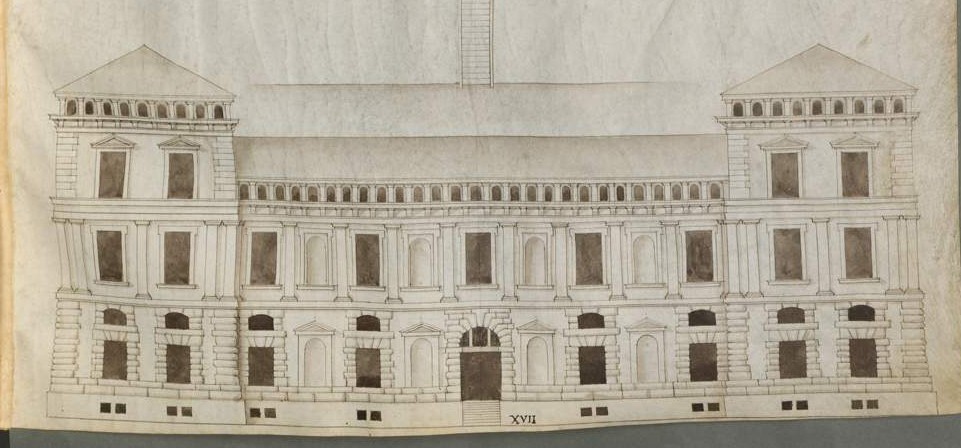

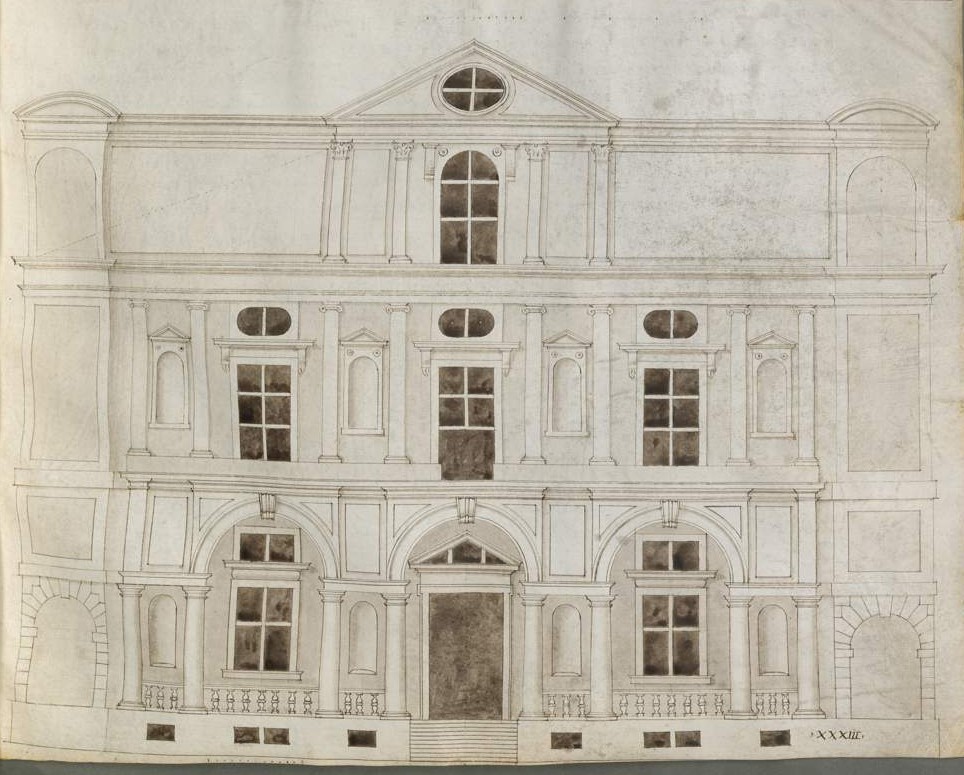

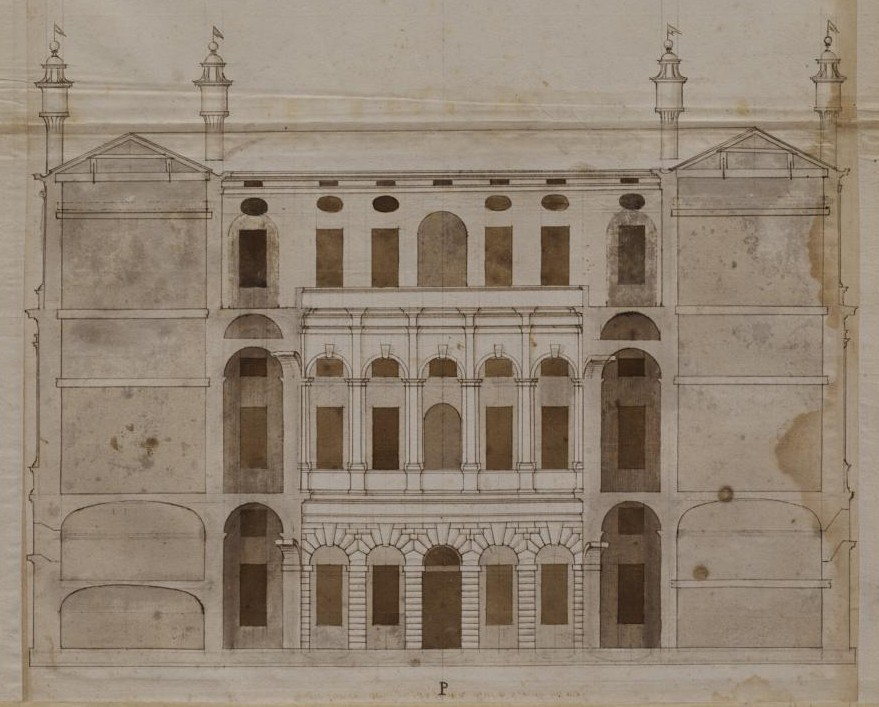

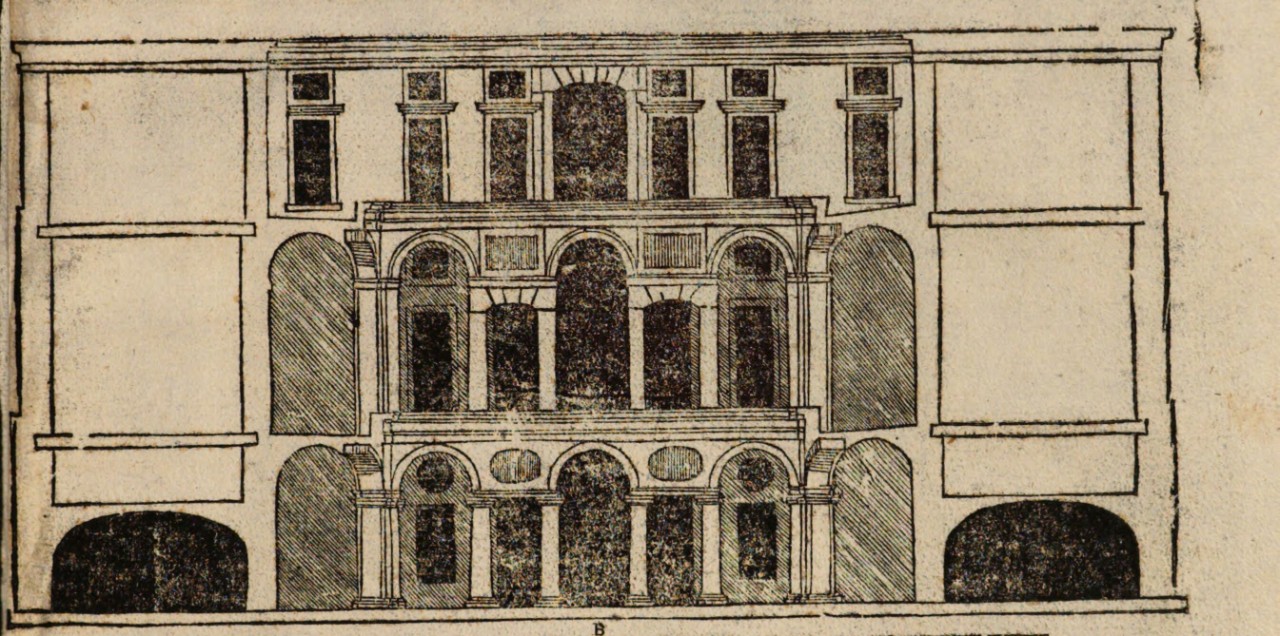

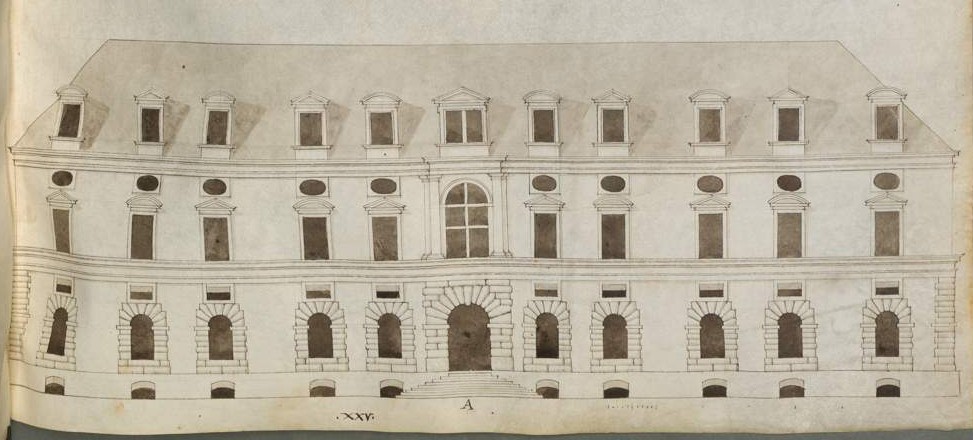

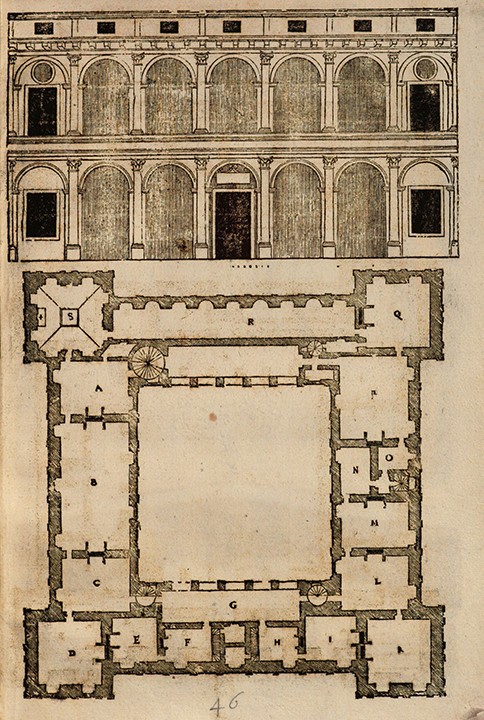

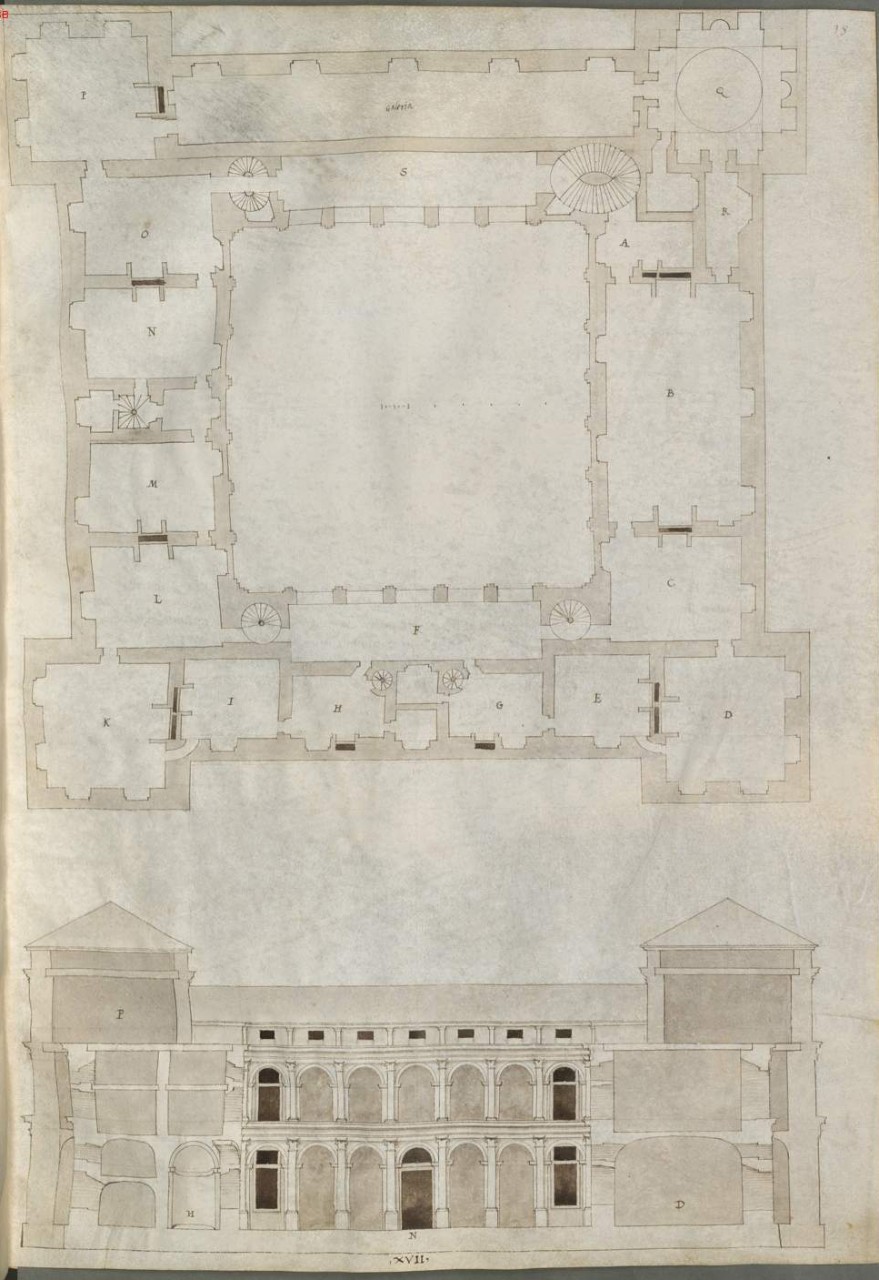

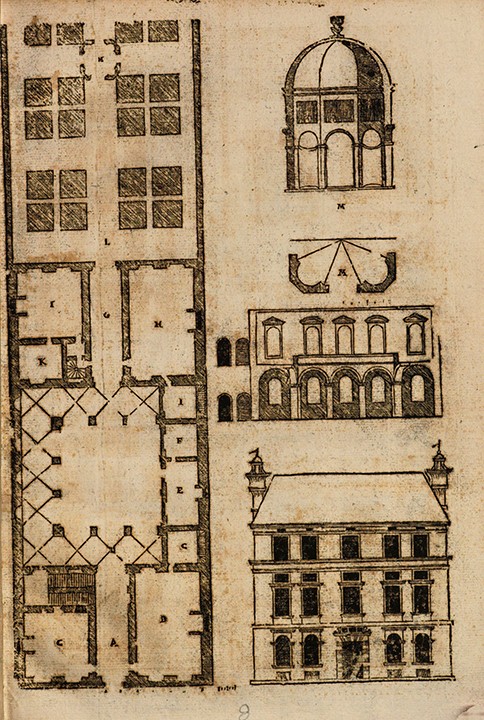

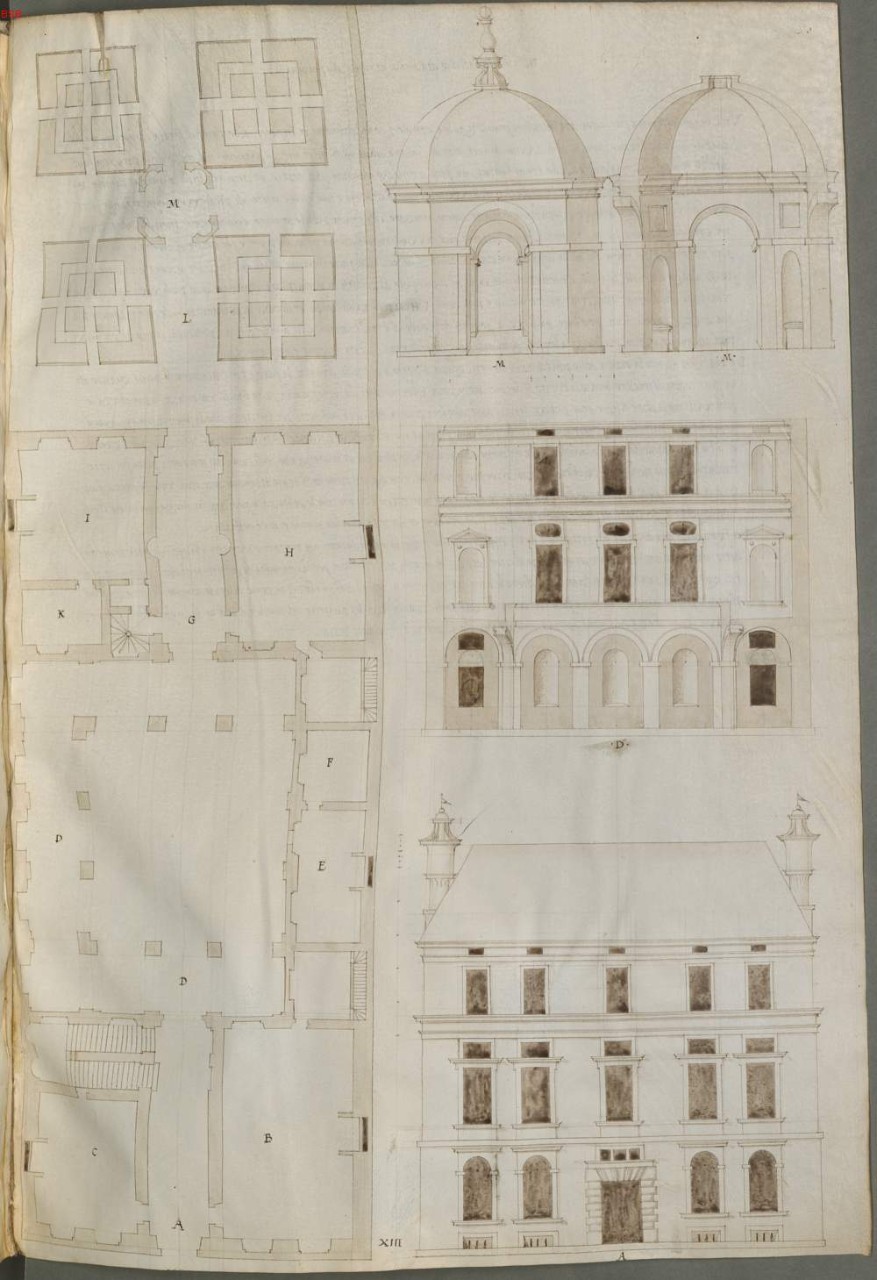

The drawings of Avery Library’s manuscript give a clear idea of Serlio’s attempts to reconcile the two traditions (fig. 2a, 2b). In contrast to the hierarchical differentiation of wings in French dwellings, the four aisles share the dimensions and architectural orders of an Italian palace. All the façades are characterized by the contrast between a rusticated ground floor and a regular succession of arcades, partly closed, providing a homogenous design all around the building that even in Italy had almost no forerunners, with the exception of villa at Poggio Reale in Naples, a building familiar to Serlio.17 In contrast to the Doric pilasters of the first story of the exterior, in the square courtyard the Ionic order recalls Jacopo Sansovino’s Venetian Palazzo Corner and Zecca.18 The French influence is obvious in the absence of a continuous wall surface and the vertical proportions of some windows. According to Italian Renaissance principles the plans had been extrapolated from a geometrical grid and the stairways were hidden in the corners. Nevertheless, on the walls of some of the main rooms, the windows are irregularly positioned, diffusing unequal light and showing how Serlio did not succeed in fitting the rhythm of the façades with those of the courtyard. Apparently it was easier to convince the patron to use Vitruvian orders than to find the right shape for the plan’s distribution. Serlio was forced to introduce a high northern roof, which affected the equilibrium of his classical orders. In varying the project (f.XIX), he declared that the decisions had been strongly influenced by the patron and that he wanted to propose a solution according to his own ideas (fig. 3).19

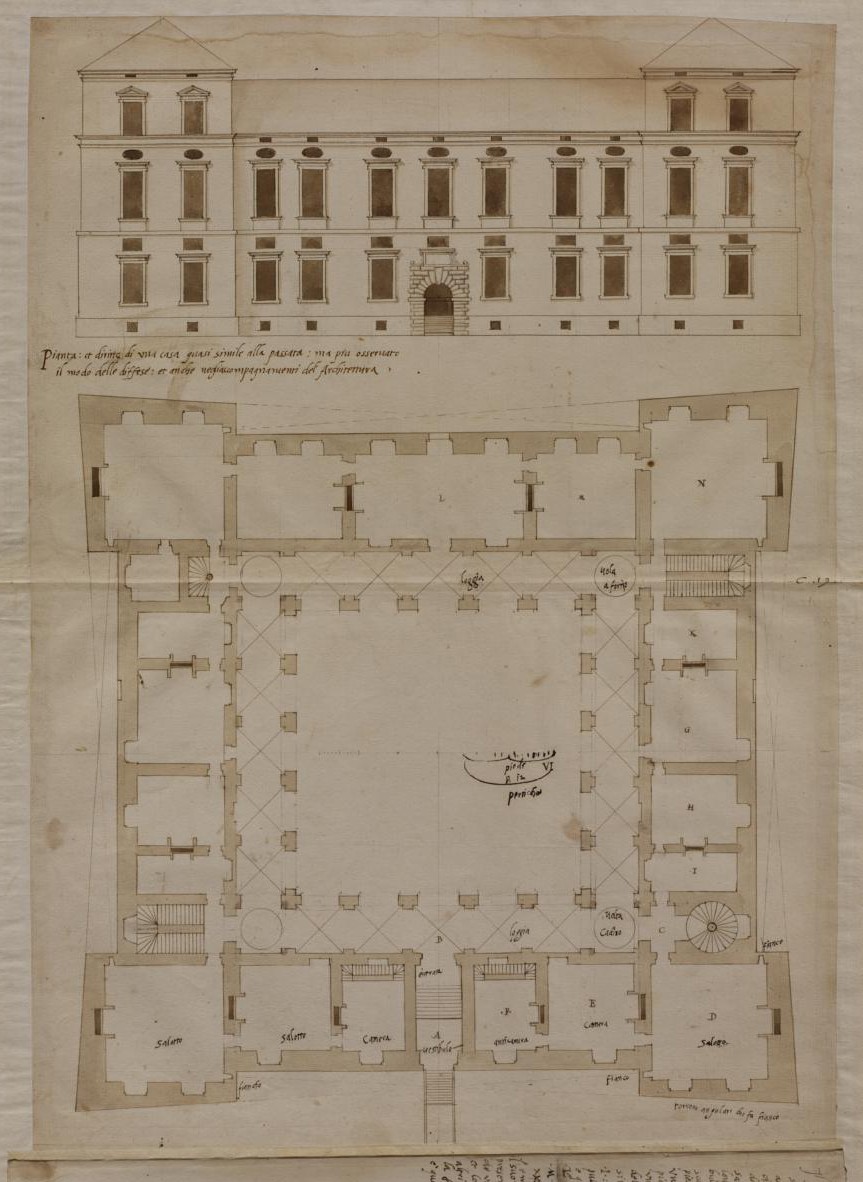

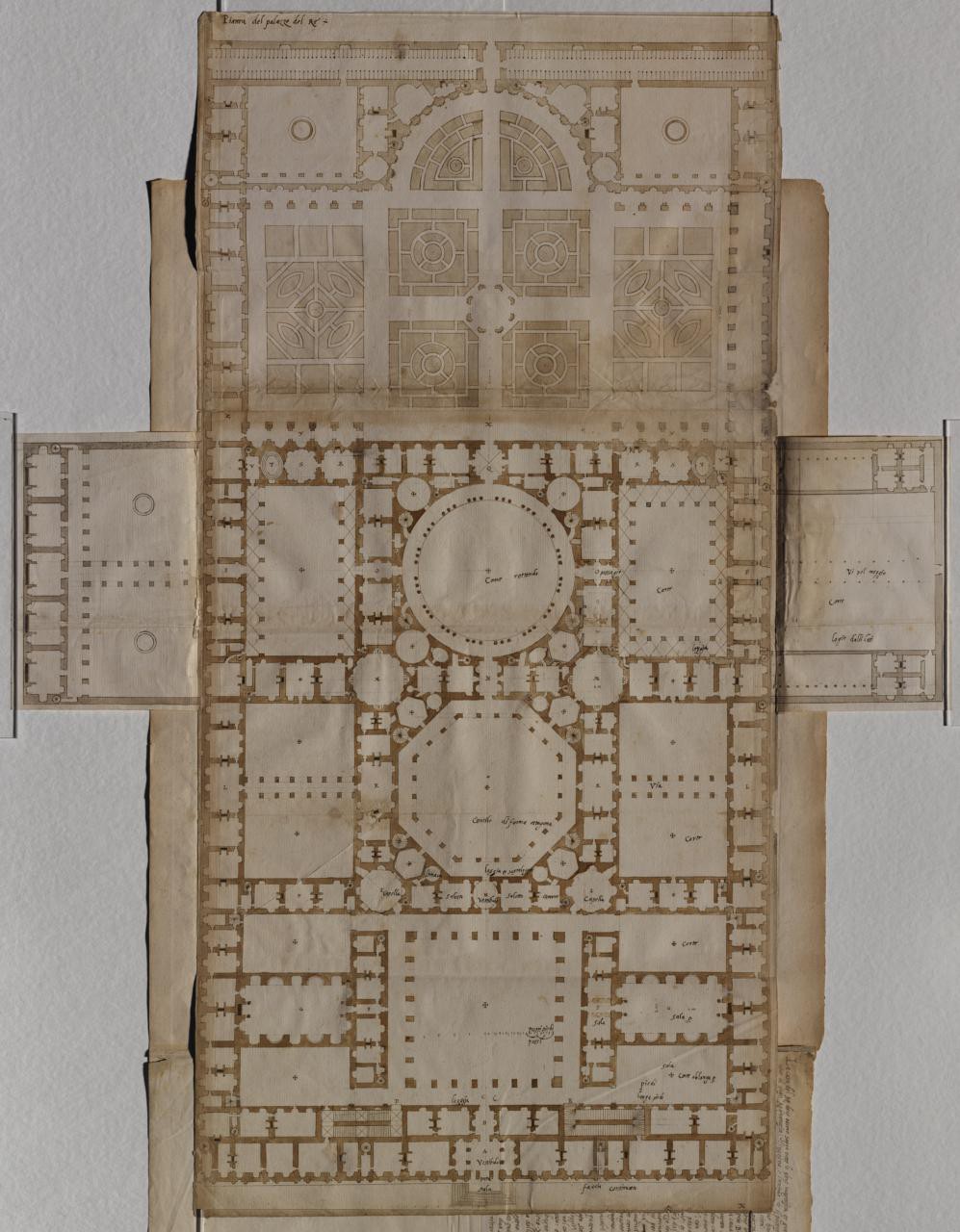

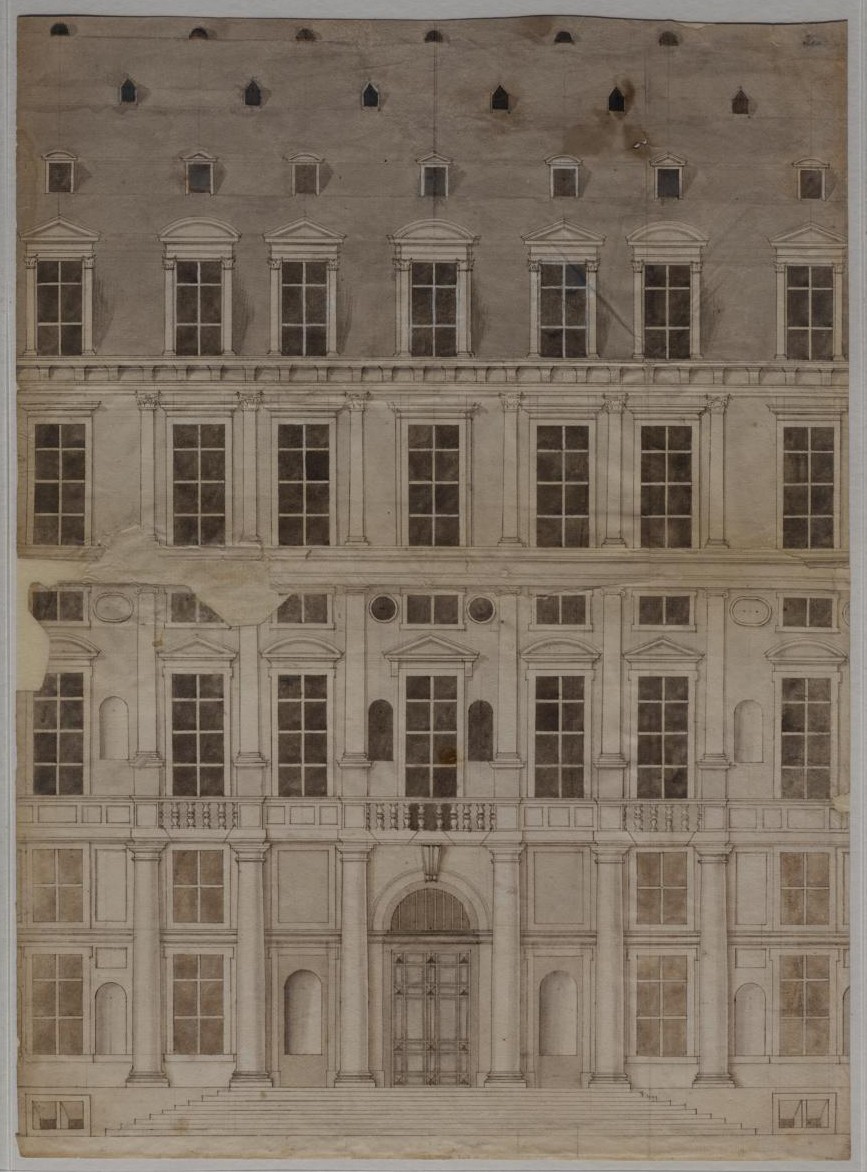

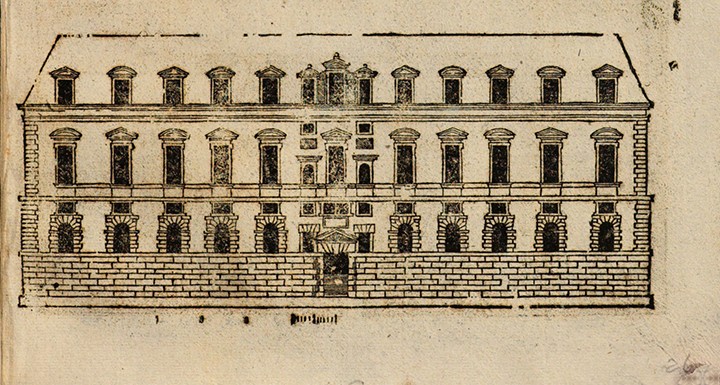

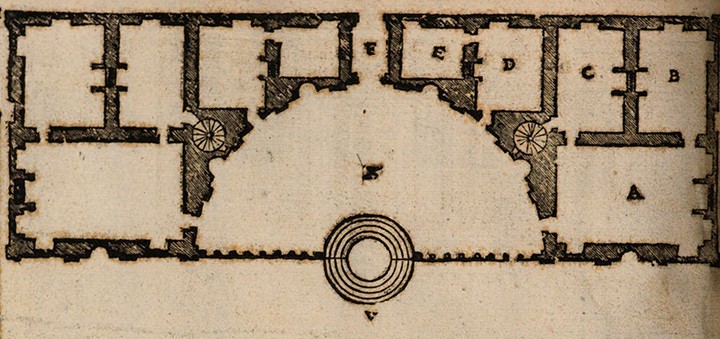

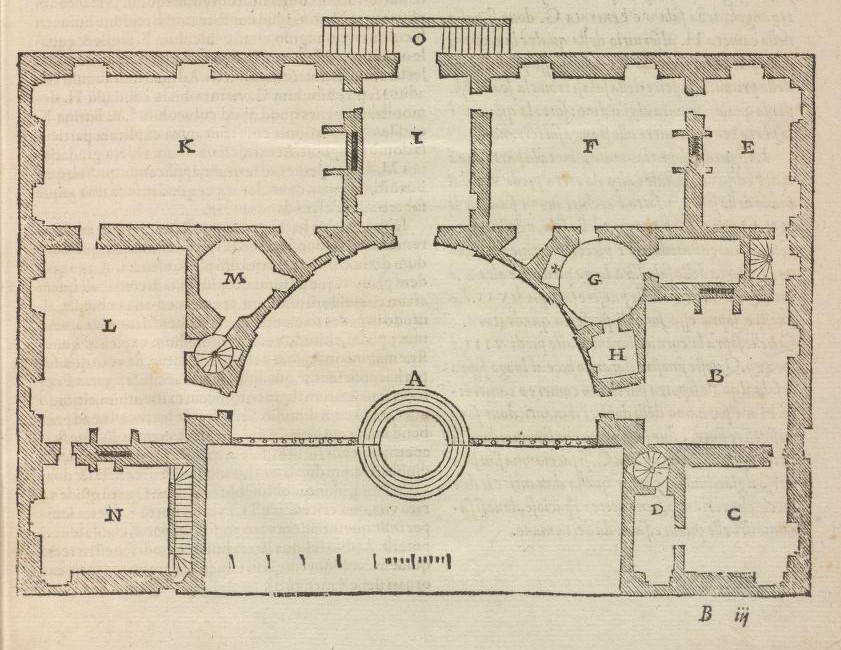

The ambitious project for the reconstruction of the Louvre can be dated a little bit later because of the stronger ascendant movement of the façades, at least in the exterior (fig. 4a, 4b).20 The sequence of circular and octagonal courtyards was inspired by Peruzzi’s project for a monastery (GDSU 350Ar); the octagonal area in the middle with centralized chapels in the corners recalls ideal projects of Francesco di Giorgio and Leonardo da Vinci.21 The square courtyard with its rusticated arcades again brings to mind a Sansovino’s Venetian courtyard but the details are bolder. The most astonishing feature is the circular courtyard, perhaps also related to the palace of Charles V in Granada, with its rhythmic grouping of columns alternating with arches reminiscent of the garden façade of Giulio Romano’s Palazzo del Te.22 Oblong panels are placed between the arches whereas the order is animated by the use of the typical Venetian form of recessed arches with a projecting wall above. The large semi-circular exedra, provided by niches for statues, would have exceeded the scale of the Nicchione of Bramante’s Belvedere court in Rome and would have anticipated the teatri in baroque gardens.

The sequence vestibulum, atrium follows Vitruvian principles and the ceremonial staircases in the corners of the square courtyard recall Roman precedents like Bramante’s 1506 Vatican Scala Regia, or the final solution for Palazzo Farnese’s staircase (begun in 1540). The large three-storeyed audience halls on each side, the centre point of social life, seem to be conceived as a basilica with tribunal (fig. 4a).23 Like in the case of the Grand Ferrare in the back wing a magnificent bathing facility comprising dressing room, sudarium and proper bathing room is connected with the garden.24 Models coming from the High Renaissance are again dominant and the role of Peruzzi and his masters – for example, Francesco di Giorgio -- is more than evident.

From Avery Library manuscript to the Vienna proofs of woodcuts

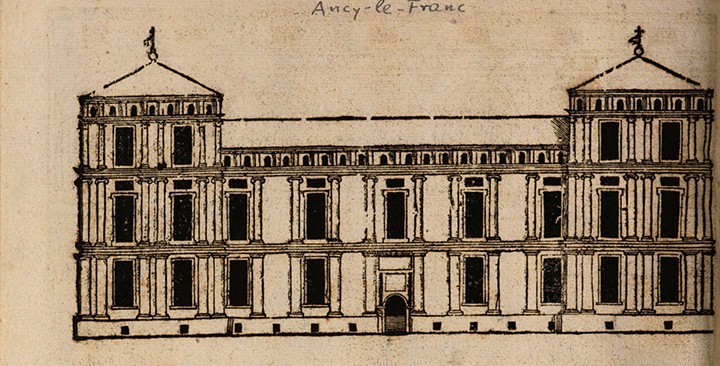

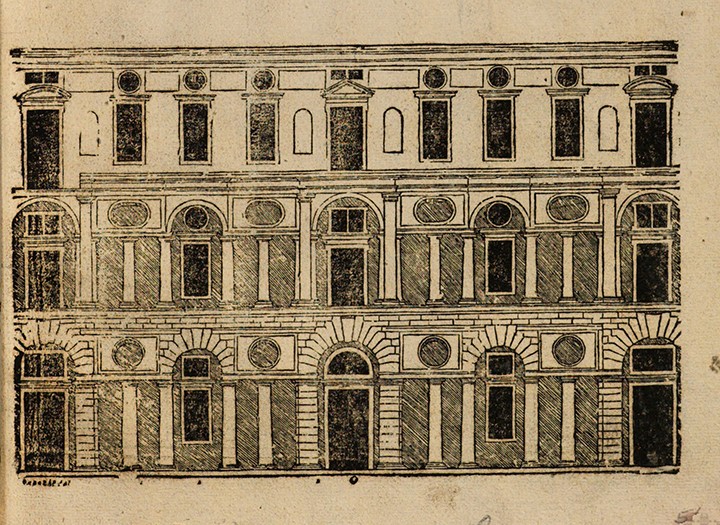

On May 5th, 1546 Giulio Alvarotti informed the duke of Ferrara that Serlio had prepared a collection of drawings and wanted to print them in a few days: lo farà stampar tra pochi giorni.25 This is confirmed by another letter written in October in which the cardinal d’Este let his brother know that he had asked Sebastiano to remove the drawings concerning the Grand Ferrare from this treatise: ha ultimamente fatto e che vuol far stampar.26 It seems that the printer’s proofs of the Vienna woodcuts correspond to this edition.27 In Fall 1546 the preparation of the plates, containing 52 of the 54 projects of the Avery Manuscript, must have been close to a final stage. The fact that some representations of the humble categories of the country houses are inverted in incorrect manner reveals that Serlio had a draftsman work on his behalf.28 The proofs reveal significant stylistic changes. In the case of the Grand Ferrare the presentation is more detailed and contains a section showing the inner spaces including their windows, chimneys and ceilings (fig. 5a, 5b). Also the famous bath in Italianate style, composed of three rooms, is represented, including the technical details. The façade emphasizes the central motif with the triple openings. As far as the castle of Ancy-le-Franc is concerned, the woodcut reflects the debate between Serlio and his patron: the façade’s rusticated basement and the courtyard, as illustrated in the Avery manuscript, had been abandoned and all the stories are articulated by an order of pilasters that underlines the vertical French traditional continuity (fig. 6a, 6b). Nevertheless they don’t represent the project according to the way the castle was built when Alvarotti wrote his letter. This reveals that Serlio’s didn’t aim to document his project, but to remember some step of its evolution.

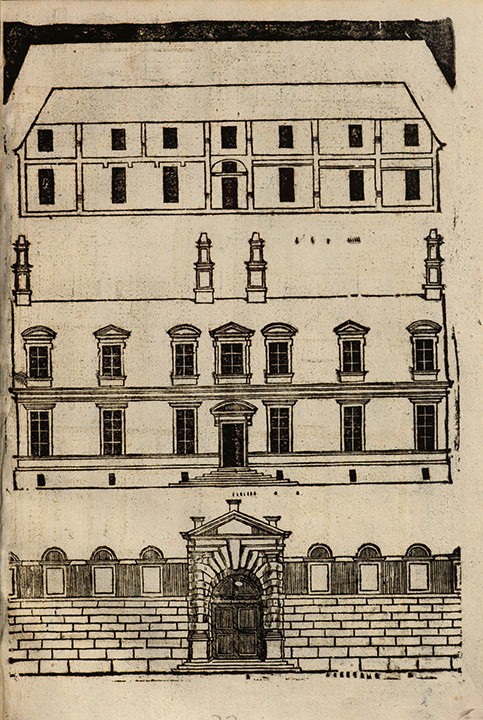

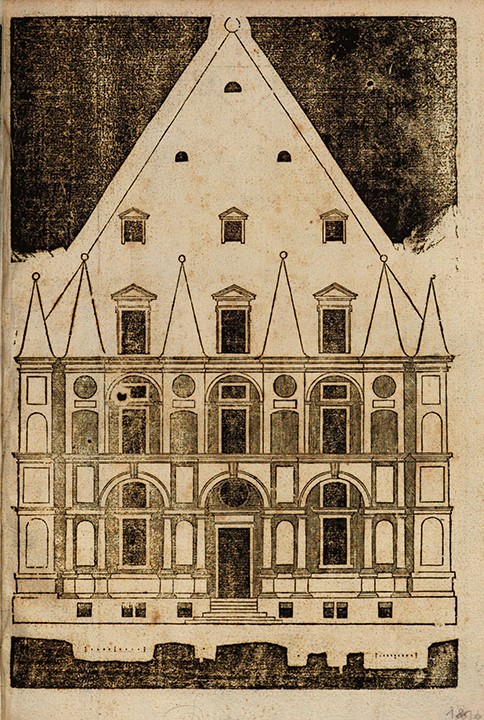

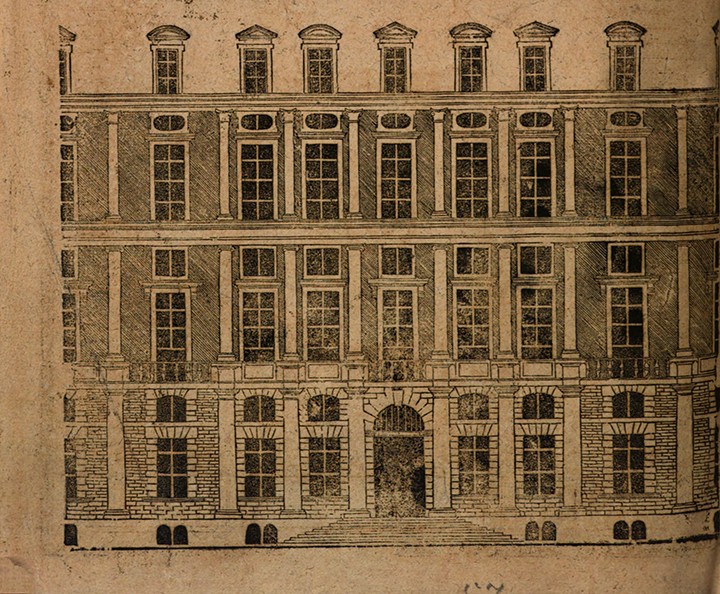

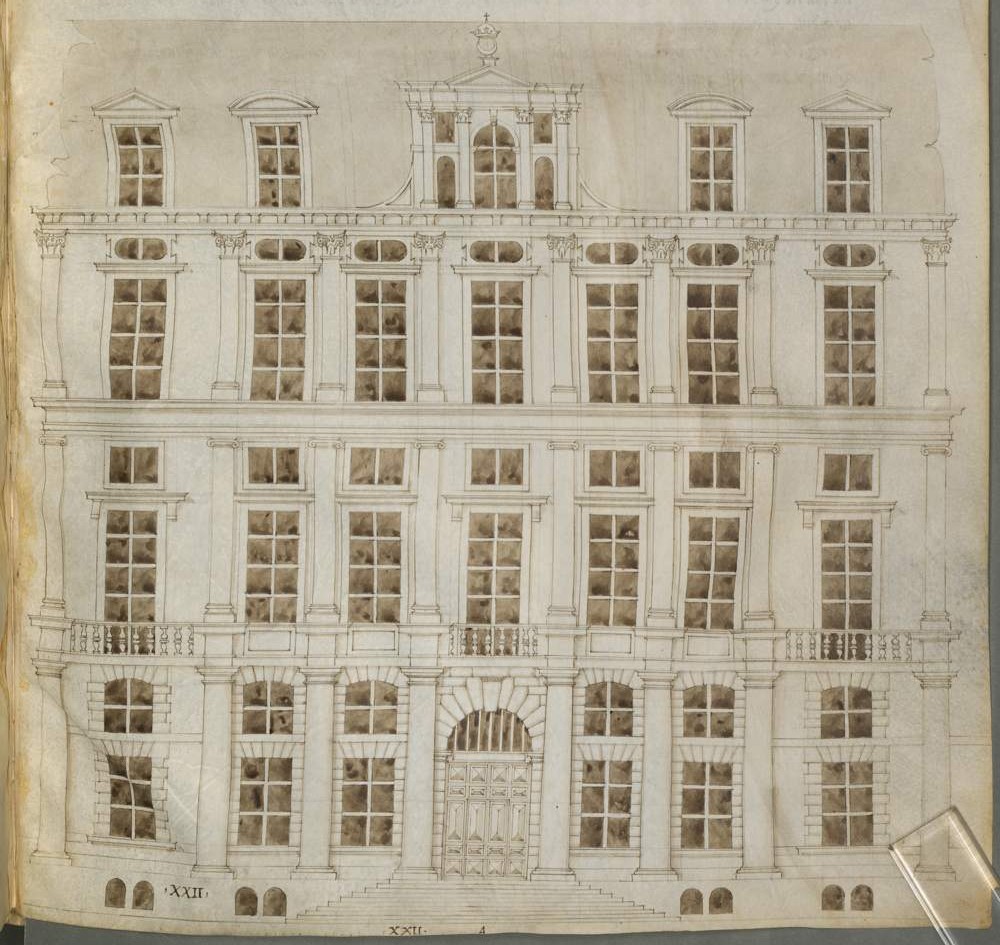

While the ground plans show only slight variations compared to the Avery manuscript, the façades generally boast very different patterns, mark new tendencies and a growing distance from Italian principles. In the case of the piccola habitazione di un principe, a variation of Falconetto’s Odeon Cornaro in Padua (f.XXXVII), the continuous sequence of narrow arches in the first floor is substituted by an alternating rhythm of arcades and smaller bays. The latter ones are crowned by pointed roofs rising on the projection of the entablature, (fig. 7a, 7b). Above is enthroned an enormous northern comble of a pyramidal shape, much higher than in the Avery Manuscript drawing. A new vertical energy and a stronger contrast between the walls and windows differ from Avery manuscript’s drawing and do not make it easy to identify Serlio’s calligraphy. The Louvre façade reveals a similar phenomenon (fig. 8a, 8b): In the three stories all the windows are combined with smaller size openings in order to increase vertical movement. In the same manuscript Serlio framed the portal with two blind bays provided with niches, but the master of the woodcuts opened them with other windows, reducing the monumental character of this triumphal arch. More complex rhythms were privileged in the Vienna draft, where one of the Venetian palaces serliane substitute the paratactic rhythm of arcades, rusticated on the ground floor, and with smooth pillars adorned by pilasters in the first floor, continuing with an ascending momentum up to the entablature (fig. 9a, 9b). Such strong changes, which in some cases totally compromise the Italian flavour of the projects, can hardly be attributed to Serlio.

The Sixth Book of the Münchner Staatsbibliothek

This manuscript was probably started at the beginning of Henry II’s reign c.1547/48.29 To conserve his position and privileges, Serlio had to recommend himself to the new king, who was less interested in architecture and more attentive to local traditions, an attitude that became immediately obvious with the appointment of Philibert Delorme as a surintendant at Fontainebleau. Serlio tried then to direct the projects toward of local taste and patiently redrafted them one by one, providing more monumental features and varying their skin. Such polyphony is emphasized by higher windows that overwhelm the wall, with the result of dissolving the surface, the latter an essential feature of Italian Renaissance architecture. As the buildings of the Grand Ferrare and the castle of Ancy-le-Franc were nearly finished according to their projects, of which Serlio was evidently not satisfied, he felt now free to transform them. He considered the cardinal’s dwelling not suitable to his own rank and enriched it with a portico provided with elegant serliane; delicate panels punctuate the wall, animating it by a subtle play of light and shadow (f.14v, 15r) (fig.10). In the case of Ancy-le-Franc, the Bolognese architect reintroduces patterns from the Avery manuscript: the mezzanine and the walkway under the roof; the rusticated order is now limited to the corners and the windows (f.16v-17r) (fig. 6a, 6b, 6c).

According to Francesco Paolo Fiore and recently to Julian Jachmann, the woodcuts proof of prints refer to the Munich version and would have been executed afterward, as the last draft of the Sixth Book.30 As a matter of fact this would fit with the normal procedure, even more for the parchment version takes in consideration the inverted position of the woodcut, and maintains sufficient space under the commentaries for a text written in Italian. Apparently there is no doubt that Serlio intended to publish the drawings of the Münchner Staatsbibliothek as woodcut prints. As is pointed out above the Vienna woodcuts seem, on the contrary, to precede the parchment manuscript and fit with the publication announced by Alvarotti and the cardinal d’Este in 1546. As no document exist to clarify the chronology, one can really only on stylistic details.

Several façades of the Munich manuscript are improvements of the woodcut version. For example in the villa with an octagonal hall in the centre Casa per la persona di un principe per suo passatempo con pocha famiglia fuori della città, the sequence of bays crowned by singular high roofs is substituted by a clever hierarchical feature: a large motif in the centre is crowned by a upper structured emphasized by triangular pediment. (f.21r) (fig. 7b, 7c).31 It is linked to the external bays by a sort of attic. Serlio got rid of the roof conferring to the building a sacral appearance. It is hardly believable that after having refined the solution, he turned back to the less convincing system of Vienna. The same is true for the main façade of the Louvre, where several dormers had been united in a powerful motif emphasizing the centre, which showed a new way to monumentalize French patterns through Italian methods (fig. 8b, 8c). In the courtyard of a Venetian palace the woodcutter had difficulties to define a harmonious relationship between the stories - the ground floor is too low in relation to the piano nobile - while the parchment drawing is characterized by balanced proportions and accentuates, thanks to projecting arcades, the contrast with the bays. (f.55r) (fig. 9b, 9c).32 That Serlio rectifies flaws of the Vienna version in the Munich manuscripts revealed also in the casa di un gentiluomo where the central openings are flanked by a poorly arranged group of windows and blend-fields, which he arranged in a more convincing manner (f.25r) (fig. 11a, 11b). The Munich drawings often reconnect with the Avery manuscript: the woodcut of the habitazione di un gentiluomo in a pentagonal pattern privileges its sober design instead of arcades combining stone and brick and a piano nobile with alternating high windows and blend-fields (f.XXXI, f.19r).

In other cases, the Munich manuscript completes what had been sketched in the Vienna draft. Serlio accurately reported the sequence of windows that had been added in the section of the Palazzo del Podestà, in the front elevation of the courtyard. As for the circular courtyard of the Louvre, the parchment version adopts the serliane of the first floor as well as the sketched features and the ornaments (f.71r) (fig. 12a, 12b). As far as the circular courtyard of the fortified residence is concerned, only in the Munich manuscript he added the moat and dormer-bridge around the building and strengthened the military equipment (f.XXVII, f.28r).33

The fact that some of the Vienna woodcuts remain true to the Avery manuscript and other ones anticipate the parchment drawings of Munich manuscript shows that some of them had been elaborated in the meantime and new material, like another project for the Louvre, had been added before the carving of the woodcuts had started. In this way can be explained also some improvements of ground plans in the version of Vienna.34 A detail like the crescent, that appears as the emblem of Diane de Poitiers, the favourite of Henri II, as an allusion of the goodness of the hunt, suggest also that the preparation of the woodcuts went on after the death of Francis I.35

The destiny of the Vienna woodcuts

These woodcuts reveal both Serlio’s stylistic evolution as well as the taste of an apparently French artist craftsman who prepared the plates. In contrast with the Seventh Book, which had been drawn on pear tree wood under Sebastiano’s direct supervision, this master seems to have worked with more freedom. Perhaps he had been a woodcutter from Fontainebleau or from the milieu of Jean Martin - Serlio’s books translator - or of Parisian publishers like Jean Barbé or Michel de Vascosan.36 It would be a tempting hypothesis to take into consideration the name of Jacques Androuet Du Cerceau, the owner of the Avery manuscript, who added French titles on nine of the sheets.37 But du Cerceau printed eau-forte on copperplate from 1539, using for the representation of architecture, peculiarities of the woodcut like parallel or diagonal lines.38 However, the Vienna woodcuts neither reveal his technical nor his stylistic peculiarities. The name of the French alleged collaborator must remain unknown.

But why and when were the woodcuts abandoned? The corrections and improvements of the Munich parchments show that Serlio was not satisfied with the plates. This aspect concerns not only the drawings and the wrongly inverted figures at the beginning, but also the layout of the sheets. In all his treatises Sebastiano adopted a rational and balanced relationship between ground plans, façades, sections and details, combining in a skilful manner didactic and aesthetic need. This layout reflects his own architectural principles of regularity and harmony. The woodcuts are far from this level: plans and front elevations are not always symmetrically linked. In some cases the scale changes between representations, like the section of Ancy-le-Franc courtyard. Others are less convincingly recomposed and often details are randomly dispersed (fig. 13a, 13b). This is in itself a reason not to date the woodcuts after the parchment drawing of Munich, because it would signify that Serlio betrayed his own rules at the end of his career! A significant example is the casa del ricco cittadino o mercante dentro la cità, where the woodcut reduces nonsensically the façade of the courtyard to only two stories and adds two isolated arcades at the left side (50r) (fig. 14a, 14b). Above he included a detail of the ground floor and the section of the garden pavilion. As this detail doesn’t exist in Avery manuscript, Serlio seems to have used figures from the Fifth Book.39 The parchment sheet shows how skilfully he reorganized the layout of the sheet, juxtaposing the façade on the top as well as the section of the pavilion which is drawn differently. It happened even that he mixed up the prototypes as in the case of a ground floor of a semi-circular villa, published later in the Seventh Book (fig. 15a, 15b).40

Another reason which could have led Serlio to renounce to the publication concerns the technical quality of the woodcuts. In the Seventh Book he successfully accomplishes to distinguish foregrounds and backgrounds by vertical, horizontal and diagonal hatching. The woodcutter works neither with the same care nor with a systematic method. A comparison between the façade of the circular courtyard of the casa di un principe serrata in un loco forte per battaglia di mano fuori della città (f.XXIX) and the Sesta Proposizione (p.108) reveals the difference of quality (fig. 16a, 16b). So it seems clear that Serlio could not approve the publications of prints whose quality did not correspond to his standard. At the same time, he was aware that du Cerceau’s technique on copperplate was much more sophisticated and he would therefore use it for the Extraordinario libro, published in 1551.41 The prohibition of the cardinal d’Este against the inclusion of the Grand Ferrare forced him to renounce on one of his own projects. Last but not least the death of Francis I in April 1547 had weakened his position within the court and compromised the outcome of the project.

However it seems strange that Serlio didn’t notice the weaknesses before the woodcutter ended the series of the plates. We can imagine that this was an unpleasant surprise for both of them. Perhaps the building site at Ancy-le-Franc, where he certainly was present for a long period as the quality of the Italian details testifies, didn’t allow enough time to guide the preparation of the plates which probably took place in Fontainebleau? Anyhow, such a mishap could hardly have happened at the end of his career, when he was free from other appointments. This is probably why he rightly pointed out in his letter dated 1552 that he had finished what he had promised in the Fourth Book, whereas he did not specify the technique by which the treatises would be printed: di haver dato fine al mio settimo libro cio è che la scrittura e tutta fatta: et le planse son tutte disegnate in peraro.42

The Avery manuscript at the starting point of Serlio’s late stylistic evolution

The comparison of Italian and French typologies inaugurated an entirely new method that Serlio adopted only for the humbler typologies. The fact that he didn’t apply this approach for all the other typologies makes the treatise seems incomplete and invites even to continue his work today! Such a distinction not only is much more difficult to deal with for the higher ranks of society, but its absence reveals also that Sebastiano himself was too much involved in these projects to adopt a theoretical framework. A large part of the Sixth Book’s drawings consists of variations of his own projects, where his guiding principle of reconciling French commodity and Italian style did not convincingly fit in. The treatise can only be partly considered as founded on rational principles; rather it consists of personal research on how to combine two different traditions. Within the framework of studies on migration and cross-pollination, the manuscript assumes a central role in the discipline of history of arts today, also providing new knowledge of the human capacity to assimilate to foreign models and techniques. For these reasons it is a highly revealing source, which requires further investigation. It is the watershed between Serlio’s Italian style, strongly anchored in High Renaissance idioms, and the attempts to assimilate French features, still strongly linked to late medieval traditions. The thirteen years spent in Venice enabled Sebastiano to combine Bramante’s and his school forms and principles with local peculiarities and to lay the foundation of his methods in France. But despite his Venetian experiences, at the court of Francis I he became a real architect confronted with very specific programs, which changed in a profound manner his methods and his vision of architecture.

Notes

1 On Serlio’s treatise see Sylvie Deswarte-Rosa, “Le traité d’architecture de Sebastiano Serlio. l’œuvre d’une vie” in Sebastiano Serlio à Lyon. Architecture et imprimerie, ed. Sylvie Deswarte-Rosa, Lyon: Mémoire Active, 2014, vol. 1, 30-63 ; see also Sabine Frommel, "Le traité de Sebastiano Serlio: œuvre d’une vie et chantier éditorial magistral du XVIè siècle" Histoire et civilisation du livre (IX, 2014) 101-127. See also William B. Dinsmoor, "The Literary Remains of Sebastiano Serlio," The Art Bulletin (XXIV, 1942), I, 55-91 and II, 115-154.

2 Sabine Frommel, Sebastiano Serlio architect (Milan: Electa/Phaidon Press, 2003), 61. English translation of Sabine Frommel, Sebastiano Serlio architetto (Milan: Electa, 1998).

3 Hubertus Günther, “Ein Entwurf Baldassarre Peruzzis für ein Architekturtraktat,” Römisches Jahrbuch für Kunstgeschichte (26, 1990), 135-170.

4 Mario Carpo, “Jean Martin, traducteur de Serlio, 1545-1547”, “Le Primo Libro par Jean Martin (Paris, Jean Barbé, 1545), edition bilingue”, “Le Secondo Libro traduit par Jean Martin (Paris, Jean Barbé, 1545), edition bilingue», in Sebastiano Serlio à Lyon. Architecture et Imprimerie, ed. Sylvie Deswarte, Lyon: Mémoire Active, 2004, vol. 1, 131-136; Anne-Marie Sankovitch, «Le Quinto Libro traduit par Jean Martin (Paris, Michel de Vascosan, 1547), édition bilingue, in Sebastiano Serlio à Lyon. Architecture et imprimerie, ed. Sylvie Deswarte, Lyon: Mémoire Active, vol. 1, 2004, 137-141; Francesco Paolo Fiore, «France: Books I-II, V, VI, VII and the “Extraordinario” in Sebastiano Serlio. L’Architettura. I libri I-VII e Extraordinario nelle prime edizioni, ed. Francesco Paolo Fiore, Milan: Edizioni Il Polifilo, 2001, vol. 1, 69-76.

5 Frommel, Sebastiano Serlio architect, 350-356.

6 Francesco P. Fiore, “Premessa” in Sebastiano Serlio, Architettura Civile. Libri Sesto, Settimo e Ottavo nei Manoscritti di Monaco e di Vienna, Milan: Il Polifilo, 1994, 3-26.

7 Frommel, Sebastiano Serlio architect, 83-216.

8 Françoise Boudon/Jean. Blécon, Le château de Fontainebleau de François Ier à Henri IV. Les bâtiments et leurs fonctions, Paris: Éditions Picard 1998, 50.

9 Sebastiano Serlio on domestic architecture (ms. Avery University, Columbia University), ed. Myra N. Rosenfeld (New York: The Architectural History Foundation, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: The MIT Press, 1978), f.1v.

10 Sabine Frommel, “De la casa del povero contadino à la casa del ricco cittadino: maisons rurales et maisons des champs dans le Sixième Livre de Sebastiano Serlio,” in Maisons des champs dans l’Europe de la Renaissance, ed. Monique Chatenet, Paris: Éditions Picard, 2006, 49-68.

11 The drawings on parchment held in the Staatsbibliothek in Munich Cod. Icon 189 has been published by Fiore, Architettura Civile. Libri Sesto, Settimo e Ottavo nei Manoscritti di Monaco e di Vienna, 43-246 e di Marco Rosci, Il trattato di architettura and Il sesto libro delle habitationi di tutti li gradi degli huomini, 2 vol. Milan: I.T.E.C, 1966. The printer proofs of woodcuts in the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek of Vienna in Sebastiano Serlio. I libri I-VII e Extraordinario nelle prime edizioni, ed. Francesco Paolo Fiore, vol. 2, 82-83.

12 Sebastiano Serlio on domestic architecture (ms. Avery University, Columbia University), ed. M. N. Rosenfeld, f.XI; Frommel, De la casa del povero contadino à la casa del ricco cittadino: maisons rurales et maisons des champs dans le Sixième Livre de Sebastiano Serlio, 58-61; Frommel, Sebastiano Serlio architect, 219-241; see recently Étienne Faisant, “Sebastiano Serlio à oeuvre; les consequences d’une revision de la chronologie du Grand Ferrare,” Quaderni dell’Istituto di Storia dell’Architettura, n.s., (63, 2014-2015),19-30.

13 Carpo, “Le Livre Extraordinaire (Lyon, Jean de Tournes, 1551), édition bilingue,” in Sebastiano Serlio à Lyon. Architecture et imprimerie, ed. Sylvie Deswarte-Rosa, Lyon: Mémoire Active, 2014, vol. 1, 144-146.

14 Archivio di Stato di Modena (A.S.Mo.), ADS (Archivio Ducale Segreto), Casa, Carteggio tra principi Estensi, letter from Hippolito d’Este to the duke, Argilly, 16-10-1546. Frommel, Sebastiano Serlio architect, 234.

15 A.S.Mo., ADS, Casa, Carteggio tra principi estensi, letter of the cardinal d’Este to the duke, Argilly, 16-10-1546. Frommel, Sebastiano Serlio architect, 222. When the cardinal d’Este left France, he inserted the project again on a sheet with a filigran of Lions. Francesco Paolo Fiore, “Le manuscrit du Sesto Libro conservé à Munich,” in Sebastiano Serlio à Lyon. Architecture et imprimerie, vol. 1, 167-168.

16 Frommel, Sebastiano Serlio architect, 103-124.

17 Later in Palladio’s emblematic villas since the 1550 the ideal will be materialized.

18 This clearly reveals the influence of north Italian Renaissance in particular that of Giulio Romano, Michele Sanmicheli and Falconetto who frequently used rusticated ground-floors and a piano nobile with arcades and blind-arcades.

19 Perché nel vero il padrone del palazzo qui a dietro dimostrato volse la fabrica in parte al suo modo per alcune sue comodità, mi è parso di formarne una come io la intendo, la quale non averà quelle commodità che ha l’altra, sarà almeno più osservata nelle difesse e meglio accompagnati gli appartamenti (ms of the Staatsbibliothek in Munich, 18v. Frommel, Sebastiano Serlio architect, 121.

20 Frommel, Sebastiano Serlio architect, 267-275.

21 By his master Peruzzi Serlio could have learned about such drawings. See Sabine Frommel, "Leonardo da Vinci und die Typologie des zentralisierten Wohnhaus," Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz (2006 3), 257-300; Sabine Frommel, “Ricerca, immaginazione, malinteso: Francesco di Giorgio e la tipologia degli edifici residenziali a pianta centrale,” in Francesco di Giorgio alla corte di Federico di Montefeltro, ed. Francesco P. Fiore, (Firenze: Olschki, 2004), vol. 2, 643-677; Sabine Frommel, “Sogni architettonici: i Sangallo e la tipologia di palazzi e ville a pianta centralizzata,” in Quaderni dell’Istituto di Storia dell’Architettura (40, 2002) 17-38.

22 Sabine Fommel, “Residenze a confronto: Il palazzo di Carlo V a Granada, il castello di Fontainebleau e la ricostruzione del Louvre di Francesco I,” ed. Sabine Frommel e Pedro Antonio Galera, El patio circular en la Arquitectura del Renacimiento. De la Casa de Mantegna al Palacio de Carlos V (Sevilla: Servicio de Publicaciones UNIA, Universidad internacional de Andalucía, 2018), 215.

23 The walls are carved by niches and recall Giuliano da Sangallo’s famous project of the residence of the king of Naples from 1488.

24 Sabine Frommel, “Sebastiano Serlios ‘padiglione al costume di Franza’ in Fontainebleau,” Höfische Bäder in der Frühen Neuzeit. Gestalt und Funktion, ed. Kristina Deutsch, Claudia Echinger-Maurach, Eva-Bettina Krems (Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter), 2017), 78-84.

25 A.S.Mo., CAF (Carteggio degli ambasciatori di Francia), b.XXVIII, letter of the ambassador Alvarotti to the duke d’Este, 5-3-1546, Frommel, Sebastiano Serlio architect, 91, 356.

26 A.S.Mo., ADS, Carteggio tra principi Estensi, letter from the cardinal Hippolito d’Este to the duke of the 16-10-1546. Frommel, Sebastiano Serlio architect, 225, 356).

27 Frommel, Sebastiano Serlio architect, 356.

28 Fiore, “Les épreuves d’imprimerie du Sesto Libro conserves à Vienne» in Sebastiano Serlio à Lyon. Architecture et imprimerie,” 171.

29 Cf. note 11. Fiore, “The manuscript du Sesto Libro conserve à Munich» in Sebastiano Serlio à Lyon. Architecture et imprimerie,” 167-170; Frommel, Sebastiano Serlio architect, 356.

30 Sebastiano Serlio. I libri I-VII e Extraordinario nelle prime edizioni, ed. Fiore, 28-31, Julian Jachmann, Von Serlio bis Ledoux: Differenz und Wiederholung in seriellen Publikationen zur französischen Wohn-und Residenzarchitektur Köln: Kölner Architekturstudien, 2016, vol. 1, 42-43

31 Frommel, Sebastiano Serlio architect, 355-356.

32 The correction of the proportion regards also the façade (f.53r) - one of the few cases where the monumental central motif had been replaced by three dormer windows.

33 In this case Serlio renounce on the rusticated elements of the versions of the Avery manuscript and the woodcuts.

34 Sebastiano Serlio. I libri I-VII e Extraordinario nelle prime edizioni, Fiore, 28-31, Julian Jachmann, Von Serlio bis Ledoux: Differenz und Wiederholung in seriellen Publikationen zur französischen Wohn-und Residenzarchitektur, 42-43.

35 Fiore, “Les épreuves d’imprimerie du Sesto Libro conserves à Vienne » in Sebastiano Serlio à Lyon. Architecture et imprimerie,” 173.

36 Annie Charon-Parent, “Serlio et ses imprimeurs parisiens,” Sebastiano Serlio à Lyon. Architecture et imprimerie, vol. 1, 119.

37 David.Thomson, Renaissance Paris. Architectuure and Growth, 1475-1600, London: A.Zwemmer LTD, 18 (Plate 1-6, 8, 13 and 14). In his treatise Temples et logis, c.1545, he copied and modified several drawings from this manuscript and it seems that thanks to these exercise he became a specialist in architecture Sabine Frommel, “Jacques Androuet du Cerceau et Sebastiano Serlio: une rencontre désisive,” in Jacques Androuet du Cerceau “un des plus grands architectes qui ne soient jamais trouvés en France”, ed. Jean Guillaume with the collaboration of Peter Fuhring (Paris: Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine, 2010), 123-129.

38 Jean Guillaume, “Qui est Jacques Androuet du Cerceau”, ibid., 17. Already in 1545 he obtained from Francis I a copyright for publication of prints of ornaments. Serlio will use the copperplate technique for Libro Straordinario (Lyon 1551).

39 See the plates 16v and 23v of the Fifth Book.

40 Sebastiano Serlio, Della sesta habitazione alla villa, p. 12 (Sebastiano Serlio. I libri I-VII e Extraordinario nelle prime edizioni, Fiore).

41 Carpo, “Le Livre Extraordinaire (Lyon, Jean de Tournes, 1551), édition bilingue,” 145-146.

42 Letter from Sebastiano Serlio to François de Dinteville (BNF, Paris, Collection Dupuy, ms. 728, f.178r/v of the 19th May 1552); Frommel, Sebastiano Serlio architect, 36-38; Fiore, “Les épreuves d’imprimerie du Sesto Libro conserves à Vienne,” in Sebastiano Serlio à Lyon. Architecture et imprimerie, ed. Sylvie Deswarte-Rosa, Lyon: Mémoire Active, 2014, vol. 1, 171.