Galletti Essay

SARA GALLETTI, Duke University, Paired Models: Comparing Domestic Typologies Between Italy and France

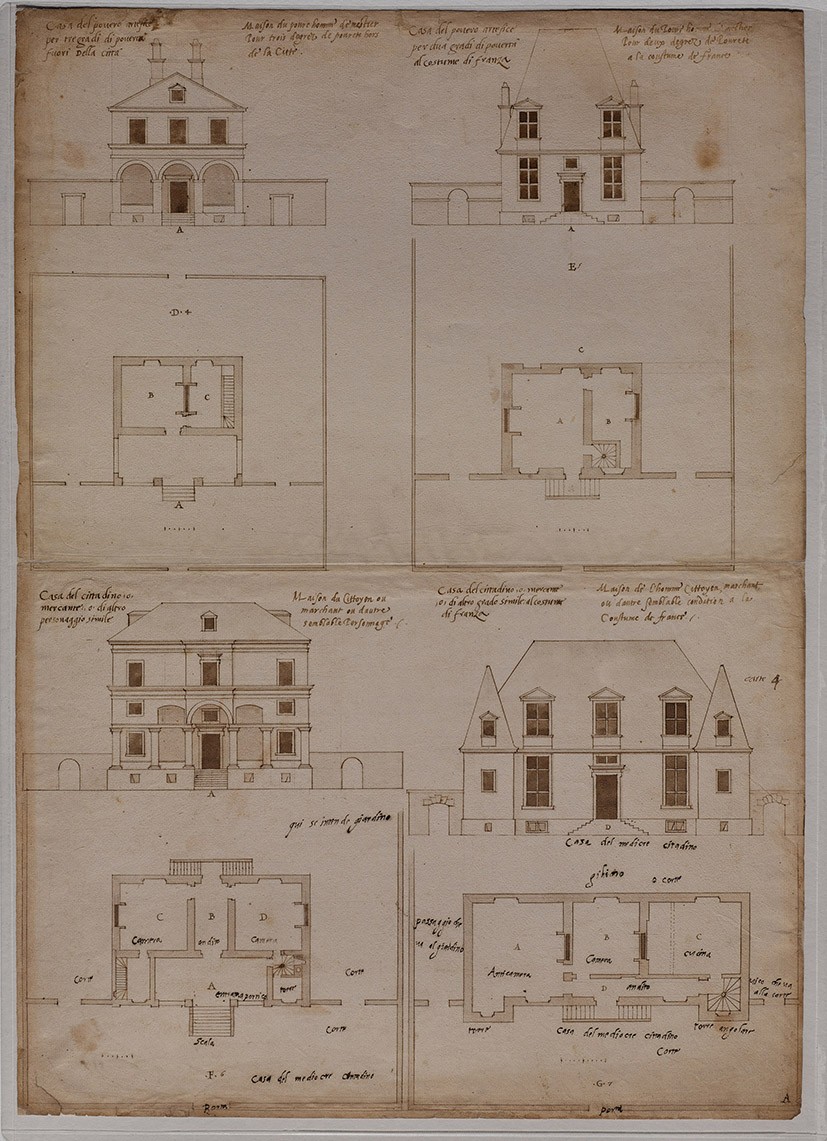

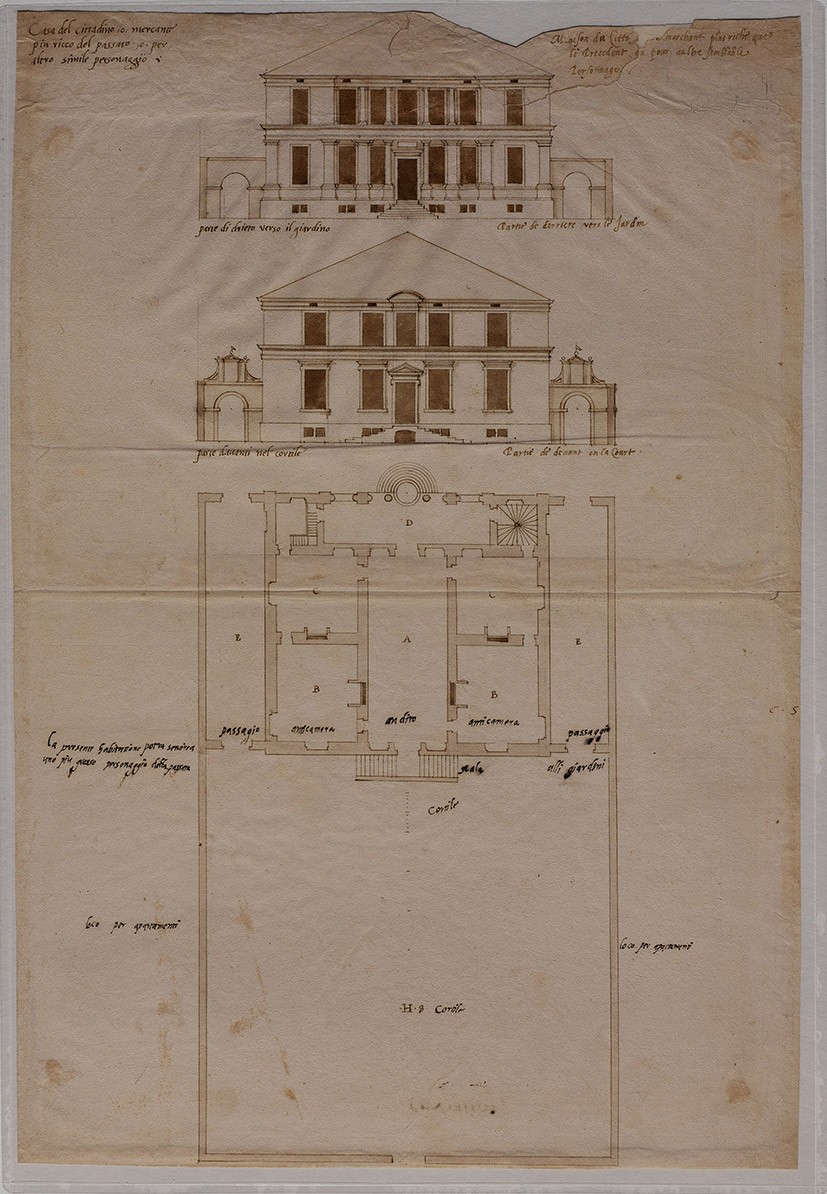

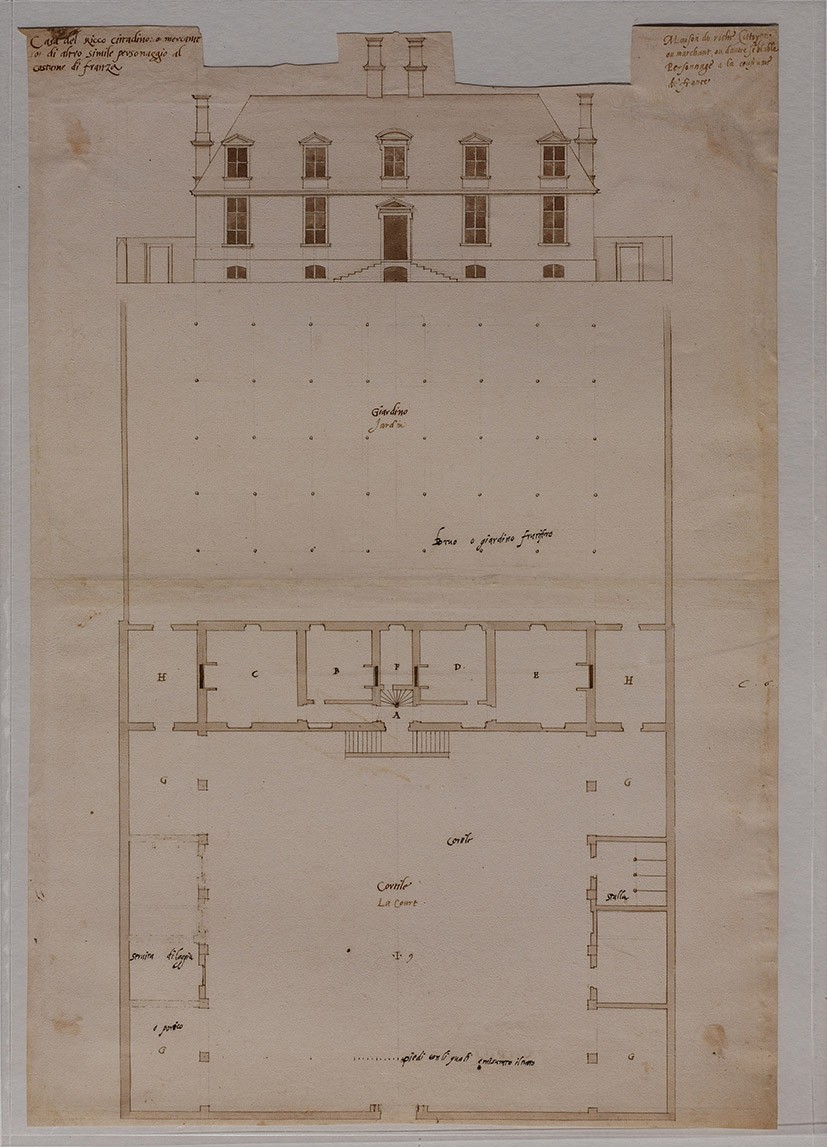

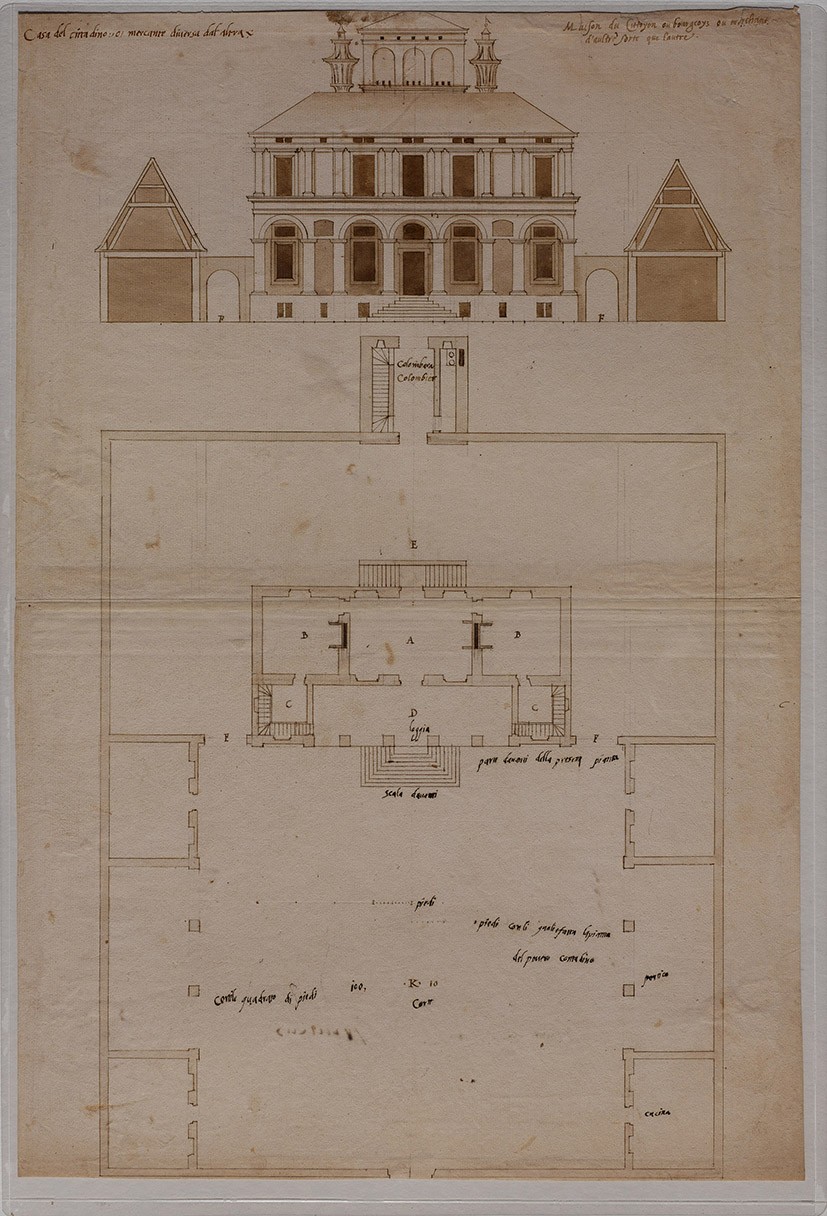

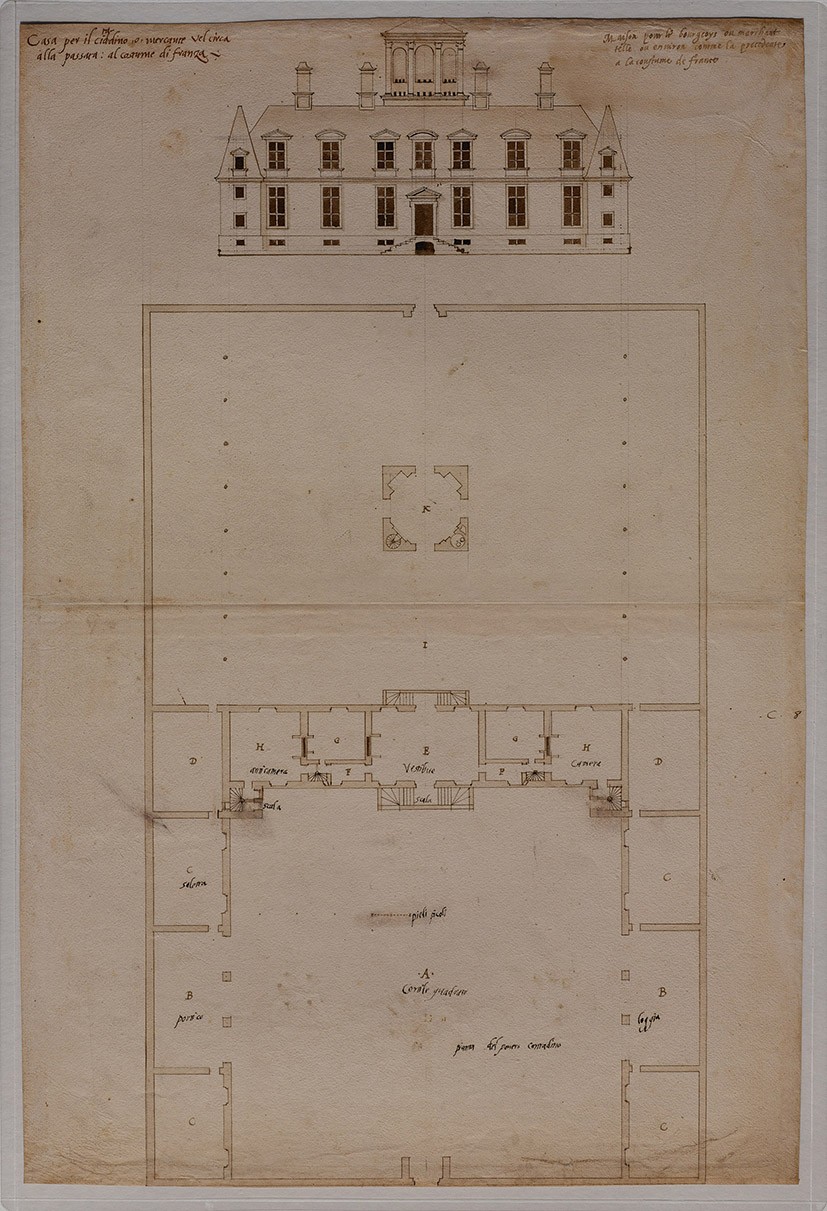

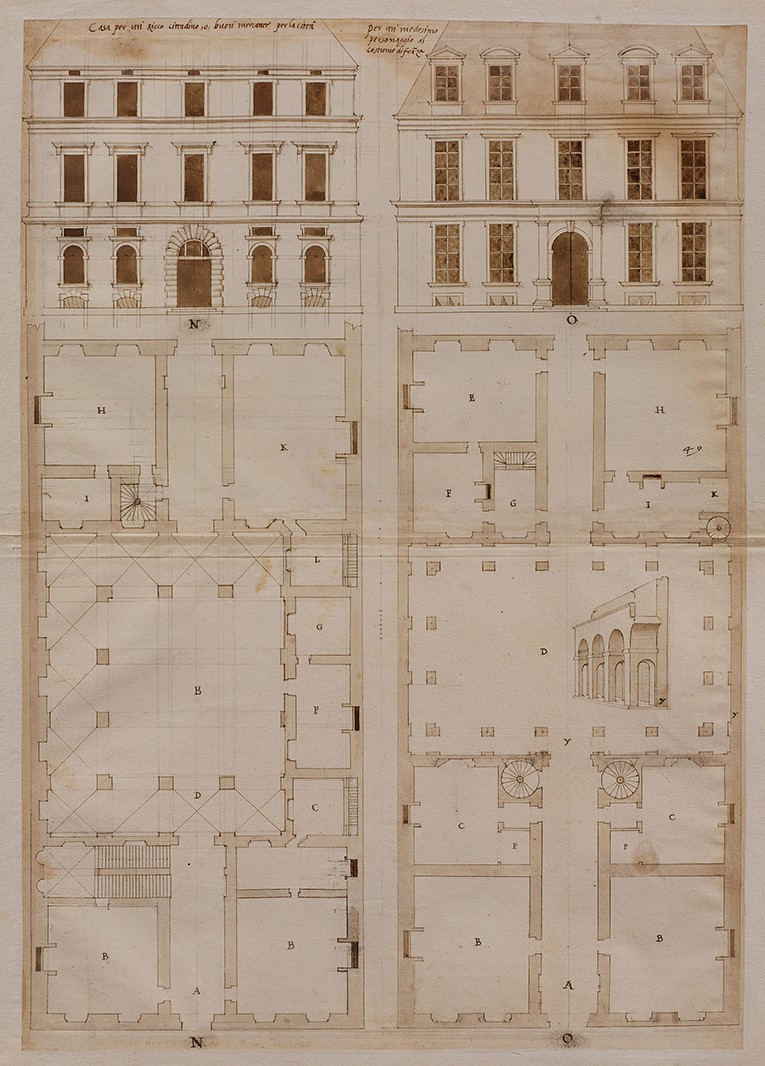

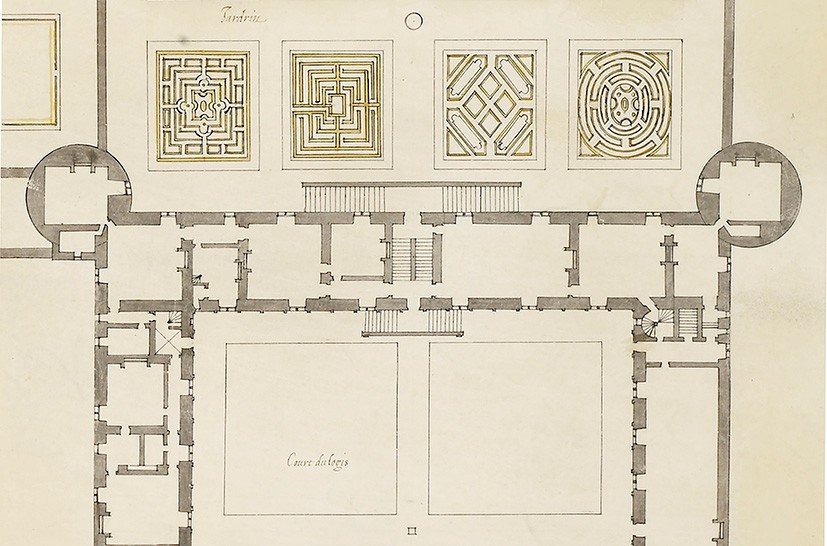

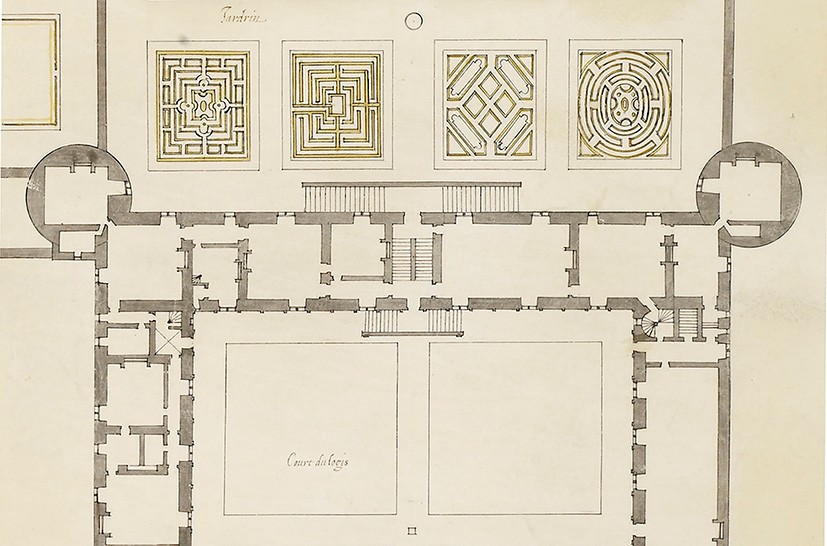

Of the 53 projects Serlio includes in the Avery version of his manuscript On Domestic Architecture, 18 are paired Italian and French versions of the same house (D4–L11 and E-O, pl. II–VI and XLVIII–LI, Fig. 1–9). Whereas the majority of the projects in Book VI are hybrids that freely combine architectural elements of different origins, including Roman, Bolognese, Paduan, Venetian, Parisian, and Bellifontain, in the paired models Serlio isolates and emphasizes the distinctions between the architectural features that characterize two separate geographical, social, and cultural environments. Thus, the paired models offer a unique insight into Serlio’s experience of France and his understanding of architecture as a context-bound practice.

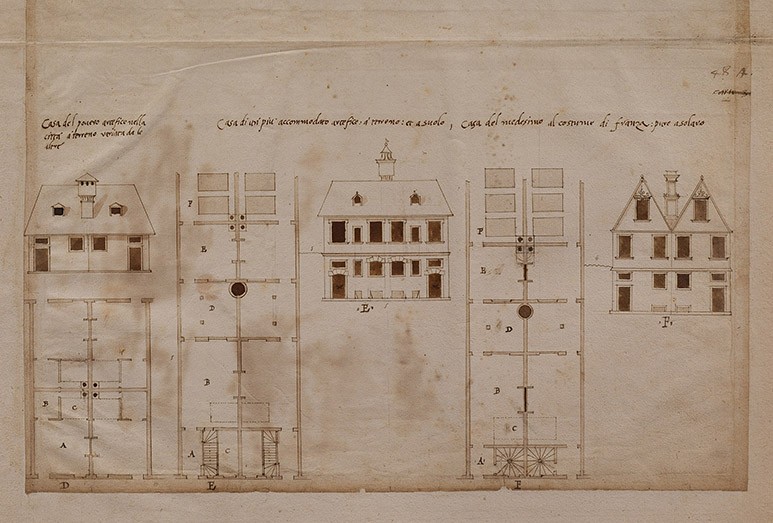

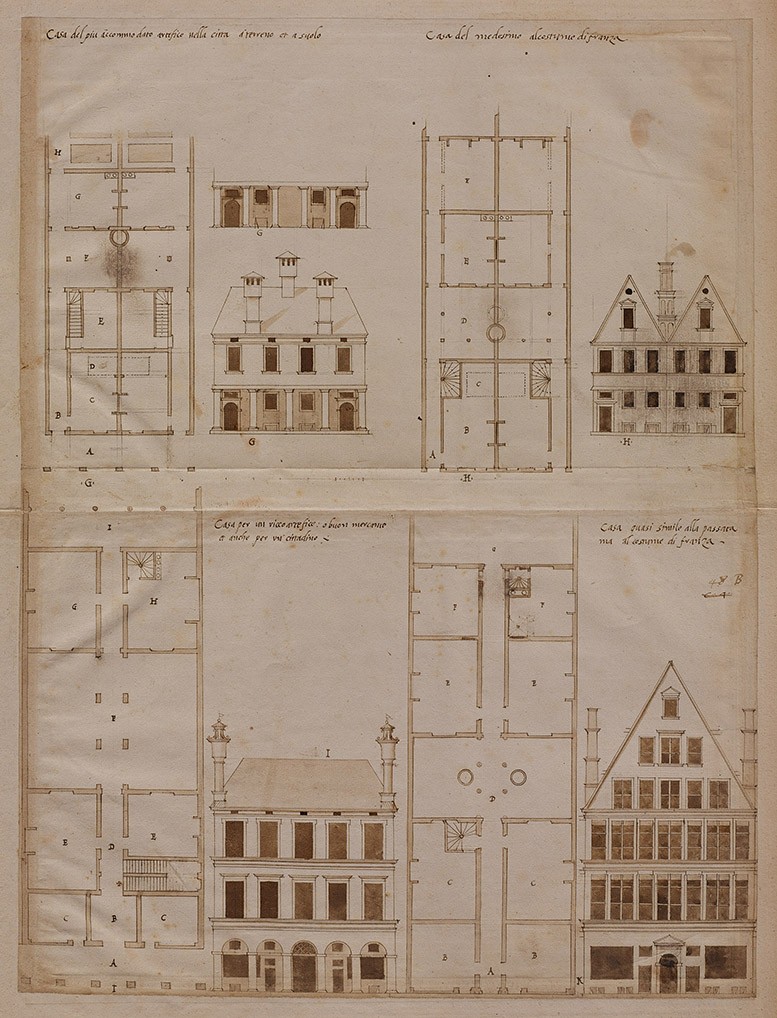

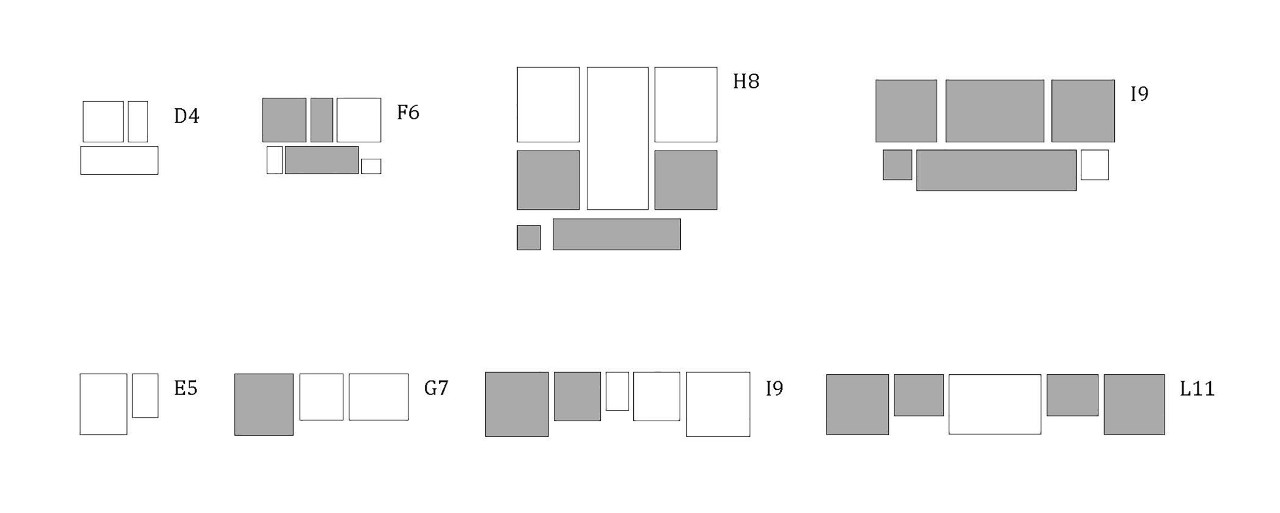

Eight of the paired models are for country houses (D4–L11) and ten are for city dwellings (E-O). In both categories, the house types are ordered according to the ascending social rank and financial means of their residents, from poor artisans to rich citizens and merchants. Each category privileges one group over the other: among country houses, only two models target artisans (D4 and E5) but six target citizens and merchants (F6–L11); among city dwellings, six models target artisans (E–K) but only four target citizens and merchants (L–O). Half of the models contain multiple variants based on need and financial possibilities—for example, the text accompanying model D4 specifies that it illustrates four possible houses: the two-story house with two rooms and a loggia on the ground floor shown in the drawing; a one-story version of the same; a one-story, two-room (B and C) house with no loggia; and a one-story, one-room (B) only house (Fig. 1). These variants introduce a high degree of flexibility in the model structure adopted by Serlio, thus allowing him to address the granular needs of a broad potential clientele.

In addressing the housing needs of the poor, artisans, and merchant classes, Serlio’s paired models reflect some of the most relevant socio-economic phenomena of his time.1 The merchant class grew larger and more powerful during the fifteenth and sixteenth century in both the Veneto and in France, where new laws allowed noblemen to engage in commercial enterprises, on the one hand, and, on the other, urban merchant families were granted access to nobility. These changes promoted a new need for both urban and countryside upper-scale residences for the “richer citizens or merchants” that Serlio addresses in models H8–L11 and N-O. On the opposite end of the socio-economic spectrum, Serlio’s countryside models for both “poor” and “better-off artisans” (D4–G7) reflect a preoccupation with the combined pressures of demographic growth and economic depression that pushed many urban dwellers out to the countryside as well as with initiatives that encouraged the transfer of economic investments from urban sites into farmland ones. The largest category of Serlio’s paired models addresses the middles classes of artisans (E–H) and “good merchants” (I–M) whose dwellings, while rarely at the center of theoreticians’ attention, are in the largest numbers and make up a city’s fabric. While the issue of middle-class urban housing had been touched upon by Dürer and Filarete already, Serlio is the first theoretician to provide actual models for such dwellings.

The paired models range in size from the smallest variant of country house D4 for the poor artisan, a one-room 169-square-foot cottage, to the largest urban house O for a French rich citizen/merchant, which sits on a plot just shy of 8500 square feet. The models’ sizes grow progressively across each category of country or urban dwellings, with the sole exception of house H8, which is larger than the following I9, K10, and L11. The Italian and French versions of each paired model are approximately the same size across the two categories, with the sole exception, again, of house H8, the plan of which is twice as large as that of its French counterpart, I9.

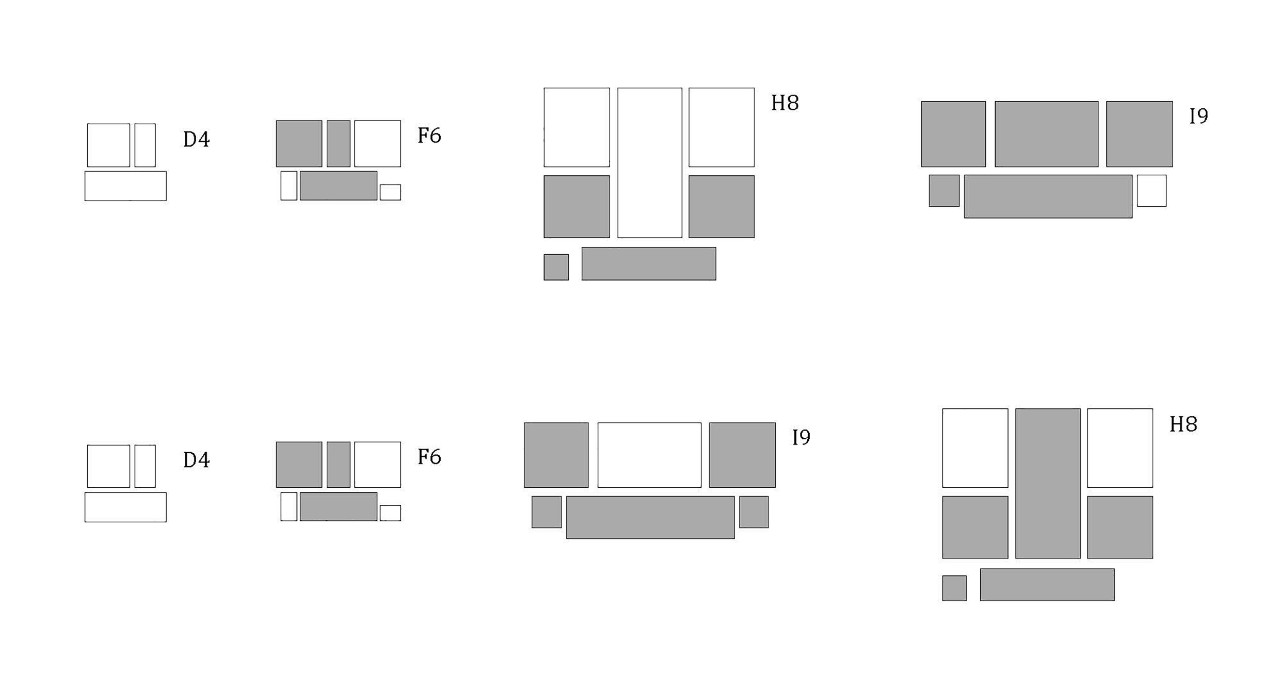

The progression in size from one model to the next is realized through the addition of new and larger rooms, but it follows different geometric criteria in the categories of country houses and city dwellings. For the country houses, Serlio keeps the series of French and Italian models separate from each other by adopting two distinct patterns of growth: linear for the French houses; clustered around a central space for the Italian ones (Fig. 10). The French houses thus maintain the one-room deep corps de logis that Serlio identifies as a distinguishing feature of French architecture, whereas the Italian houses evoke the plans adopted already in fifteenth-century Medici villas. It is worth noticing that house H8 seems, again, out of place when examining the progressive pattern of growth of the Italian models. As shown in Fig. 11, if house H8 came after house K10 instead of before, the series would show a more progressive pattern of growth than it does in Serlio’s original arrangement. Swapping places with K10 would correctly place H8 at the end of the series as the largest of the Italian models, and it would also correctly pair it with the largest of the French models, L11. The fact that the closest variant to house H8 contained in the Vienna printer’s proofs is, indeed, paired with L11, may be an indication that Serlio misplaced house H8 in the Avery manuscript’s sequence (Fig. 12).

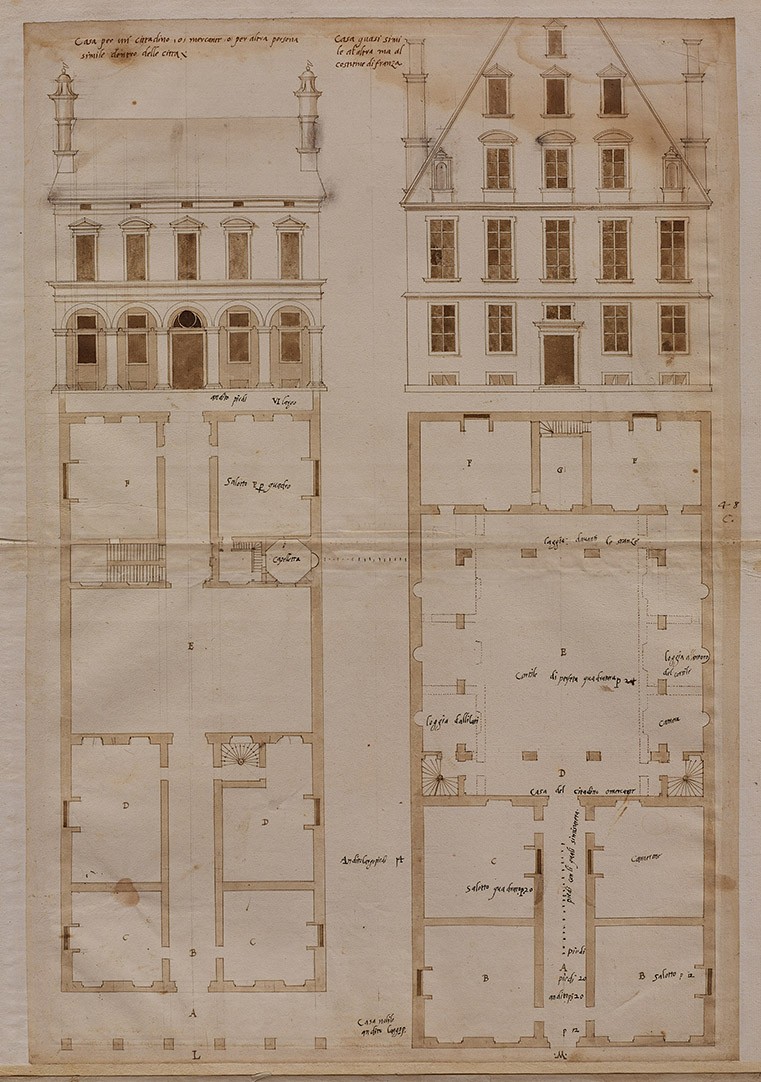

In the category of city dwellings there are no marked differences between the French and the Italian series in what concerns patterns of growth from one model to the next (Fig. 13). Differences are instead recognizable here among two models’ subgroups: apartment houses and palazzetti on the one hand (E–K), palazzi and hôtels particuliers on the other (L–O). The apartment houses grow following a linear pattern in models E to H and they double along an axis of symmetry in models I and K. The larger residences, L to O, follow instead a more complex pattern of growth based on the progressive clustering of rooms into residential units, logis and appartamenti, gravitating around the central courtyard.

From the point of view of typology, Serlio differentiates the French models by introducing a large-scale apartment house that finds no correspondent among the Italian ones. While it is clear from the description of its interior distribution that house I is a palazzetto, designed for a single household, in describing its French correspondent, house K, Serlio states that the kitchen F, at the back of the building, is replicated at the upper floor, thus indicating that multiple households would occupy the building (Fig. 7).2 However, it is unclear how the vertical distribution would function in such setting, as the location of the main staircase, in room C, does not allow for a simple horizontal separation of different apartments. In the Munich manuscript, Serlio abandons the idea of multiple apartments for house K (X in the Munich MS), which he presents a single-household palazzetto like its Italian counterpart I (IX in the Munich MS).

Serlio demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of French distribution practices. In models F and H, he illustrates a typical French setting for the bed, between the fireplace and the wall, which he extends to the Italian models E and G.3 Model G7 shows the ideal interior setting for a typical French bedroom, with the space for the bed comprised between the fireplace and the exterior wall, away from the entrance, and, in the corner opposite the bed, a recess where to place a second, small bed (piccolo lettoor, in the Munich manuscript, lettuzzo) which was traditionally used as a sofa during the day (Fig. 1). A door next to the fireplace leads to a second, smaller room that has the function of a guardaroba “as they call it here,” a storage room traditionally associated, in France, with the bedroom and which Serlio translates as retrocamera in the Munich manuscript. The same association of bedroom and guardaroba as the smallest unit of a French logis is repeated in models I9 (rooms C and B), L11 (rooms H and G), M (rooms F and G), and O (rooms F and G and H and I).

In models E5 and G7, Serlio provides two alternative solutions to a problem French architects of his time incurred frequently: the distribution of windows that had to satisfy the often-diverging requirements dictated, on the one hand, by the interior distribution of the bedroom’s furnishings and, on the other hand, by the desire to impose regularity, if not always symmetry, to the façades of buildings (Fig. 1). In model E5, Serlio uses a blind window to allow for the positioning of the bed in the upper left corner of room A while maintaining the symmetry of the façade to the back of the house. In model G7, instead, he chooses to space the openings of the façade on the garden in a way that allows for the bed to fit in the upper right corner of the room A. In both cases, the bedroom window is off-centered on the interior wall, a characteristic that does not apply to the Italian versions of the same models, D4 and F6.

Serlio also differentiates systems of vertical distribution in the paired models. For the external stairs leading to the entrance of country houses, he employs a variety of shapes for the Italian models—straight, round, pyramidal, and converging—whereas he only uses converging ones for the French models. Similarly, the Italian urban models feature straight, half-pace, and spiral interior staircases, while the vast majority of the French models only feature spiral ones.

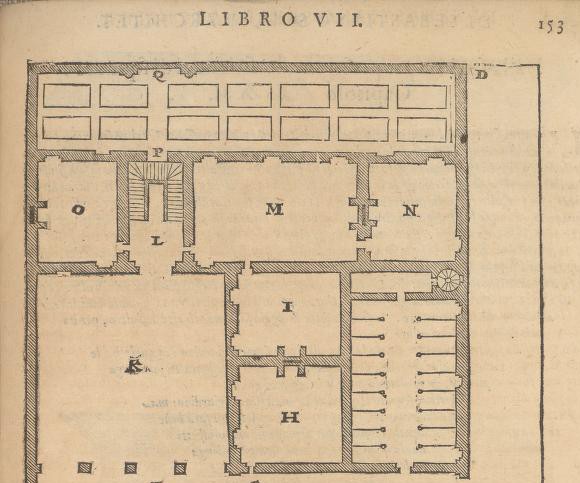

In house I9, Serlio tries his hand at a second staple of French interior distribution: the unit composed by entrance, staircase, and passage to the garden which had fascinated French architects at least since the building of Bury (Fig. 14). The solution proposed in house I9 is far from satisfactory because such a prominent position for a staircase that only serves the galetas (the rooms located under the roof) is unjustified, and because room F does not actually provide access to the garden, and thus becomes a rather redundant camerino cut off from the plan’s distribution. Yet, Serlio’s interest in this theme will lead him to other, more successful solutions—for instance in the Settima proposizione de’ siti fuori di squadro of Book VII (Fig. 15)—which will prove crucially important for later developments in French architecture, including in the Luxembourg Palace.4

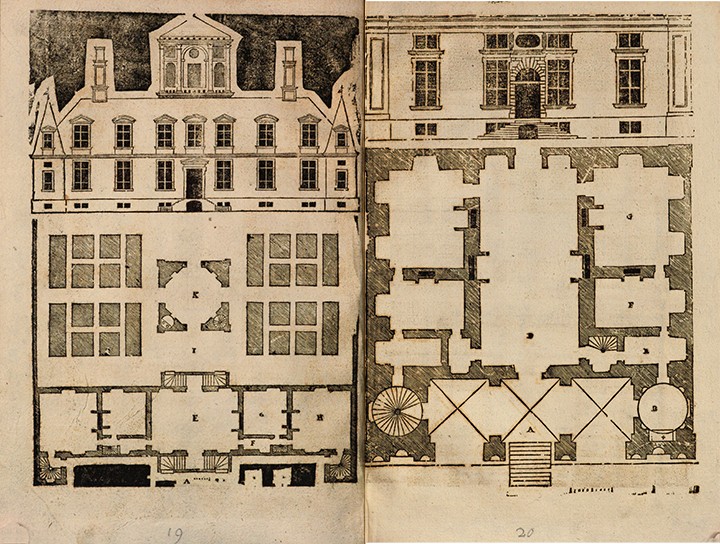

It is in the elevations that the paired models show the broadest range of differences between Italy and France. While the models are not devoid of common traits—for instance, in the use of tall, Venetian-like chimneys as well as of a few dormer windows in the Italian houses—Serlio identifies a variety of features that markedly distinguish Italian façades from their French counterparts in the arrangement of volumes, the shape of roofs, the distribution of stories, the rhythmic articulation of facades, and in the use of architectural orders.

Serlio’s French houses, in both the country and city categories, showcase tall, pitched profiles justified by the presence of galetas, rooms and apartments located under ample roofs. In order to provide appropriate lighting to these rooms and apartments, the French urban models are front-gabled and the countryside ones feature numerous large dormer windows. The presence of galetas also projects the hierarchy of the interiors directly onto the façades of the French models—for the main apartments are never under the roof—a hierarchy which in the Italian models is more subtly expressed by the difference in the height of the stories and/or the use of architectural orders. The pair H8–I9 is a case in point (Fig. 2 and 3). Country houses G7 and L11 also showcase the projecting corner volumes topped by individual roofs that characterize the profiles of so many French buildings in Serlio’s time (Fig. 1 and 5).

On the facades of most French models, Serlio features tall cross-windows which he appreciates “because they are divided crosswise, [so that] it is possible to regulate the light at will because every square of the cross may be closed separately” (f. 88ar). In the country houses, these windows are connected to the roof dormers to form vertical features that provide rhythm to facades that are otherwise plain when compared to their Italian counterparts, which are enlivened by the presence of loggias, architectural orders, and the rhythmic distribution of openings.

Architectural orders are prominent in the Italian models, including in modest country houses such as F6, whereas they are mostly absent from the French one—the only exceptions being the dovecote marked K in house L11 and the entrance portal in house O (Fig. 5 and 9). The bareness of Serlio’s French façades counters the interest in the classical orders and, more generally, in classicizing decorative vocabulary that characterizes French architecture of the 1540s. Perhaps, the choice reflects the architect’s preoccupation that such classicizing vocabulary may have looked foreign still to the middle-class patrons he addresses with the paired models.

Serlio’s paired models are neither utopian nor unprecedented. Rather, they are responses to the housing needs of his time based on existing practices that the architect translates into schemes that have the ambition to be, at once, universal and characterized with regard to their geographical, social, and cultural contexts.5 Such translations are not always successful, in particular when they involve French practices that Serlio seems to misunderstand.6 The most blatant of such misunderstandings concerns the hôtel particulier, the French urban residence characterized by a corps-de-logis that is set back from the street and preceded by a walled courtyard, in a plan arrangement that reminds one of a countryside château. The hôtel particulier is the French equivalent of the Italian palazzetto and palazzo, and it is thus surprising to not find it featured in the paired models L-M and N-O, where Serlio chooses instead to illustrate Italianate houses that find no precedent in French practice (Fig. 8 and 9). Similarly, the tall front gable of house M has no correspondent in the French tradition, and rather recalls Flemish and other northern and central European urban landscapes. These misconstructions of architectural Frenchness betray the difficulties presented by Serlio’s ambitious program for Book VI, that of defining an international architectural style inspired by ancient models but capable of adapting to local habits, taste, needs, and resources.

1 On this topic, see in particular Myra N. Rosenfeld, Sebastiano Serlio on Domestic Architecture: Different Dwellings from the Meanest Hovel to the Most Ornate Palace: The Sixteenth-Century Manuscript of Book VI in the Avery Library of Columbia University (New York: Architectural History Foundation, 1978), 41–49.

2 “Questa servirà di cucina, e da basso et da alto,” Avery MS f. 69ar.

3 On this topic, see in particular Monique Chatenet, “‘Cherchez le lit’: La place du lit dans la demeure française au XVIe siècle,” ed. Aurora Scotti Tosini, Aspetti dell’abitare in Italia tra XV e XVI secolo. Distribuzione, funzioni, impianti (Milan: Edizione Unicopli, 2001), 145–53. One should keep in mind that the room functions indicated on the drawing themselves, and which are often at odds with Serlio’s descriptions in the text, are not the author’s (see William B. Dinsmoor, “The Literary Remains of Sebastiano Serlio,” The Art Bulletin (24, 1942), 115–54, in particular 123–24, and Rosenfeld, Sebastiano Serlio on Domestic Architecture, 29.

4 On the influence of Serlio’s models on the design of the entrance to the corps de logis of the Luxembourg Palace, which also combines access to the garden and to the main staircase, see Sara Galletti, Le palais du Luxembourg de Marie de Médicis, (1611-1631) (Paris: Picard, 2012), 184–93.

5 On the real-life models of Serlio’s projects, see in particular Rosenfeld, Sebastiano Serlio on Domestic Architecture, 71–75; Sabine Frommel, “De la ‘casa del povero contadino’ à la ‘casa del ricco Cittadino’: maisons rurales et maisons des champs dans le Sixième Livre de Sebastiano Serlio,” ed. Monique Chatenet, Maisons des champs dans l'Europe de la Renaissance: actes des premières Rencontres d'Architecture Européenne, Château de Maisons, 10-13 juin 2003 (Paris: Picard, 2006), 49–68.

6 See Jean Guillaume, “Serlio et l’architecture française,” ed. Christof Thoenes, Sebastiano Serlio: Sesto Seminario internazionale di storia dell’architettura, Vicenza 31 agosto–4 settembre 1987 (Milan: Electa, 1989), 67-78.